By Claire Haskell

On Isabelle Haskell De Tomaso's 21st birthday in 1951, her father gave her $2000 to purchase her first car. Instead of spending the money at her cousin's local automotive dealership, she traveled two hours away to purchase an MG-TD. The sports car's open-air design, spirited engine, and finely-crafted framework presented the perfect opportunity for Isabelle to indulge.

She may not have always done what was expected of her, but at least she had exceptional taste in cars.

After watching her emerge from her newly acquired MG-TD, her father, Amory Haskell, quickly learned she did not go for the understated Chevrolet like he presumed she would. Neither of them knew it at the time, but this marked the beginning of Isabelle's unbreakable bond with cutting-edge sports cars. Only next time, it would manifest itself on a racetrack rather than a driveway.

Hearing my Great Aunt Isabelle recount her memories made me want to go back in time and experience them firsthand. I wanted to watch her appear on the driveway in her first sports car, drive on a race track for the first time, win a race, or even lose some. However, my visit to her home in Palm Beach, FL, served as the perfect alternative.

Her one-story white house sits on a scenic, tranquil street, where the ocean is close enough to hear and the air humid enough to feel on my skin. The home's true character lies within it, where it remains entirely uninterrupted by the swift speed of time. Filled to the brim with framed pictures, dusty photo albums, treasured books, and delicate antiques, its interior takes me back to the day Isabelle bought it in 1986.

Sitting together in her living room, I become surrounded by memories, her memories, ones that still replay in her mind as if they were yesterday. It feels like a warm blanket of nostalgia, temporarily wrapped around us as we share the space. After she settles in her favorite reclining chair by the window, we begin to unravel her story in bits and pieces.

Isabelle wasn't the only member of her family that was passionate about cars. Her father was a former General Motors executive and the founder of Triplex Automotive Glass. While they shared an interest in the automobile industry, they had different expectations for Isabelle's future.

Brought on by her father's successful business endeavors, the family was deeply involved in high society life present in both Middletown, New Jersey, and Palm Beach, Florida; this meant attending fancy dinners and frequent cocktail hours, activities that Isabelle was not eager to partake in. Although being a part of this lifestyle was the standard in her family, Isabelle gravitated towards the unconventional route.

Isabelle at her First Race

Instead of attending college, she began working at the Radiation Research Corporation of West Palm Beach, a small company that specialized in the study of nuclear batteries. Conveniently for Isabelle, the corporation's founders were major car enthusiasts who loved to race on weekends. One day at work in February of 1953, Isabelle agreed to accompany them to a race in Tampa, FL.

Unsurprisingly, Isabelle didn't derive much interest from merely observing the race; her inclination was to participate instead. To achieve this, she took a test with an automobile club member to obtain a special license. "We got in the car, and he said, 'I'm terrified. Please just go slow, and I'll give you the okay,'" she recalled.

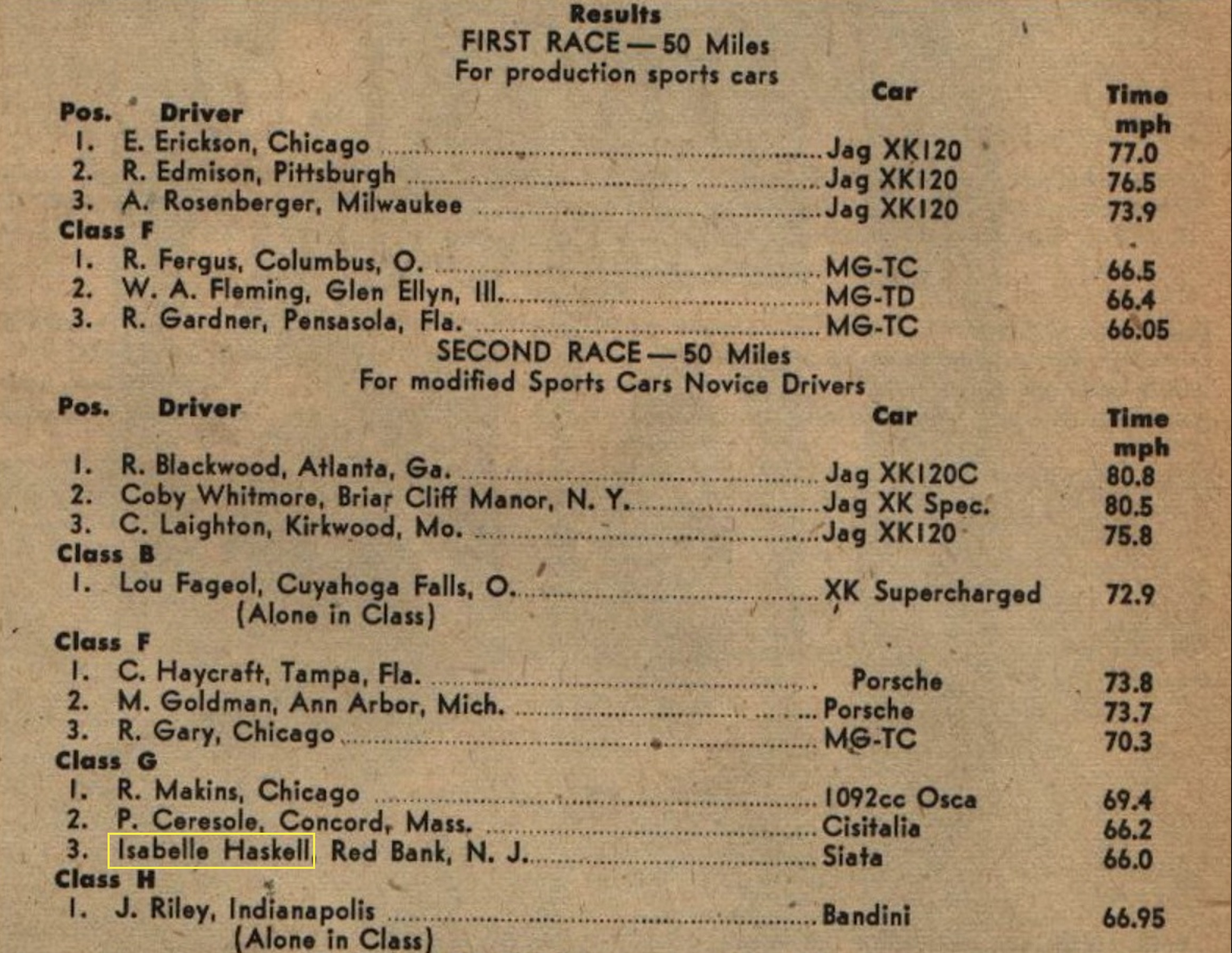

That same day, she participated in her first race: the SCCA National Macdill at the Tampa Air Force Base. As the 50-mile competition unfolded, a crowd of 90,000 people watched intently as Isabelle carefully maneuvered her sleek, aerodynamic sports car around the track. As if obtaining her license and competing in her first race wasn't enough for one day, Isabelle finished third in her class.

"I wasn't scared," she told me. "I was going over 100 miles per hour. I didn't have time to be scared."

First Race Results

Following her success, it all cliqued for Isabelle. Her far-fetched dream to race cars suddenly transformed into a realistic possibility, but acting on this passion meant going against her father's wishes. Nonetheless, her father knew nothing could hinder Isabelle from pursuing her ambitions.

"My father said to me, 'I don't like racing. That makes me nervous in every way. But if you're good at it, keep at it. If you aren't, quit,'" With that, Isabelle set out to prove just how good she could be.

In 1953, she raced around the United States with her brother Amory and his wife Helen, participating in the SCCA National Bridgehampton in New York, SCCA National Lockbourne in Ohio, and the SCCA National in Connecticut. However, the racing opportunities for women in the states were limited at the time, as authorities were conservative about allowing men and women to compete in the same races.

On a phone call with Isabelle's niece and nephew, Isobel and William Ellis, Isobel explained that the United States had "what they call powder puff races where there were basically women who, at least in the beginning, weren't taking it all that seriously. So she refused to go into those races."

In Europe, however, there was a more liberal approach to racing. Not only could they compete against each other, but women were also were paid to start. "It was a crowd drawer; that's why they gave women more money," Isabelle explains.

Throughout 1954, Isabelle continued participating in races in her Siata 300BC, one of only 50 models ever produced. Her most notable race this year was her second time at the SCCA National Thompson in Connecticut, where she placed 2nd in the women's division. At this point in Isabelle's career, she was beginning to garner admiration from the public.

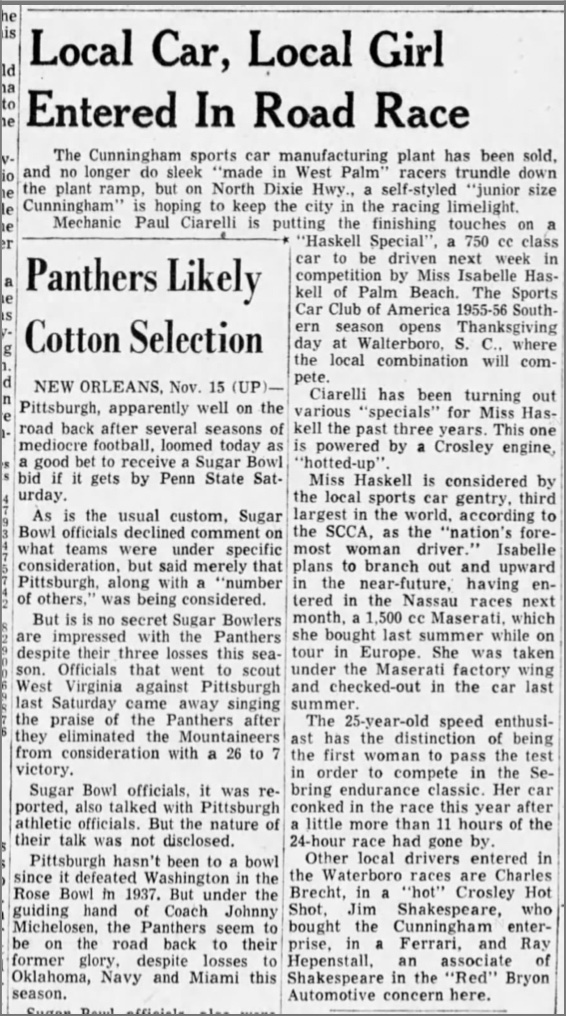

According to The Palm Beach Post in 1955, the SCCA had now considered her "the nation's foremost woman driver." Mechanic Paul Ciarelli had even made Isabelle her own car called the "Haskell Special," which was to be driven in the SCCA Walterboro race in November. Ciarelli had been making her various specials for three years before this race.

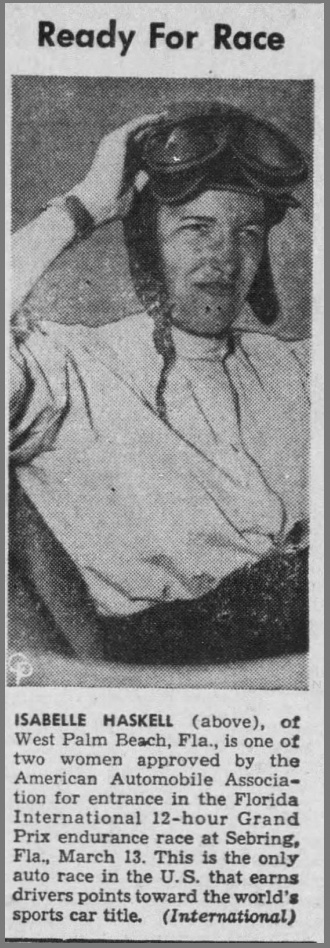

"The 25-year-old speed enthusiast has the distinction of being the first woman to pass the test in order to compete in the Sebring endurance classic," The Palm Beach Post wrote. In March of 1955, Isabelle managed to affirm this speculation.

Only four years after Isabelle snuck off to purchase an MG-TD for her 21st birthday, she was already breaking world records for racing, let alone pioneering an entire movement. She proved to the world that women were perfectly capable of not only participating in races against men, but also winning against them.

Isabelle's public recognition never fazed her, though. She raced simply for the love of it, and her undeniable longing for competition. When I attempt to applaud her for her accomplishments, she responds with a simple but telling, "I just wanted to win."

Despite Isabelle's modesty, she was a difficult one to overlook. Her charming smile, golden blonde hair, and 5'10" height were a constant draw.

"People had an emotional attachment to her. They said she was beautiful to watch drive, she was beautiful to watch get into the car, and she was beautiful to watch get out of the car," her niece shares.

"Of course, if you said that to her, she would say that's not true, and they needed glasses," she quickly added in illustration of Isabelle's unquestionably humble nature.

It's not surprising that Isabelle's character was just as infatuating as her appearance. When people met her, they couldn't help but want her around. Her carefree spirit and sharp wit made her easy to love and difficult to forget. "She had opinions, and she was brash," explains Isobel.

In December, Isabelle traveled to the Bahamas with her new Maserati 150s to race at the prestigious Nassau Speed Week alongside multiple renowned racers, like Mike Hawthorn and Stirling Moss. Instead of entering the ladies' race, she competed in the main division against men and came 16th in the Governor's Trophy and 21st in the Nassau Trophy. Around this time, Isabelle also worked as an accountant at a Florida traveling agency, a calculated maneuver to get her discounted flights when traveling for races.

January 29th, 1956, was a notable one for Isabelle. She placed seventh at the 12-hour race in Buenos Aires and met her future husband, Alessandro De Tomaso while buying parts at a Maserati factory. Their mutual fondness for race car driving automatically drew them to each other.

"I think it was a relationship that was built on her number one love at the time, which was going fast,” her niece explained.

Later that spring, Isabelle revisited the Sebring track with Alessandro as her partner. Although they didn't finish because of a faulty gearshift linkage, this marked the beginning of the two frequently racing as teammates.

Not completely satisfied with participating in primarily female races, Isabelle departed for Europe in the spring of 1956. Here, she obtained a professional license through the Royal Automobile Club and regularly raced against male drivers. "I took off for Europe because I could race in all of the races that actually meant anything," Isabelle once told her nephew, William.

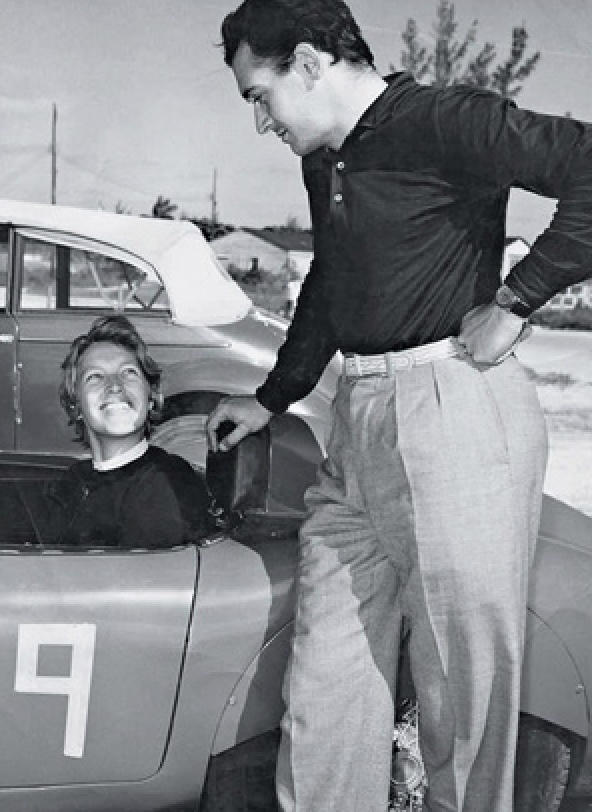

Isabelle and Alessandro

Isabelle was often only one of two female drivers competing in European races, but this never discouraged her; in fact, it may have fueled her motivation even more. "She loved being competitive, and she loved racing against men," Isobel explained. While relatively simple, these two assertions were significant leading forces in Isabelle's racing career.

Isabelle's time in Europe was characterized by many new people, places, and experiences. She led a life that most people can only dream of, traveling around European countries, winning races, and being celebrated at dinners by those who admired her.

"It couldn't have been more intoxicating," explains her niece.

It wasn't always luxurious, though. Lengthy trips from country to country were directly followed by long races, where Isabelle would use whatever remaining energy she had to compete against some of the world's most talented drivers.

"She tells stories about how sometimes they would be going from place to place and turn the motor off and push the cars so that they could save the gas for a certain period of time," recalls William.

In 1956 at the 12 Hours of Reims race in France, Isabelle's racing career was brought to a halt. Before the race, her partner Annie Bousquet had taken her Porsche 550 Spyder to be repaired at the factory, where it was finished at the last minute. After driving overnight to make it in time, she convinced Isabelle to let her drive the first leg, even though Bousquet hadn't slept the night before. On the 17th lap, her left front wheel left the track, and the car flipped over, causing Bousquet to lose her life.

Following the accident, a French motorsport authority called the Automobile Club de L'Ouest decided not to allow women to participate in its races—a ban that would last until 1971. Not only had Isabelle lost her friend, but she had now lost her right to race.

Isabelle and Alessandro's Wedding

One of the races the Automobile Club de L'Ouest oversaw was the prominent 24 Hours of Le Mans race in France. Isabelle applied to participate three years after the incident, but the French authorities were still afraid of receiving bad publicity. Alessandro, however, was able to participate.

"They said to me, 'If something happens, it's the end. Just think of the news.' They wouldn't let me race," Isabelle explains.

In 1957, Isabelle and Alessandro traveled to the United States to marry in Palm Beach. While the opportunities were even more limited for Isabelle now, they continued to race in Europe, South America, and the United States under different authorities throughout the late 1950s.

Driving together in 1958 at the Index of Performance in Sebring, FL, the newlyweds finished the 12-hour race eighth overall and first in their class, one of the most significant accomplishments of Isabelle's career.

Isabelle and Alessandro Win at Sebring

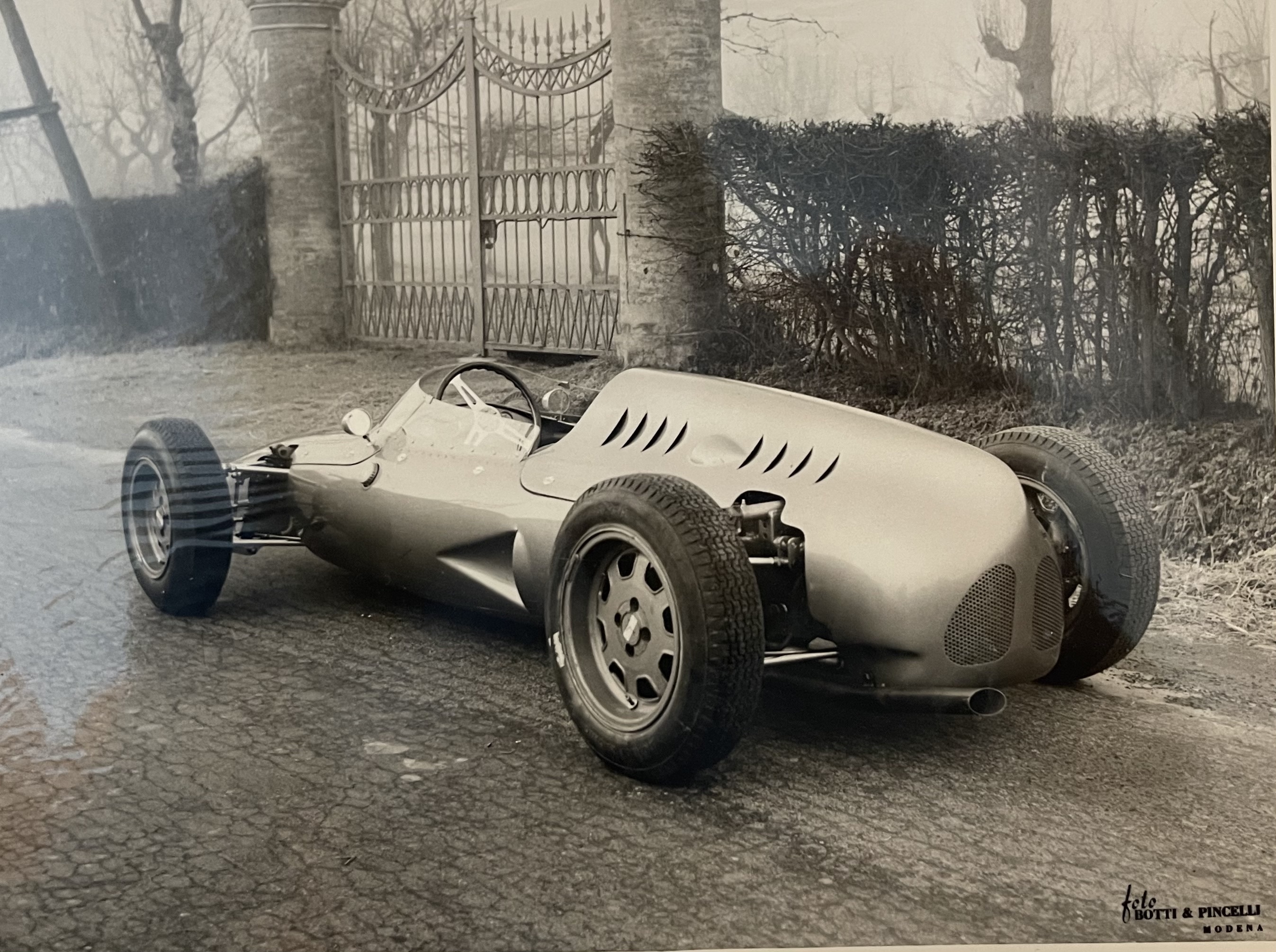

Two years later, Isabelle and Alessandro took their shared passion for racing and put it into developing their own company, De Tomaso Automobili. Founded in Modena, Italy, the company produced high-performance, hand-made, single-seater race cars. Although their priorities began to shift after its introduction, their love for competition remained strong.

This claim proved to be true in the mid-1970s when my dad, Mac Haskell, and his brother, Amory Haskell, visited their aunt and uncle in Italy. Upon their arrival in Rome, a drive home from the airport quickly escalated into a competitive race to Modena, my dad with Isabelle and Amory with Alessandro, each riding in their De Tomaso-designed cars.

"I just remember how incredibly exhilarating the whole experience was and how gifted my aunt was at the wheel of that beautiful car," he recalls. Evidently, Isabelle and Alessandro's retirement from racing on the track did not preclude them from continuing their passion elsewhere.

Ralph Nuanez, an avid car collector of 30 years who has specialized in sports cars from 1965 to the present, has admired the De Tomaso brand for many years. During Isabelle's racing era, "It was all about who can make the fastest cars and which cars handled the best," Nuanez explains.

Using Isabelle and Alessandro's extensive knowledge of sports cars, they created three models of the De Tomaso race car: the Pantera, the Deauville, and the Longchamp, the Pantera being the most popular.

"They took the Pantera and used an Italian body, but they put an American Ford engine in it to make it more reliable," describes Nuanez. The combination of the two elements attracted buyers all over the world.

Following Alessandro's death in 2003, De Tomaso stopped producing cars. The company went dormant until 2014 when Ideal Team Ventures investment manager Ryan Berris discreetly acquired the company at an auction. After many years of working behind closed doors, Berris unveiled the latest De Tomaso model, the P72. They began production in December of 2022, and the starting price is around $1.25 million.

Although the new model bears little resemblance to its predecessors, it ensures the brand will endure for many years. And most importantly, so will the De Tomaso legacy.

As our conversation settles, I retrieve some photo albums from the old wooden shelf and sit beside Isabelle, using her stories to guide me through each photograph. Wedged between the pages is the occasional newspaper, each yellowed with age and delicate to the touch. The formal language, conservative clothing, and snappy headlines are a window into another era, a time when the world was different, and we would read the news in a physical form.

While I carefully sift through each photograph and article, I can't help but utter, "Look, that's you!" whenever I come across an image or mention of Isabelle. Each time I do, though, her smile reaches cheek to cheek in contentment, and I can't help but mirror that same emotion.

Our evening extends into dinner at Swifty's with her sister, Hope Haskell Jones. When my dad arrives to drive us there, each attempt he makes to assist Isabelle's maneuver to the car is promptly followed with a firm "I've got it." Despite being 93 years old, her independent spirit has never faltered.

As we dine outside the busy restaurant, I listen as the three of them reminisce on memories from their hometown in New Jersey, occasionally trying to envision myself there with them. Despite the differences in our individual life paths, I find comfort in knowing that we all share a deep and meaningful history.

Halfway through the meal, my dad's cousin and his wife stop by our table for a quick hello. While everyone catches up, I remember my dad telling me that this project has done a great deal in "bringing the family together." He was right; I hadn't seen some of them in years, and it wasn't until we sat down at this dinner that I truly grasped the weight of his statement.

Isabelle (left) and Hopie (right)

I observe the sisters sharing their main course, taking turns savoring the paté Hopie raved about when we first browsed the menu. Watching them interact feels like a glimpse into my sister and I's future, and it instantly fills me with an immense appreciation for our relationship.

Our night ends as we say our goodbyes in front of the restaurant. I thank Isabelle for allowing me into her life and express my admiration for her one more time. The next day, my dad and I depart for our drive back, making a few pit stops at his childhood home, neighborhood church, and places where he once made his most cherished memories. In these moments, I recognize that my gratitude extends much further than just a thank you to Isabelle, and I look to my dad in heartfelt appreciation for him, our family, and the privilege I have to be a part of something so special.

"It's quite a family history you were born into. Good and bad, happy and sad. But, most certainly not boring," my dad says as we head home.