Immediately after the event of a major earthquake, it is unlikely that many people will complain about a road or two being damaged, but as we begin to restore our communities, the damages made to our roadways will be noticeable and the effects widespread. The 1994 Northridge Earthquake caused extensive damage to the transportation network of the San Fernando Valley and several other areas. Caltrans reported the collapse of seven state highway bridges and 230 additional ones. While the damage to the bridges was more than expected, the 24 bridges that were previously retrofitted were able to withstand the strong shaking. Due to the extreme delays that bridge closures can have on traffic, Caltrans focused on retrofitting and repairing damaged bridges as a key factor in the opening of damaged roadway networks.

A felled structure that quickly became one of the most memorable examples of damage due to the 1994 Northridge Earthquake were the two bridges of the Santa Monica Freeway that collapsed on Fairfax Avenue. On any given day, an estimated amount of 341,000 cars crossed that section of the freeway. It is one of the most critical points of transportation for the area; at the time, the Los Angeles Times reported it was the world’s busiest thoroughfare. Not only did the city need to rebuild the collapsed bridge as a main connector, but also to expedite restoration processes throughout the Los Angeles area.

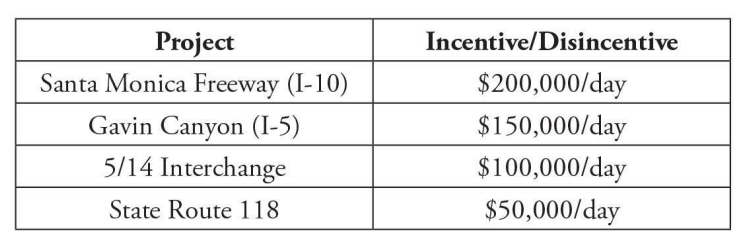

Due to the success of A+B contracting after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake in the Bay Area, the same type of procurement was used for the bridges of the Santa Monica Freeway. A+B bidding, also referred to as cost-plus-time bidding, is a method of determining the lowest responsible bidder for projects by requiring contractors to competitively bid the construction cost and the number of working days to complete all work. In other words, this model created an incredible monetary incentive for contractors to work quickly to make repairs, but also meant they would lose out on money for repairs that took too long.

The contractor that won the bid to rebuild the Santa Monica Freeway bridges was C.C. Myers, Inc., a contractor that was hired to do similar work under similar circumstances after the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Caltrans selected Myers to rebuild two damaged bridges on California 1 near Watsonville. It was the first time officials had used the incentive program, offering $30,000 for each day the company finished early. It was the first time using A+B contracting, so there was a far lower budget than the $200,000 they were offered in the Santa Monica rebuilding project. C.C. Myers, Inc. completed the Loma Prieta collapsed bridges 45 days ahead of schedule.

The use of the A+B contracting model after the Loma Prieta earthquake was experimental, which meant that the Northridge earthquake solidified the success of using this model for future incidents. In May of 1995, the Federal Highway Administration declared that A+B contracting is operational and no longer experimental, citing the Santa Monica Freeway repair as proof of its effectiveness.

A recent use of the contracting model is when the 10 Freeway in Downtown Los Angeles was damaged by a massive fire that began under the Alameda Street overpass in November 2023. Work on repairs began almost immediately after the fire was extinguished and, in collaboration with Caltrans, the contractor was able to finish the job in record time. The freeway was damaged on November 11; it was repaired and reopened in eight days.

Image courtesy of Google Earth.

In order to prevent further bridge collapses after the Loma Prieta earthquake, Caltrans established the Seismic Advisory Board, an independent body whose role is to advise Caltrans on seismic policy and best technical practices.

Over the past 30 years, Caltrans has invested over $100 million in seismic research that is used to update its seismic design and retrofit policies and standards. After the Northridge earthquake, Caltrans and local agencies undertook a Seismic Safety Retrofit Program that led to the retrofit of 4,931 bridges at a cost of nearly $14 billion. This investment resulted in improvements in seismic design practices and empowered engineers to design resilient new bridges and retrofit existing ones.

“What we learned from Northridge was making sure that, within a structure, that we have balance and stiffness. We needed more stiffness in our bridge designs, specifically pertaining to the columns that keep them up,” said Chris Taina, Caltrans Supervising Bridge Engineer.

After a large earthquake, new bridges are expected to perform well, but may be closed for a short time for inspection and to complete any minor repairs before being quickly returned to service. Bridges constructed or widened using post-1990 Seismic Design Criteria are expected to perform well with a minimal potential for collapse during a design-level earthquake. The performance of retrofitted bridges is expected to be significantly better than those that have not been retrofitted. That being said, it is important for the public to understand that it is impossible for every bridge (any structure, really) to be completely earthquake-proof.

“We do the best to make sure bridges aren’t gonna collapse, and that the roadways networks are gonna be usable, but, it’s not possible to make sure that you’re gonna be able to travel on every roadway, every public street. Mother Nature usually wins…Mother Nature is undefeated. So even though we design and have our best intentions to make sure that there’s minimal potential for collapse during a design-level earthquake, things can still happen. People need to take measures to ensure their personal preparedness,” said Taina.

Although the Seismic Safety Retrofit Program has been completed, approximately 620 additional bridges on the State Highway System have been identified as being vulnerable to seismic activity through recent seismic screenings. Many of these bridges may need retrofitting or replacement. Caltrans continues to fund the seismic retrofit of these bridges through the State Highway Operation and Protection Program (SHOPP), with the goal of reducing this number by 70 percent by 2028, but funding for retrofitting bridges is always a cause for concern for engineers.

“Taxpayers invest a lot of money in the transportation system through gas taxes and other revenue [Caltrans] receives, so its good for them to know what they can expect and that we’re being good stewards of the resources they’re providing us,” Taina said.

There is a fundamental rule in engineering, that a dollar spent, say for example on bridges…will buy you a lot more than the same dollar if you are retrofitting old bridges. That’s why retrofitting old bridges costs money. And there’s gonna be a balance on how much money you’re spending, and what kind of a performance you’re going to get out of it, because money is very limited.

Mark Mahan, Caltrans Professional Engineer