It’s a warm day on Easter at Torrey Hills Park in San Diego as Erick Gomez-Villeda sets up cones, goals and soccer balls for another training session. He’s got agility and shooting training lined up, as well as a scrimmage game for the day. However, Gomez-Villeda has to be on his toes as he may have to adapt to whatever circumstances arise. And adapt he does.

Expecting a group of six, he realizes that it’s Easter and recognizes that he may have fewer players to train today. His assistants — or buddies, as they’re called — arrive first, getting ready to help out with whatever needs to be done. They’re high school kids volunteering for TOPSoccer to help kids with disabilities play soccer and have fun. The turnout for the day is two. Gomez-Villeda makes it work and focuses on Ayan and Jules’ shooting.

He does his best to keep the boys moving, with Ayan getting a break to go on the slides at the playground after 20 minutes of soccer. At some point, Ayan leaves for the day, leaving Jules with coach Erick and the buddies. He gets Jules to run across the small pitch he’s set up with the goals, having Jules dribble and shoot for 20 minutes. Gomez-Villeda says it’s the most he’s ever seen Jules run — and he just recently broke his toe.

Soon, the hour-and-30-minute training session is over and the preparation for next week’s session begins. It’s just another practice in the TOPSoccer program that’s designed to keep people with intellectual, physical, or emotional disabilities active and moving around in a safe environment.

“There’s nothing special about them. These are kids that just want to come out and play.” said Gomez-Villeda, a TOPSoccer coaching instructor and coach of the Del Mar Carmel Valley Sharks.

It’s been over 30 years since the program has been in existence, but TOPSoccer is one of those programs that provide an affordable environment for those with disabilities to participate in recreational soccer. It started with an idea from two college students, Tommie Smith and Annette Schroeder, who volunteered at the special olympics and suggested to the special olympics committee that soccer should be available year round rather than only hosting an event for the disabled once a month.

In the program’s infancy, it started off with eight kids. Half were diagnosed with down syndrome, two with autism, one with cerebral palsy and one undiagnosed according to Sandy Castillo, director of the Cal South district for TOPSoccer. Fast forward to the current day, a majority of the players in the program are somewhere on the spectrum.

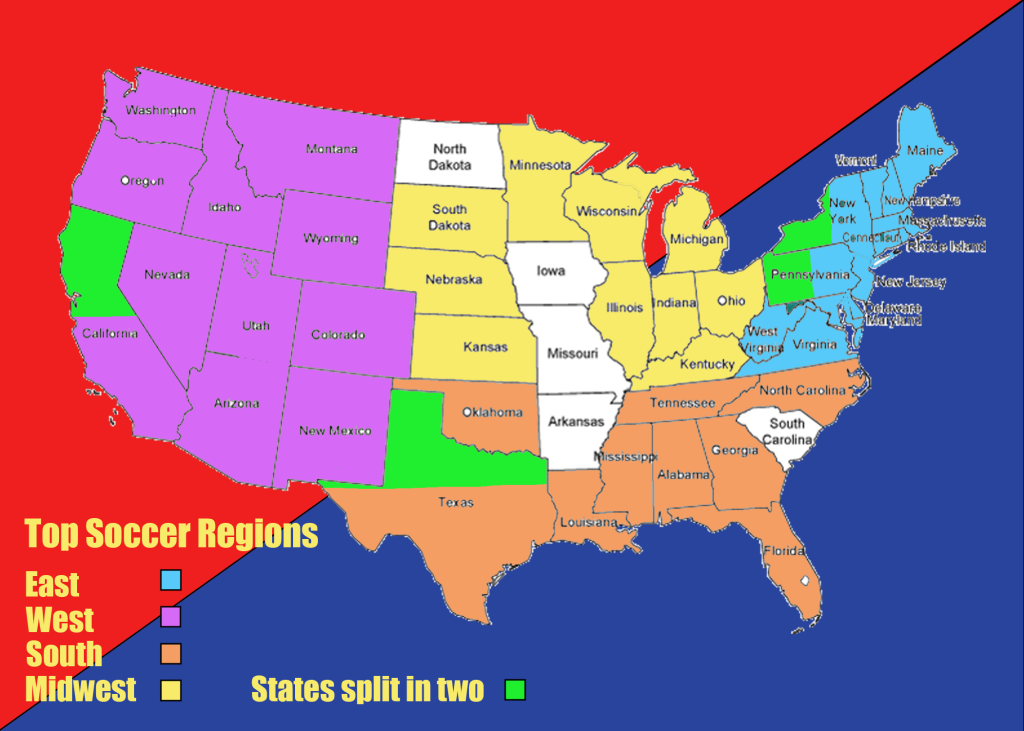

Over time, the program received funding from US Youth Soccer and Adidas to keep it running, and more companies would sponsor it later on. The program has provided accessibility for those interested in playing soccer to find a community that wants to help them grow and develop their playing abilities as well as find a space to connect. As the program continues to grow, it branches out to more and more states, becoming nearly nationwide with its operation.

“What we try to do through our program is to create an environment in which all children, young adults [and] people are able to experience the game of soccer,” said Jim Watson, the coordinator of the TOPSoccer program at Orange Junior Soccer Club. “It really is trying to share the beautiful game with all people and certainly not having any types of disabilities or other challenges prevent somebody from experiencing soccer … we are trying to create a very inclusive and safe, nurturing environment for these children and young adults; in some programs, there are older adults that also participate.”

Adapting to the changes in acceptable language over 30 years has been one of the challenges that the coaches have faced. With help from local special education teachers, they’re able to keep current with language that is deemed admissible when referring to the kids. However, all the coaches agree that the best way to talk about them is just to say their name, and not treat them as different from everyone else.

With 5.4% of people aged 5-17 having a disability according to the ADA, it’s important that there are options for disabled youth to remain active, all while making sure that costs don’t deter families from putting their kids in a safe and competitive setting.

It’s proven to be an experience that’s tightly connected those involved. Participants share experiences that demonstrate TOPSoccer is the right space for those trying to make an impact in their community.

“We pay a fee to Cal South for our insurance to make sure that all our kids are covered by the insurance. Cal South allows our players to play at a reduced fee instead of paying like 12, $15 we pay $7.50 a player,” Castillo said. “Cal South also provides startup equipment, field equipment, goals, pennies for any of the programs that are under Cal South.”

The fee to join a TOPSoccer program varies from area to area, with some being free to others charging a low fee of around $25-30. While some programs are funded by their club’s other operations to cover costs, others need those extra funds or view the charge as an incentive for the parents to continue to bring their children to practice as they’re invested into the program.

“We charge a fee, but it’s a low fee … I call it a buy-in, because a lot of times they’ll say it’s free, just show up, and maybe they’ll show up once, maybe they’ll show up twice. But now if they have something invested into it, it makes them show up almost all the time,” Gomez-Villeda said. “And a lot of times the first or second time after that, if they show up, they want to keep coming back. Some of these kids, you can get them off the field.”

For Kindra Gilbert, a TOPSoccer player at JUSA, she enjoys being around to help others on her team play soccer. It’s also a place where she can hang out with some of her friends and just get better at playing.

“Sometimes other people on my team don’t know what to do, so I just help em out. So I just do defense and then we switch it up sometimes. So I play forward also,” Gilbert said. “For me, I guess probably doing soccer with my friends and learning to get better on your sport and stuff [is why I play].”

Gilbert’s been with the program for nearly 5 years. Having a space where she can just have fun, help the other kids, and be with her friends, Ashley and Mikayla — the group with whom she’s dubbed the “Three Amigos” on the pitch — is what TOPSoccer is about. Whether Gilbert is playing around with her friends or cheering on the other players in her team, it’s an embodiment of the type of program TOPSoccer wants to be and is.

TOPSoccer aims to provide a balanced level for players when competing against each other in terms of skill level to keep it fair. For Cynthia Gilbert, Kendra’s mother and coach at JUSA, they set up their players into groups for their practice sessions.

“We have grown up adults into their forties and then we have kids all the way down to like four or five. So we’ll usually divide them up into three different areas. We have the little middles and then the uppers.” said Cynthia Gilbert.

It’s the best way to make sure that everyone is placed fairly to provide a level playing field for all kids and adults. Cynthia Gilbert describes the littles as beginners and young children, middles being for intermediates, and the uppers being for the more advanced. There is no set evaluation for the players that locks them into these groups, allowing them to move up and to down to adhere to their skill level.

Many of the coaches had to go through hurdles initially in order to understand the style in which they have to guide the kids into playing soccer and having fun. Another teaching moment was realizing that the athletes are also just kids at the end of the day, and just want to have fun like everyone else.

“Their diagnosis does not define who they are, it’s just a part of them,” Castillo said.