With no instruction manual for growing old, gay older adults have carved their own paths into new models of later life.

Meet the men of Maison d’Être, a household that defies tradition, embraces chosen family and serves as a microcosm of the unique challenges and joys of being a gay elder.

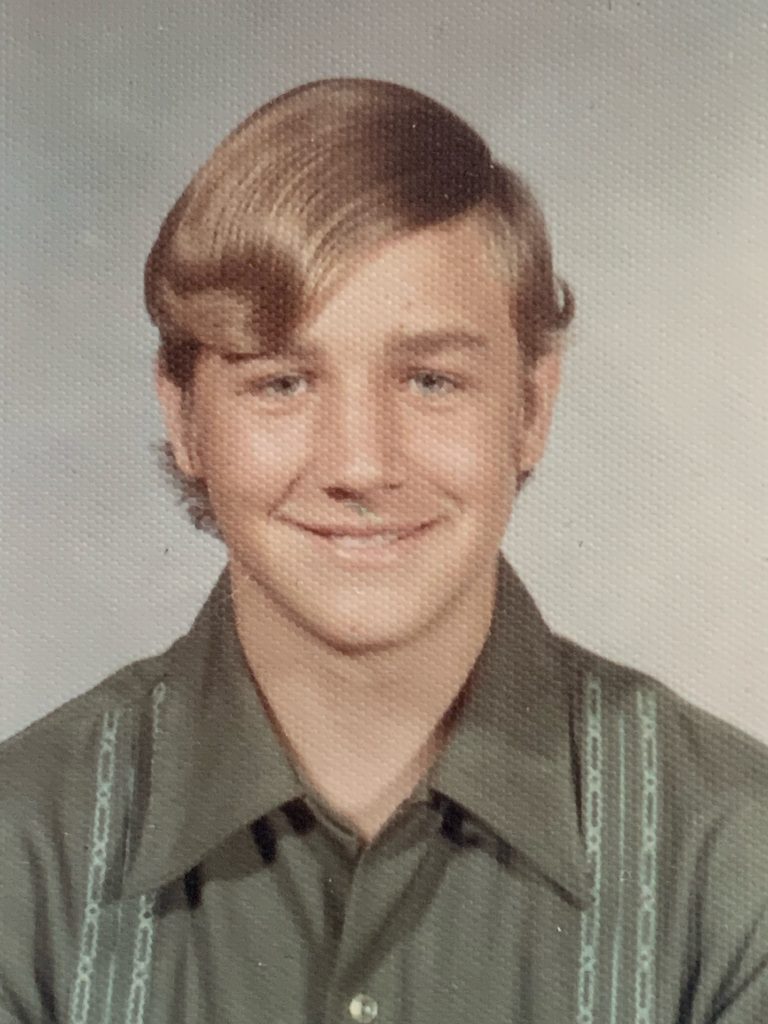

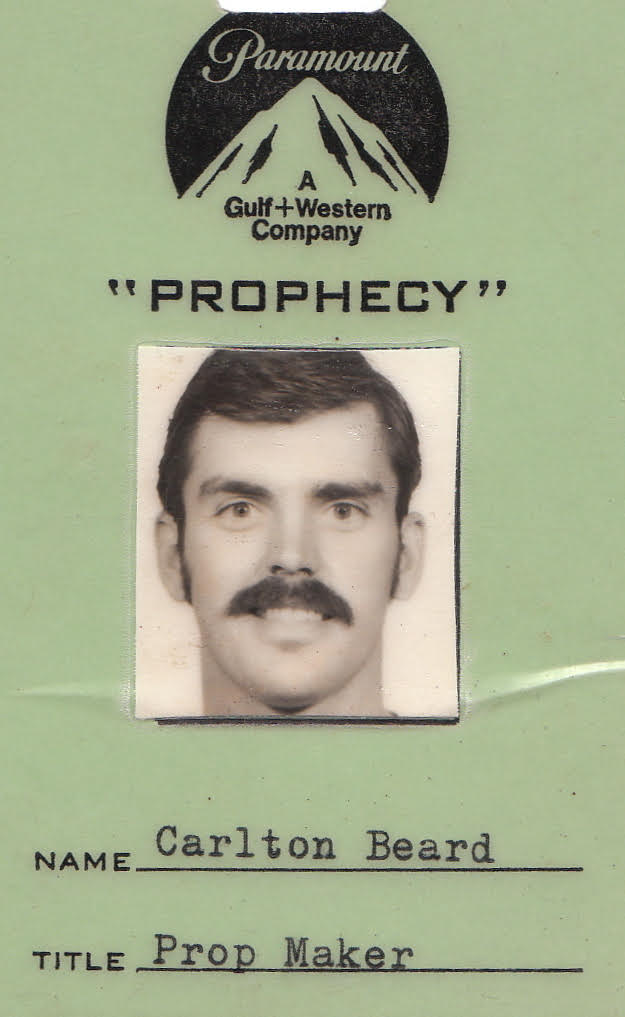

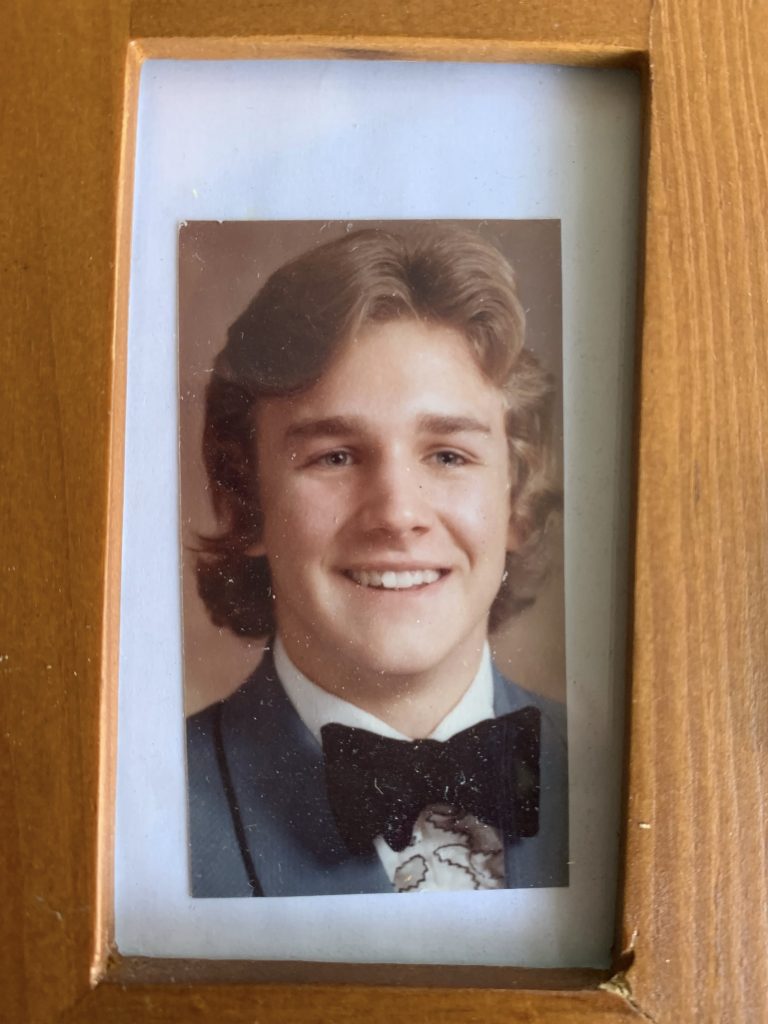

When Richard Beard was in his early 20s, he made a promise to himself that he swore to never break: to commit suicide at 30.

“I saw what older gays were treated like,” Beard said. “It was a dead end at 30. It was pathetic after 30. It was those creepy guys that I dodged. And so I never wanted to be those guys.”

Thankfully, Beard broke his promise.

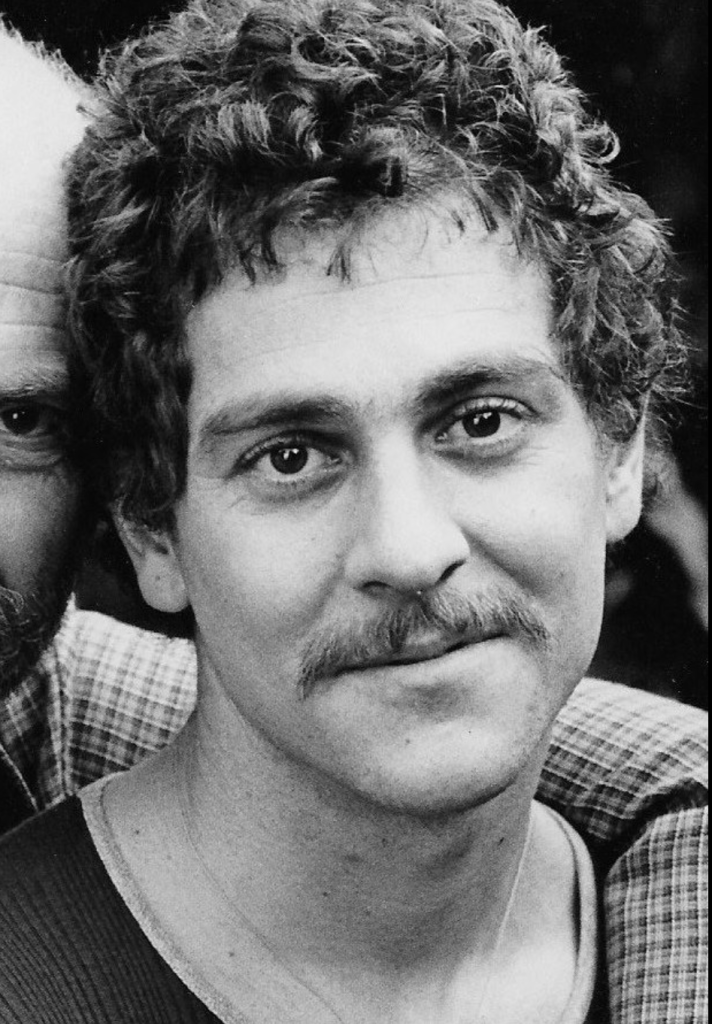

Not only has he made it past 30, but all the way to 74. Now, he resides in a kitschy home in Silver Lake with his longtime friends, 77-year-old Jim Kelly and 67-year-old Jerry FitzGerald, who splits time between the home and a personal apartment. All three men came out as gay in a pre-Stonewall America, and have since watched from the front row as gay rights have leapt forward over the decades. Throughout the heyday of gay liberation, they fought, partied, cried, loved, lost and ended up here.

Now, the trio enjoys a quieter life. They pass their days with their two poodles, Kento and Horgos, curled up around them, and they find fulfillment in music, dance, gardening, poetry and cooking. All three of them are single, but together they form a loving family home. With little example to follow, Kelly — like Beard — never imagined making it to this point when he was younger.

“When I was growing up, my dad, who was not at all accepting of my homosexuality, used to point out gay people and say, ‘There’s only three places you can end up: that’s in the jail, the nuthouse or in the gutter. And I’ve been all those places, actually,” Kelly said, chuckling. “But I did elude those fates for the most part, as ultimate fates.”

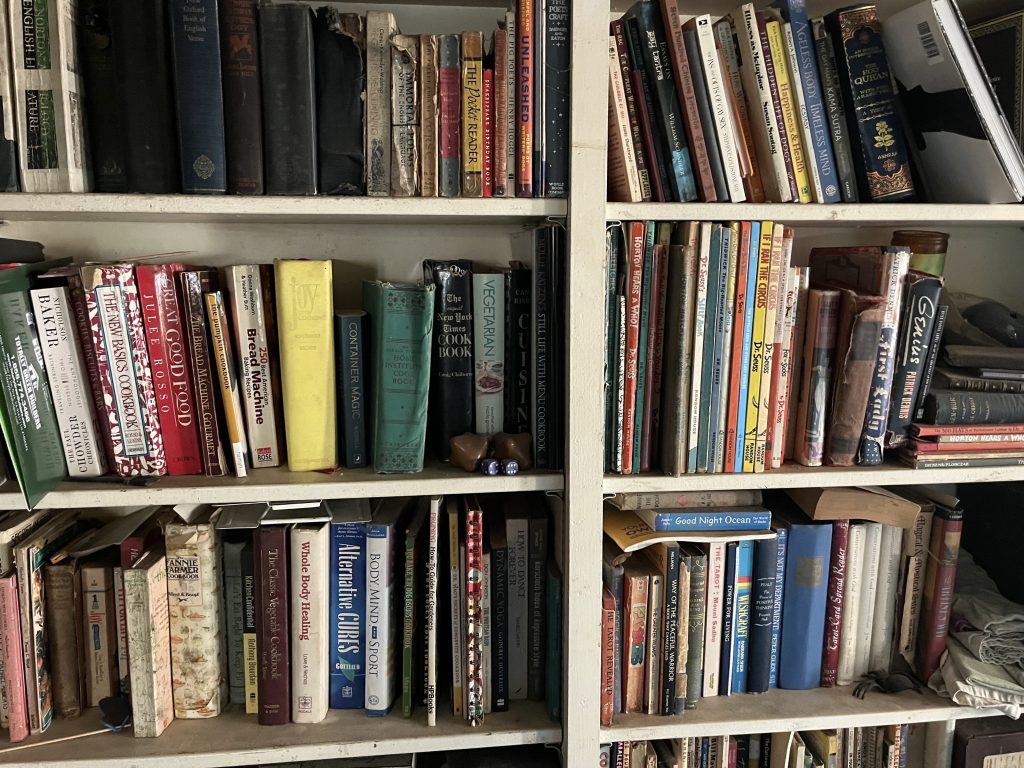

Kelly has owned this house since 1992. Stuffed full of artwork, books and other memorabilia accumulated throughout these men’s lives, the eclectic home is bursting with stories waiting to be retold. Each trinket carries a unique history and emotional significance of its own, which the trio can eagerly and encyclopedically recite on command.

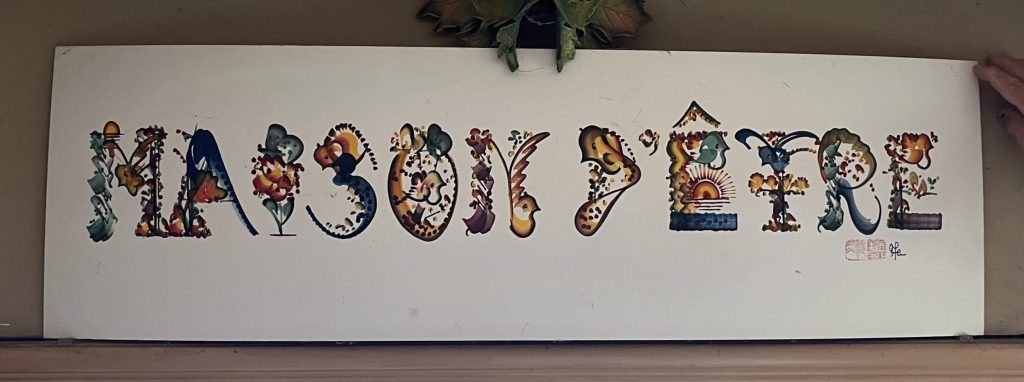

They call the house — and their collective, because the two are inseparable — “Maison d’Être,” a play on the French “raison d’être,” meaning “reason to be,” and “maison,” meaning house. To Kelly, Maison d’Être, its inhabitants and the group of friends who orbit it are his purpose.

“I own the house outright, own the automobiles, pay the taxes, pay the utilities and keep the life going,” Kelly said. “My friends are welcome to live here because I love them, and they are my family. And I take care of them because they take care of me too.”

Getting old isn’t easy for anyone. In addition to physical deterioration, aging brings complex mental challenges — most prominently social isolation and loneliness. For gay older adults, the typical trials of aging can be heightened by a number of factors.

Although the U.S. census has never attempted to measure it, reports estimate that there are currently around 3 million LGBTQ adults over age 50 living in America, with that number expected to grow to around 7 million by 2030. According to a report from Services & Advocacy for GLBT Elders (SAGE), LGBTQ older adults are twice as likely to live alone, twice as likely to be single, and three to four times less likely to have children than heterosexual older adults.

“My friends are welcome to live here because I love them, and they are my family.”

– Jim Kelly

A 2011 U.S. national health survey focusing on LGBTQ older adults found that 59% of LGBTQ older people felt a lack of companionship, and 53% felt isolated from others. In comparison, a 2018 national survey conducted by AARP found that about one-third of Americans over the age of 45 were lonely.

Research has shown that loneliness and isolation are associated with poor physical health, with some experts equating the health risks of prolonged isolation to those of smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

However, Dr. David Camacho, a scholar in gerontology whose published research focuses on adverse effects of aging on minoritized older adults, said that isolation does not always constitute loneliness, and that a few relationships can go a long way.

“It’s not about the number of family members, it’s about the quality of family members. So [older adults] don’t need 20,000 relationships, they may only need one,” Camacho said.

Explore Maison d’Être

Maison d’Être is dressed head-to-toe in decor, mostly artwork sourced from friends throughout the years. A number of decorative themes run throughout the house including undersea creatures, Buddhas and lizards. How many can you spot?

Click around to take a closer look, turn your volume up for audio clips and make sure to step into the backyard!

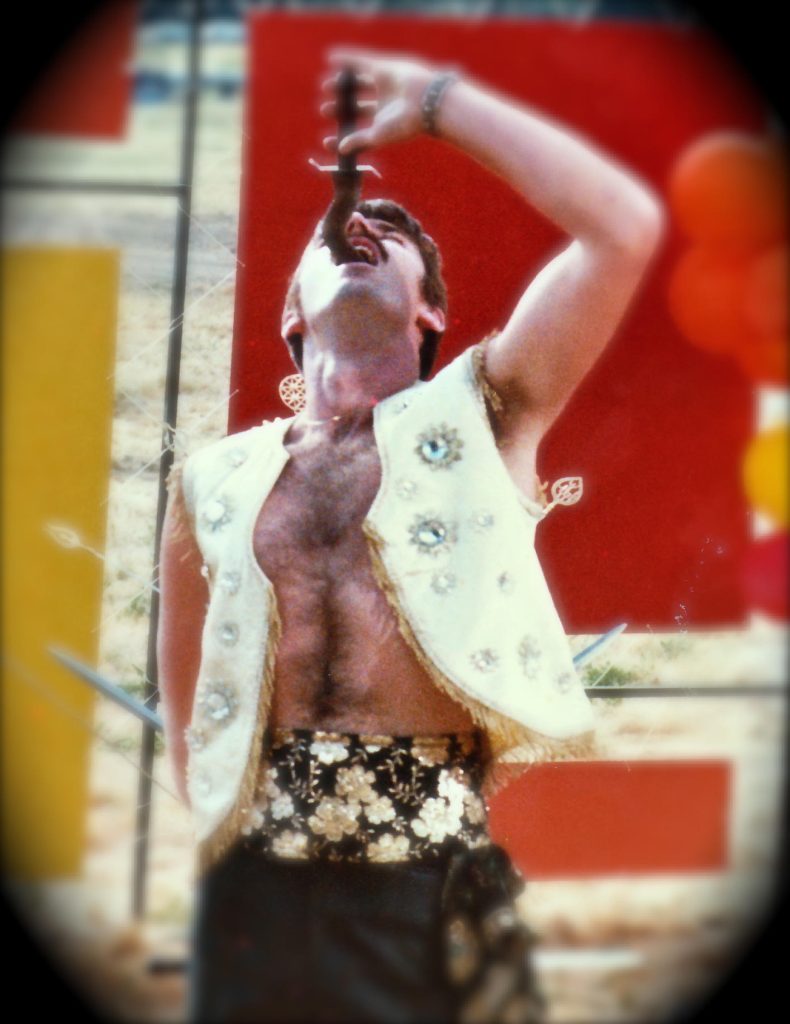

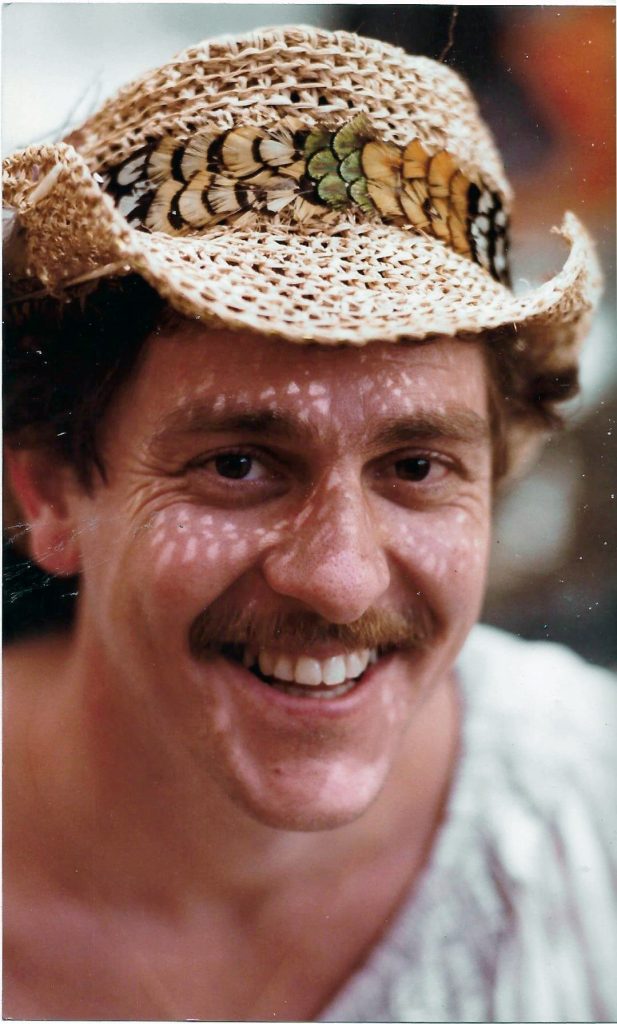

Although the men of Maison d’Être spend most of their time in each other’s company, their social life doesn’t end there. All three men have been heavily involved in the local Renaissance Pleasure Faire for decades and belong to a tangential social group called the Fools Guild, a well-established cohort of Renaissance Faire royalty that hosts parties a few times a year.

“This is really a party household in a lot of ways,” Beard said. “We have a guild that’s all about parties — not so much now as it used to be — but big parties, and the fairs that I do and all that. So there’s a lot of chances to go out and be social, and I’m always the one to be happy to be the dog sitter.”

Because gay culture is so heavily centered around nightlife, sex and youth in general, it can be difficult for some gay elders to maintain a sense of connection to the wider LGBTQ community. Beard said that while he’s tried before to participate in social events at the Los Angeles LGBT Center, which hosts programs specifically to foster community among LGBTQ seniors, it made him felt “alienated.” Instead, he prefers to stay connected through a “small set of friends that are dear to” him, and through the internet.

“I don’t go to the bars. I’m not much of a drinker. I didn’t even when they were around, and they aren’t around so much now except the west side. And so, the culture [isn’t] ‘me’ so much anymore,” Beard said. “Although, I follow it socially. I lurk everywhere online. So I’m rooting for ’em out there. But I feel like the torch just kind of ought to be passed.”

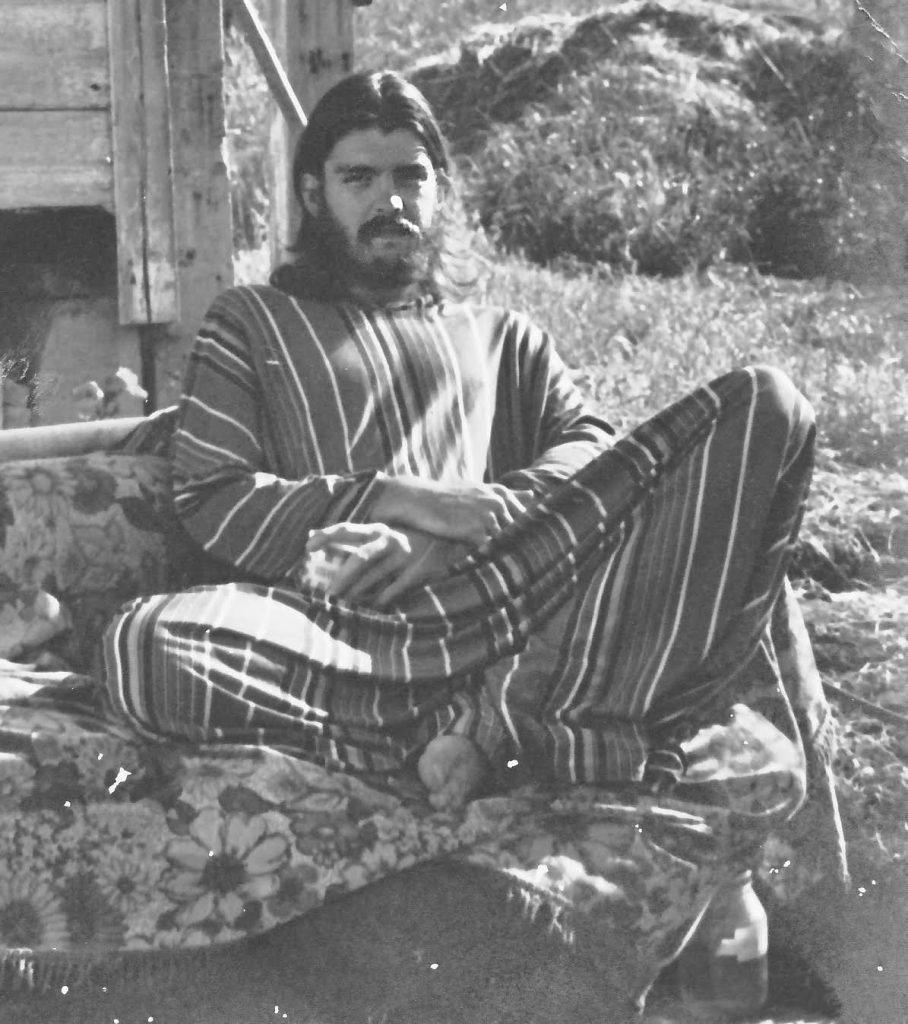

Although the trio’s wild days are largely behind them, Kelly is still sexually active and says many of his peers are too. Kelly has long been very open about his sex life: just ask the detailed sexual calendar he kept during the late 70s, which is now housed at the USC ONE Archives and The Human Sexuality Collection at Cornell University (Kelly’s alma mater). When asked to describe the experience of pursuing sex as an older adult, Kelly opted for a cheeky analogy, referencing a conversation he had with his late friend who was a Broadway actor throughout his life.

“[My friend] said he would show up in casting, and there would be fewer and fewer and fewer actors up for the same roles he was up for. But they would all be really good at it,” Kelly said. “Because if they’d lasted that long… There was fewer of them, but the competition was just as fierce, if not worse. So that’s how I feel about it. There’s fewer of us, but we’re all really good at it.”

Although Maison d’Être seems a peaceful haven now, things haven’t always been that way. Each man that lives here shoulders his own history of dashed hopes, lost loves and hard times. FitzGerald came to Maison d’Être during a particularly desperate time.

A Navy veteran, FitzGerald’s time in service was bookended by crisis: at 19 years old, he ran away from his hometown of Denver to enlist after impregnating his then-girlfriend, having a falling-out with his family and losing nearly everything. He had his first brushes with gay life right before serving and spent his time as a Navyman moonlighting as a waiter at a gay bar. Less than three years into his service, his side gig was discovered and he was honorably discharged on grounds of his homosexuality.

Burdened by the humiliation of being discharged and the guilt of leaving his family, ex-girlfriend and child behind, FitzGerald fell into drug and alcohol addiction: a lifestyle he says he carried on for roughly 35 years. He met Kelly at a dance class in 1998, and they eventually began seeing each other.

“I didn’t even know myself at that time, what I would need to be happy instead of drugs and alcohol because they weren’t making me happy anymore. I had to find happy, and Jim was the beginning of that,” FitzGerald said. “Unfortunately, I put him through hell, too. Because I was still addicted… [Our friends] kept telling him, ‘Kick him to the curb. Get rid of him.’ But he wouldn’t. He didn’t. And I’m so grateful. So grateful for that.”

Even after their relationship turned platonic, FitzGerald continued to live on Kelly’s couch for about five years, still ensnared by addiction. It wasn’t until FitzGerald wrecked a truck bought for him by Kelly as a gesture of encouragement that he was forced to face his addiction from a hospital bed and finally get clean. Now, FitzGerald is nine years sober and taking classes in nutritional science.

“I’m blessed now just to be sober, to be happier, just to be lucky as I see so many friends and so many other people across my journey that have not woken up, have not made it. Plus, I’m over 30 years HIV-positive… just the fact that I’ve survived that too,” FitzGerald said. “I never even thought about getting old.”

I had to find happy, and Jim was the beginning of that.

– Jerry FitzGerald

Kelly refers to FitzGerald as “the prodigal,” commending the way in which he reclaimed his life. According to him, the rough period that they shared brought them even closer. Now, they call each other BFF (as Kelly pronounces it, ‘buh-fuh-fuh’), and they try to start every morning at Maison d’Être with a musical ritual.

“A couple of years ago, Jerry said to me ‘Jim, I can’t get my day going until I hear that Bach minuet.’ And so I said, ‘Well, I’ll play for you every day.’ So I play for him every day,” Kelly said.

Listen to the Bach minuet, Kelly-style:

Like FitzGerald, Kelly is also living with HIV. Thanks to modern medicine, it’s now possible to live a perfectly healthy life while HIV-positive, and even to get to a point where the virus is undetectable and untransmittable. Although FitzGerald and Kelly made it out the other side of the AIDS epidemic, they are two of the lucky ones: between 1981 and 2000, AIDS claimed the lives of nearly half a million Americans and ravaged the gay community.

“AIDs came along, and Richard and I lost our two closest friends the same week. So many people died so quickly,” Kelly said, his voice cracking.

Particularly devastating to Kelly was the loss of his late partner, Jim Layne. Known lovingly by friends as “Jim and Jim” or “The Jims,” the pair purchased Maison d’Être together after being together for 12 years. Kelly still proclaims Layne the love of his life without hesitation, despite having had other relationships since. Six years after they bought the home together, Layne passed away from AIDS.

“His last night on Earth, we just lay awake and said, ‘You’ve enriched my life every day. All the time I’ve been with you, I’m a happier, better person. Thank you for everything you are to me and thank you for being in my life.’ He died the next day. We knew he was sick. It wasn’t completely a surprise, but it was a surprise. But we had a good time together to the very end. The last thing he ever saw was, before his eyes closed, me smiling at him through tears,” Kelly said.

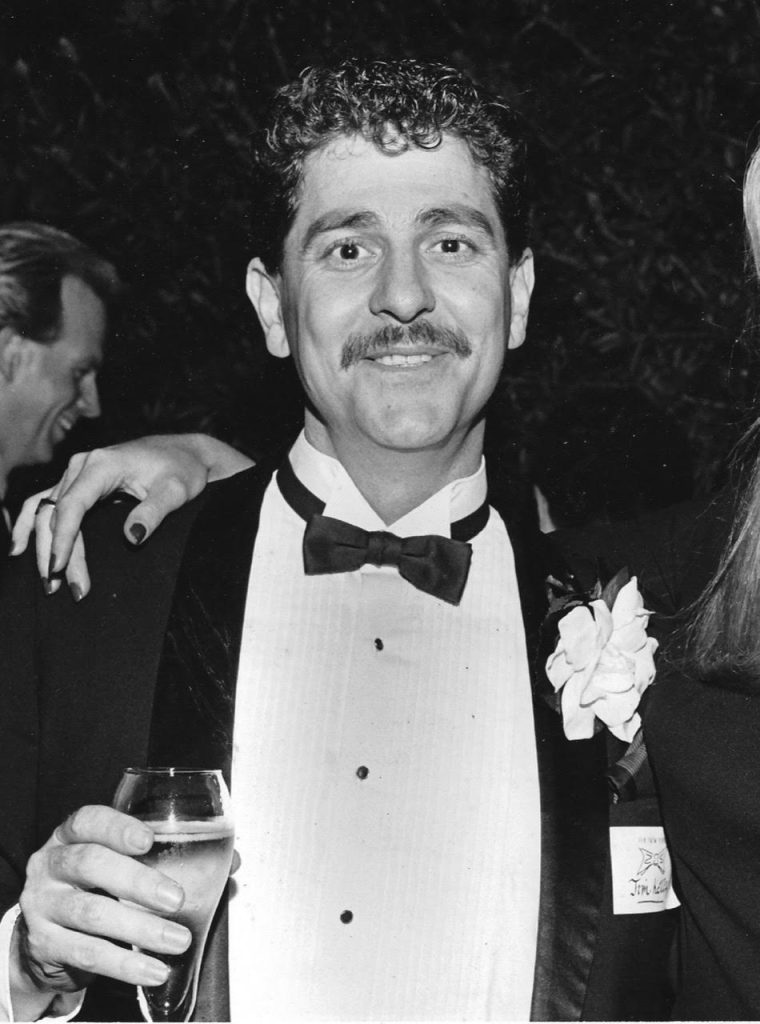

Jim Kelly and the late Jim Layne at their coronation as 13th King of Fools.

Every year, the Fools Guild appoints a new King of Fools at the Renaissance Faire. The Jims were the Guild’s first gay kings and the first binary kingship.

Layne’s passing left an insatiable void in Kelly’s life and home alike. Over the years, however, with the addition of Beard and FitzGerald, Kelly brought love — albeit, a different kind of love — back into Maison d’Être.

Despite the political and personal obstacles that Beard, FitzGerald, Kelly and all their LGBTQ peers have fought against across their lives, they reject the narrative of victimhood so often imposed upon them. Instead they march on, finding the purpose and beauty in their everyday lives and helping each other to do the same.

“I think the stereotype of a bitter old queen or an aging gay man with no friends, or dying alone in the garret, or an Oscar Wilde abandoned by everyone, I think those need to be contradicted,” Kelly said. “Because in my circle of friends, we are happy people who are fulfilled in life and have loving, supportive relationships and are responsible for one another. We don’t have children, so we had better make good friends.”

Naked Youth

A poem by Jim Kelly

July 24th, 2016

It never really went away

the Magic of my youth

no matter that my beard is gray,

I’ve ever sought the Truth,

danced and prayed

writ and played…

and found it oft, forsooth!

As I come into mine own

I find my Magic hasn’t flown

but still abides in recess deep

and so as ever, I shall keep

my search for Truth as best I can,

for thus shall I become a Man.

Become the Man I’ve always been,

who in my youth was sometimes seen

dancing naked in the glen

with wild abandon, fancy free!

I look at him and yet see me,

I have not changed at all since then,

I’m dancing still and shall again

although next time, I must confess…

mayhap I’ll wear some clothes, I guess.

Audio Epilogue: An Endless Well of Stories

The men of Maison d’Être represent just one example of what gay aging can look like.

Across LA, gay and lesbian older adults are adapting to old age in their own unique ways. Listen for some additional testimonies from Carolyn Weathers (84), Wes Joe (70) and Robin Tyler (82) that shed light on their personal experiences and philosophies related to going gray while being gay.

This story is dedicated to all the LGBTQ people who never got to experience the joys of their later lives.

Thank you all for allowing me to stand on your shoulders. – FC