Marie was 19 years old when she got married. And she was 20 when she tried getting a divorce.

But it wasn’t so easy.

At the time, Marie — who asked to be given a pseudonym due to the sensitive nature of her story — was a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. She grew up predominantly in Mesa, Arizona in what she calls a “bubble” due to its heavy population of Latter-day Saints. Both her parents were, and still are, members of the church. Her dad’s ancestors were pioneers — part of the mid-19th century movement led by Brigham Young to find a place for the LDS people to settle.

Marie wasn’t just a Christmas-and-Easter church-goer; she was devout, committed and involved. Church every Sunday, Mutual every Wednesday and articles of faith classes in between. All of her friends were LDS — and that was intentional.

So, it was only logical that when a man entered Marie’s life, she would look to get married in the LDS Temple.

Here’s how the official church website describes marriage in the temple: “Temple marriage is aptly referred to as sealing because it seals a couple and family together forever.”

Divorce, in other words, is frowned upon: “If, instead of resorting to divorce, each individual will seek the comfort and well-being of his or her spouse, couples will grow in love and unity,” according to the church.

Even when, as was the case with Marie’s husband, the spouse is abusive.

“I was told to stay married to a guy who was physically abusing me because that’s better than divorce,” Marie recalled.

Marie explained that even after she legally divorced her ex-husband, she was still married to him within the church due to the binding nature of temple marriages. She had to write to the First Presidency — the president of the church and his two apostles — to get her sealing canceled and could only do so with the permission of her ex. Marie found the whole process “very outdated,” “sexist and dehumanizing.”

While Marie was grateful to have the support of her family throughout the process, she was “very, very mistreated as a member” by the larger community.

“The Mormon men were so rude to me about it,” she said. “I was told I was damaged goods to my face.”

Marie left the church shortly after her divorce, about six years ago. While her experience was nothing short of traumatizing, she added the caveat that things seem to be getting better.

“My sister recently got divorced,” she said. “She’s still Mormon, but she had a bit better of an experience.” Marie chalked this up to the fact that her sister lives in Washington, D.C., not Utah as Marie was during her divorce.

Marie is currently studying marketing at the University of Utah and is a social worker at Primary Children’s Hospital. She hasn’t been religious for six years and plans to raise her children, if she has any, agnostic. She sometimes finds it hard living in Utah due to the religious dynamics. In fact, Marie said she even has difficulties being friends with Latter-day Saints, although she has respect for everyone: “It’s like we’re living in two worlds almost,” she said.

In addition to her messy divorce process, Marie cites her undergraduate studies in social work at Utah State University as another catalyst for her decision to leave the church. As she began to learn more about societal inequalities, she started questioning how the church might be perpetuating these dynamics.

“The policies on gay marriage and just the way that gay people were treated in general by members are what first opened my eyes to all of it,” she said.

“We believe marriage is between a man and a woman, okay? And we don’t believe in people moving in together that aren’t married.“

— Scott Tanner, official church spokesperson

Marie is referring to the church’s belief, which comes from its scriptures, that marriage should be between a husband and a wife.

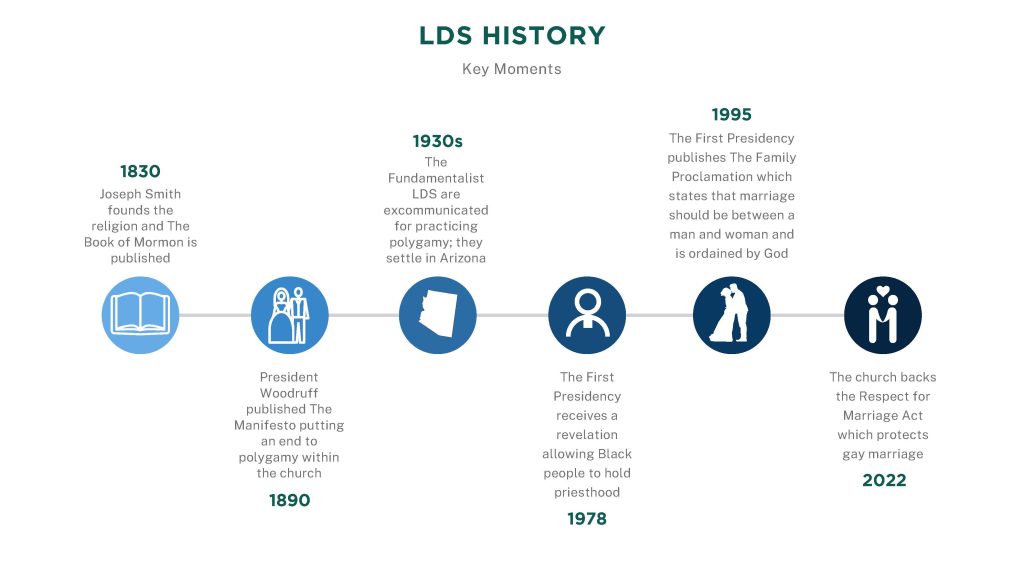

It’s worth noting, however, that the LDS church recently backed the Respect for Marriage Act — federal legislation that safeguards same-sex marriage as long as it doesn’t infringe on religious freedom.

For Marie, the church’s stance on gay marriage was the first domino — women holding priesthood, which is forbidden by the church, and sexism throughout the organization were next.

Marie’s departure from her faith — which was at one point so deeply intertwined with her life — is particularly dramatic. And it’s only one example in a pattern of young people — millennials and Gen Z — leaving the church.

Gabi, who preferred to leave out her last name due to privacy concerns, graduated from Brigham Young University Idaho in 2021. She grew up in what she called an “extremely devout” family but started having feelings about wanting to leave the church after graduating from high school. Going to a university sponsored by the church while having religious doubts made college life difficult for Gabi: “It made me feel like I had to pretend to be someone who I wasn’t for three years.”

While she admitted she still has a lot of respect for the church and for religion in general, aspects of the culture didn’t sit right with her — like not wearing certain types of clothes and refraining from sex before marriage.

“I mean, that’s not necessarily what the church teaches, but that’s kind of what the culture has evolved to be. So it’s less doctrine-based and a lot more culture-based for me,” Gabi said.

A 22-year-old Utah native and University of Utah alumna whose family history goes back to the beginnings of the church left when she was 17. She asked to remain anonymous due to her family’s involvement in the church; some of her extended family members, from whom she has distanced herself over the years, continue to try to convince her to come back.

“I honestly spent a lot of time in therapy getting over all the ideas that they put in my head. I think it really messed up the way that I think about my values and the way that I feel guilt towards things.”

— University of Utah alumna

The biggest thing that led her to distance herself from the church, she said, was misogyny within it, including the church’s policy on divorce.

“They teach women to be very obedient and subservient in that way. They don’t really want women having a voice,” she said.

She views the church as being based in fear: “One of the big parts that made it so hard to leave is because they raise you in it thinking that any other ideas are like from Satan.” She shared that she’s spent a significant amount of time in therapy trying to unlearn the ideas that were instilled in her from church.

The effort she has put in to get to the point where she is today — somewhere between agnostic and spiritual — has been worth it. The Utah alumna said she has felt more happiness during her time away from the church than she ever did in it.

Of course, these are just three individuals’ stories with the LDS church — and there are over 16 million members worldwide, according to 2020 church data. But, these stories are, in fact, telling of a larger trend of secularization of the younger generation in the U.S.

In 2020, church membership across all religions in the U.S. dipped below 50% for the first time in at least 80 years, according to a decades-long Gallup survey. Membership is now down by over 20% since 1999, and youth are driving the numbers.

Rev. Brandon Harris is the associate dean of religious life at USC. He is well aware of what he calls “the secularization of American society.”

“Religious institutions are no longer viewed as the center of people’s lives,” Harris said. “People have other ways of finding meaning or community and belonging.”

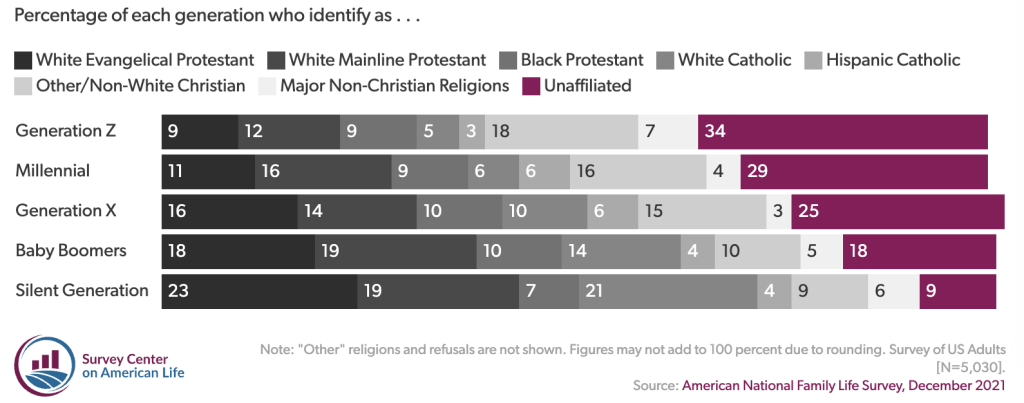

Gen Z in particular is the least religious generation yet — more than a third of Gen Z in the U.S. identifies as “religiously unaffiliated,” according to a study from the American Survey Center. Millennials are only slightly more affiliated. Baby boomers and the silent generation have the highest percentage of religious members.

“Millennials and Gen Z tend to be skeptical of over-politicization of religion from either side,” Harris added.

While membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints continues to grow in some areas of the world such as South America, the church has been reporting significantly lower rates of growth in the U.S. compared to its heyday in the ‘70s and ‘80s. In 2017, growth rates in the church declined to their lowest levels since 1937, and convert baptisms fell to a 30-year low, according to an article from the Journal of Mormon Social Sciences Association by David G. Stewart, Jr.

Again, it appears the trend in the LDS church is also generationally aligned. In 2014, 22% of Mormons were between the ages of 18 and 29 years old, down 2% since 2007, according to Pew Research. On the other hand, the percentage of members aged 50-64 increased by 3% over the same period.

The LDS church is particularly vulnerable to a trend of secularization for a couple reasons. Firstly, it’s a relatively young religion meaning it’s still in a growth phase. Unlike Catholicism, for example, the LDS religion was founded less than 200 years ago. Thus, to withstand the test of time, it can’t afford stagnant membership.

Secondly, one of the most defining features of the church is its missionary program. Missionaries are young adults under the age of 25 who are assigned a location in which they spend a year and a half (for women) or two years (for men) spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ. Although serving a mission is not required, it is highly encouraged for those who are eligible. If young people continue to opt for a secular life, the strength of the missionary program dwindles.

With these unique factors in mind, there is reason for the church to be worried.

“There is a lot of concern about disaffiliation of young people in North America,” said Paul Edwards, the executive director of BYU’s Wheatley Institution. The Wheatley Institution’s mission is to engage “students, scholars, thought leaders and the public in research-supported work that fortifies the core institutions of the family, religion and constitutional government,” according to its website.

Young ex-LDS members, like Marie and Gabi, named many reasons for leaving the church: misogyny, inequalities within the church, its policies on gay marriage and divorce and other social justice concerns.

But when current members of the church were asked to ponder why the church is seeing decreased interest from the younger generation, they came up with different theories.

Paje Rasmussen is a 21-year-old Utahn currently serving a mission in the Los Angeles area. When asked to reflect on why she thinks people leave the church, she said this: “It’s all about them. They are God. If it doesn’t fit in their schedule, if it doesn’t fit their way of life, if it doesn’t please them, they don’t want to do it.”

Rasmussen recognizes that religion “invites us to do things that are difficult.” It can be inflexible and inconvenient, and the younger generation isn’t always willing to put up with those inconveniences.

Ku’ulei Annandale, Rasmussen’s missionary companion, echoed a similar sentiment. “I feel like it’s really popular to have this mindset of I’m free to do whatever I want,” Annandale said. “I think there’s very much a mindset of instant gratification and wanting that information or that answer now,” she added.

The two young missionaries recognize that their faith is demanding. But for them, it’s worth it. In their minds, stepping away from religion is almost like choosing the easy way out — the route that’s more flexible and doesn’t ask you to change, or rethink, your nature.

When asked why he thinks the membership in organized religion in the U.S. is stagnating, Scott Tanner, an official spokesperson for the L.A. region of the church, said, “Well, I guess the first word that pops into my head is the brainwashing.”

He gave this example: when you turn on the TV to any major network and watch the commercials, you’re inundated with messages that “happiness is a new car” or a “really good lawn mower.”

“Gen Z, they don’t know,” Tanner said. “They don’t know where to find lasting happiness.”

Tanner explained a similar concept that the two missionaries alluded to: Gen Z knows only happiness as it relates to materialism — short-term happiness, that is. Religion, and in this case the LDS church, is the path to long-term happiness.

Edwards, the executive director of BYU’s Wheatley Institution, had a different theory on the secularization trend, particularly as it pertains to the LDS faith.

“I think that with institutionalized religion, I think generationally people are kind of asking themselves, do I have to buy the whole thing?” he said.

Edwards gave a few examples of how this notion of picking and choosing what works best for you has increased over time. Back in the day, he explained, if you wanted to listen to one song from a particular artist, you’d have to buy the whole record. Now, you simply download the song you like on Spotify. Another example: season ticket sales for something like the symphony orchestra are declining. Instead, people pick and choose which shows to go to based on their interests and availability.

The point is, as Edwards believes, religion doesn’t work the same way. You can’t buy into the LDS’ belief in priesthood but not into the belief that sex should wait until after marriage. You can’t come to church every Sunday but still drink alcohol and coffee, both of which are generally prohibited in the LDS faith. Picking and choosing isn’t an option.

Dr. Michael Stanley, the director of the L.A. Institute for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, harped on a similar idea in this hypothetical: “If I’m comfortable doing what I’m doing, why should I avail myself to an organized religion and have other people telling me what I can and can’t do?” he said.

From those responses, it’s clear there’s a disconnect between why ex-LDS have left the church and why current LDS think people are leaving the church.

Harris, the associate dean of religious and spiritual life at USC and an outsider to the LDS church, added another factor to the equation: a rise in general skepticism of institutional authority — we see this skepticism aimed towards political figures, powerful business people and, of course, religion.

When listening to the departure tales of Marie, Gabi and the University of Utah alumna, it’s easy to view the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as a soon-to-be thing of the past.

In his recent article entitled “The End of Growth? Fading Prospects for Latter-day Saint Expansion,” Stewart put it bluntly: “The vision of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints becoming a major world faith has become increasingly implausible.”

But the reality is, on the other end of the spectrum, you have devout missionaries like Annandale and Rasmussen, who, at the age of 21, have been devoting every day of their life for a year and a half to spreading the word of the gospel.

And it’s easy to hear the passion in the way they speak about their faith: “There are worldly things and there are spiritual things. There are eternal things. We will only take one of those with us when we die,” said Rasmussen. If we want to find joy, she continued, “our generation will have to learn to find and prioritize the spiritual things, the eternal things.”

Of course, the “eternal things” she’s referring to stem from a belief in God.

Based on the disconnect in the understanding of members’ reasons for leaving between current members and ex-members themselves, there seems to be a widening gulf between LDS members and their nonreligious counterparts.

Marie sees this everyday living in Utah — the state with the most LDS members in the country. And to her, it’s reflective of the broader relationship between current and ex-members.

“You either have ex-Mormons, or anti-Mormons, and then you have Mormons, and there’s no in between,” Marie said. “It’s two different realities.”