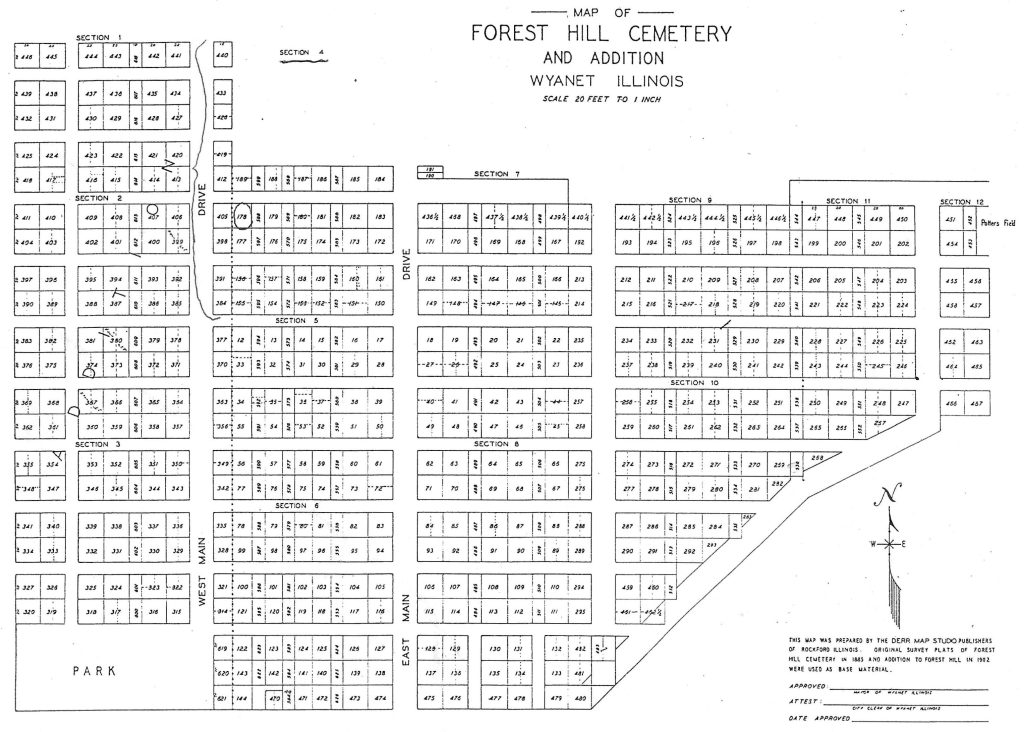

On a frigid February morning, 77-year-old Barbara Martin trudged through a small town cemetery called Forest Hill. As she marched through the rows of headstones, she mumbled to herself while scanning the cemetery map in her hands, searching for a specific gravesite. She held up the map, “Do you see those hills between rows of headstones? Those are what separate the sections,” Martin said.

She was looking for section four, plot 178, the final resting place of the McFarland family. A distant relative of this family reached out to Martin on the website Find A Grave and asked her if she would come down to the cemetery to see if there were headstones for the buried couple’s children at the plot.

As an amateur genealogist of almost 20 years, Martin is no stranger to Forest Hill Cemetery. Located in her hometown of Wyanet, IL, this cemetery has been a focal point for her personal family history research. Now, with little of her own family tree left to document, Martin helps others she connects with on Find A Grave and Ancestry to find information on their loved ones. Of the 3,100 graves in Forest Hill, Martin has documented 2,500 of them on Find A Grave.

Despite leaving this community in 1968 for college and a career, Martin still returns to the site several times a month to help strangers learn more about where their ancestors come from, including the McFarlands.

Martin discovered the McFarland Plot at the edge of the cemetery, where some of the oldest graves are located. A large granite monument emblazoned “MCFARLAND” loomed over three much smaller eroded headstones.

Martin knelt and started scraping away the algae from one of the tiny stones with a window squeegee. Then, she sprayed shaving cream over the front of the stone and rubbed it into the grooves of the inscriptions. She retook the window squeegee and scraped off the excess shaving cream.

“Ah, there. See that there? You can see the name now,” Martin said. Satisfied with her discovery, Martin photographed the stone, washed the shaving cream off the grave marker with a jug of water and repeated her process with the other two small headstones at the plot.

Her Mother's Legacy

After teaching math to high school students in the Chicago suburbs for 33 years, Martin retired in 2001, but she wasn’t ready for a leisurely retirement just yet.

“I was only 54 when I retired,” Martin said. “I need something to do. If I didn’t, I would have gone crazy sitting in my house.”

Martin taught community college classes, took computer classes at her local library and helped watch her sister’s young children. But when Martin’s elderly mother lost her fight to breast cancer in 2004, an interest in her family history was sparked in Martin, according to her sister, Lori Richmond.

“Mom was always interested in learning more about her ancestry, given that her mother came off the orphan train,” Richmond said. “So, when we were told that our mother’s cancer was in its final stages, we thought we had time to ask all those historical questions that you never take the time to ask. Why was her mother put on the orphan train? Where did they come from? Who were their parents, and where did they come from? Unfortunately, within a day, the cancer affected her mind, and we were left without answers.”

Following her mother’s passing, Martin was cleaning out her childhood home and stumbled upon a newspaper article about the New York orphan trains and two incomplete family data sheets with names she didn’t recognize. “I was sitting in a storage closet when I found them and just wondered why my mother had kept them,” Martin said. “I started toying with the idea of finishing the research my mother had started.”

The curiosity stuck with Martin until November 2007, when her local library offered an informational workshop on Ancestry.

“I attended this meeting and walked away thinking I could access all my family records by not going to court houses, cemeteries, genealogy societies, etc,” Martin said as she laughed at herself. “Boy, was I wrong?”

Ever since that workshop, Martin has been an Ancestry member, marking the beginning of her so-called “genealogy addiction.”

“My mother was the youngest of 13 children, and my father was the oldest of four children. Only my father’s brother lived in our town, and the rest of my relatives were out of state,” Martin said. “The more I learned from my research about where my parents came from and where my relatives lived, the more I wanted to know.”

Martin is a certified junkie when it comes to family history. In addition to Ancestry, she spends over $500 a year on genealogy resource subscriptions plus extra fees for paywalled records not included in her main supply of subscriptions. However, Martin’s most difficult successful discoveries have been due to her collaboration with fellow amateur genealogists.

A Distant Cousin

Only a year into her new hobby, Martin was contacted by a fellow Ancestry user named Nancy Cluff-Siders for help. Cluff-Siders had been doing her own genealogy research for 30 years the “old fashioned way by going to courthouses, cemeteries, the whole nine yards,” according to Martin. The woman reached out to Martin because part of Martin’s family tree matched her own.

At this point, Martin had traced her mother’s side of the family back to her great-great-grandfather, Pernell Cluff, in Pike County, Ohio. Cluff-Siders, who lived in Pike County, had information on a Rueben Cluff and a Catherine Ann Hinton-Cluff, who she believed to be the parents of her own great-great-grandfather, Charles, and possibly Martin’s Pernell. However, Cluff-Siders had no documentation to prove this theory and hoped Martin would join her to hunt down the information.

The pair decided to have two of their male Cluff relatives do a DNA test to see the outcome and do their respective sleuthing while they waited for the results. Cluff-Siders went to Pike County genealogical societies, courthouses, cemeteries and other local resources to find more information on Rueben. Martin wrote letters to men in Columbus, Cincinnati, Hillsboro and everywhere else in Ohio she could find men with the last name Cluff to see if they were part of the family tree and had any information.

The duo struck gold when the DNA results came back, showing that the pair were indeed related. However, these results were just another clue because they alone didn’t prove that Reuben and Mary Ann were the parents of each woman’s great-great-grandfather.

So, Martin turned to the Church of Latter-day Saints, which keeps millions of microfilm records to support genealogy research. Martin found a microfilm listing the inheritance of Reuben Cluff’s land to all his sons, including Charles and Pernell. This document proved that the pair’s great-great-grandfathers were indeed brothers, making them distant cousins.

“We were two giddy girls who had made a profound revelation,” Martin said.

From hundreds of miles away, Martin and Cluff-Siders celebrated their discovery and decided to stay in contact.

“Nancy became my mentor in a way,” Martin said. “She was a bit older than me and had been researching much longer than I had. She always offered advice when I was stuck in a rut in my research. It was a great partnership.”

Cluff-Siders’ mentorship proved especially helpful in 2010 when Martin found herself at her biggest roadblock yet.

The Man in Montana

In 2010, Martin’s research led her to distant relatives in Montana, but one of the men’s paper trails she was researching had dried up. At Cluff-Siders’s suggestion, Martin decided to check Find A Grave.

“I couldn’t find anything about this young male after a certain age,” Martin said. “And I couldn’t find it on Ancestry, I couldn’t find it on FamilySearch, so I thought, well heck, let me try Find A Grave. And lo and behold, there was a memorial to him with his birth date and his death date, and he died at the age of 18, and that’s why I couldn’t find him.”

A stranger had uploaded a photo of Martin’s relative to the website, and that was how she found the information she needed to continue her research.

“I was so thankful to have found him that I saw that as my calling for Forest Hill because I grew up in this town, and I thought that could be my legacy to others who are searching for long-lost relatives,” Martin said.

Martin began documenting graves at Forest Hill soon after her Montana discovery so that others could find their loved ones’ memorials even from states away as she had. She would go through the older cemetery sections, photograph the headstones and upload the information listed on the stone to Find A Grave.

However, some of the stones were so eroded and unkept that they were unreadable. Determined to document as many graves as possible, Martin searched for a way to make them readable again and discovered the critical tool was shaving cream.

“We’re talking stones being there from the 1850s on, and there’s a lot of stones in there that are worn away,” Martin said. “So now when I go to a stone that I can’t read, I get out my shaving cream, I lather it up, and then I take a window squeegee and squeegee off the excess, and lo and behold comes to life all the information you care to read. After I take a picture of it and transcribe it, I take water and rinse off the shaving cream, and we’re good to go.”

Click to interact with Martin’s cleaning kit. Kit contains shaving cream, gallon of water, window squeegee and bath towel.

For each of the 2,500 grave listings Martin has made on Find A Grave, she continues to manage and update with information people request. Though she doesn’t go out and randomly photograph headstones anymore, Martin will go and search for headstones at Forest Hill at the requests of strangers who reach out to her on Ancestry and Find A Grave.

She will also visit the local genealogical society to search for information others request. Local resources, like societies, hold information that often can’t be found online, such as private funeral home records. So, for many, Martin is their only way of accessing these documents.

“Our cemetery records are our star source, and they are not on the internet,” Program Chairman of the Bureau County Genealogical Society, Elaine Newell, said. “These list people that are buried in the cemetery but may not have a tombstone, and so, that’s the only clue that people have that that person was actually here.”

“Anyone can go to cemeteries and record headstones and put it on Ancestry or Find A Grave, but Barb is helping people beyond that,” President of the Bureau County Genealogical Society, Carol McGee, said. “People would be missing a lot of documentation in their family research without her coming [to the society] for them.”

In addition to grave and documentation research, Martin has helped non-local individuals have headstones placed at their family members’ graves and veteran medallions added to headstones.

“Some of the best things I’ve discovered were with the help of other people interested in genealogy,” Martin said. “I hope that my work with Find A Grave has done that for someone else.”

Martin is on Find A Grave every week, checking her messages and assisting others who contact her.

“She started out researching our family, enjoyed the search, putting the puzzle pieces together,” Richmond said. “And in just talking about her hobby with friends, they have asked her to research their family trees. She enjoys this. There are costs associated with this, but she never charges people; this is her gift to them.”