From Decades to Days:

Unraveling Gen-Z's Micro-Trend Obsession

by Kate Hammond

From ballet-core to cottage-core to quiet luxury, fashion’s trend cycle seems nearly impossible to keep up with.

Micro-trends, characterized by their rapid ascent and departure within the fashion cycle, last anywhere from mere days to weeks. Particularly among Gen-Z consumers, these shifts significantly influence purchasing behavior, driven by a desire for social inclusion among peers. As these trends gain traction, we are witnessing long and short-term effects on consumption habits and fashion production.

“Fashion is about constant change. It’s about novelty,” says Professor Alison Trope, a Clinical Professor of Communication at USC, who teaches the Fashion, Media and Culture class at USC Annenberg. “We kind of want to think about that as something that’s always driven fashion, this kind of notion that there are new cycles…at the same time, as you’re pointing out, the cycles are going much more quickly than they used to.”

However, fashion trend cycles are not a new concept. The rise of capitalism in the 14th century and the marketplace drove new fashion changes and trends, as new products would be released with the seasons to encourage people to buy.

The increased pace of the trend cycles can be looked at from two contributing factors, the largest being social media.

“The fashion seasons used to run seasonally. There was fall and winter, and then there’s spring and summer… but we’ve lost that completely,” says Simone Brown, former President of the Fashion Industry Association at USC. “A micro-trend, in my eyes, comes from influencers. Someone wears a dress, and then because it’s trending, everybody else wants it, but they can’t afford it necessarily.”

“So then, of course, you have Zara and Shein and all of these other fast fashions making it. But then once everybody has it, no one wants to wear it anymore, and then it ends up in a landfill or in Goodwill or something,” Brown says.

Hannah Detwiler, the social media manager at Locker, a shopping app that allows users to curate collections of clothes with attached links, says she sees micro-trends all over the app.

“I genuinely feel like since TikTok, the amount of consumption that all of us do on a daily is crazy,” says Detwiler.

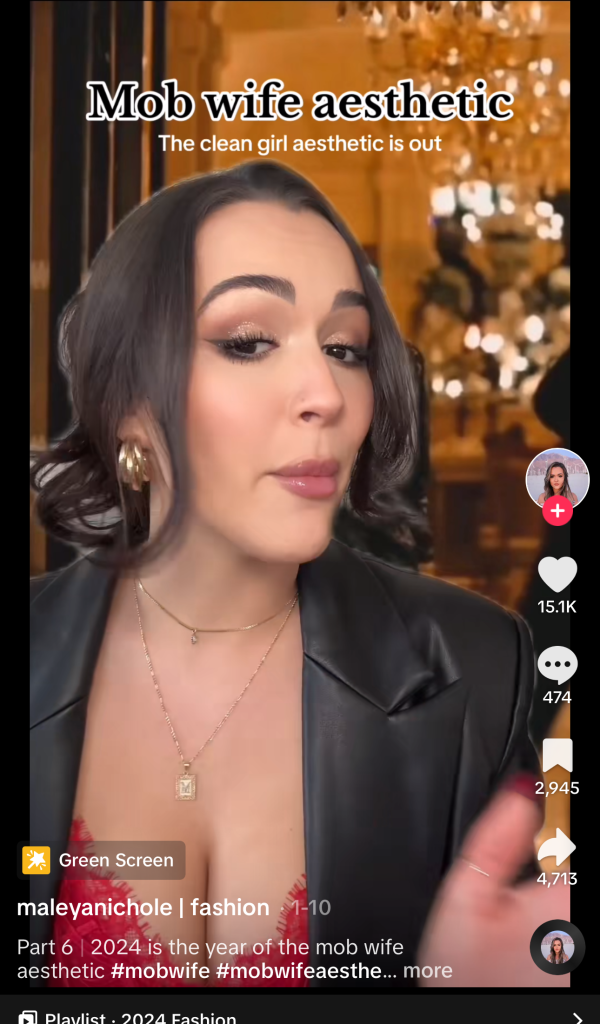

Specifically within TikTok, the short videos allow for high visibility on videos that result in high circulation. Within days of 2024, influencers declared the “clean-girl” was out and the “mob wife” aesthetic was in. Outlets such as the New York Times, Elle, and Harpers BAZAAR even detailed this shift in aesthetic. Even Francis Ford Coppola, director of The Godfather, posted an Instagram post comparing the TikTok trend to that of the character Connie Corleone.

During TikTok’s early days, the platform focused on dancing and singing, yet consumer users changed their focus towards beauty and fashion in 2023. With the hashtag #OOTD garnering over 170.5 billion views, the platform has become a birthplace for all micro-trends.

“But the question is, is this really an aesthetic? Is this really something new? Or is it just someone putting a label on something, and the label becomes something hashtag-able that can travel and circulate through social media in a particular way,” Trope says.

The second factor is whether something is coming from the top (designers, companies, trend forecasters) of the fashion industry or the bottom (consumers). For example, are the brands and trend forecasters pushing aesthetics on consumers, or is it the other way around?

The traditional top-to-bottom cycle is most clearly illustrated in a scene from the movie “The Devil Wears Prada.” In an infamous scene from the film, Andy is asked by her boss, Miranda, about her sweater. Miranda explains that Andy’s seemingly insignificant choice of clothing stems from a series of decisions made by high-profile fashion designers, fashion houses, and magazine editors, like herself. She educates Andy on how the cerulean blue sweater she’s wearing was likely a result of collections from designers like Oscar de la Renta and Yves Saint Laurent, which eventually trickled down through the fashion industry to reach a mass-market store where Andy likely purchased it without realizing its origins.

Nowadays, with the top-down system depicted in the film, the fashion industry is experiencing a shift towards micro-trend cycles, which are more bottom-up. These micro-trends often emerge from social media and niche communities rather than being dictated by high-profile designers or fashion houses. Individuals, influencers, and small brands play a significant role in shaping these trends through their online presence and interactions.

Brands are even seeing consumers tap into TikTok and Instagram more than runway shows for their latest fashion inspiration. According to Newby Hands, a contributing global beauty director at Net-a-Porter, 80% of customers say that they are “extremely likely” to buy a beauty product after seeing it on social media.

“There’s a bit of a gap in understanding fashion. I think the way that people are approaching fashion now is in terms of trends and belonging and dupes…but not necessarily fashion, right?” says Haydn Phillips, a fashion writer for the Daily Trojan. “Fashion is art, it’s history, it’s effort, it’s time, and it’s people and what they do to represent these brands.”

Despite the initial cause of micro-trends, one thing remains constant among the Gen-Z individuals who are following these trends: the need for belonging.

“I see micro-trends a lot as is like FOMO of someone’s wearing this thing that you really want to be a part of. So, you rush headfirst into it without deciding whether or not that’s your style,” Brown says.

Fashion has always been a way to express yourself to the world. As a form of identity, clothing helps situate yourself – whether that be as a student, employee, sister, or friend. The idea of continually buying into these micro-trends can disrupt and challenge the notion of “personal style.”

Let’s take the trend of “quiet luxury.” This aesthetic became extremely popular in the summer of 2023. As shown in the graph above, there was a huge spike in Google search interest in “quiet luxury” in June. With events such as Sofia Richie’s French wedding and Gwyneth Paltrow’s ski trial, people became obsessed with minimalist and refined designs. However, the timeless and sophisticated pieces that Richie and Paltrow styled are nowhere near cheap. As a result, fast fashion companies immediately rushed to put out dupes of high-end clothes.

Detwiler saw first-hand how much consumers obsessed over this trend.

“It was our highest engaged post and, for months, people were obsessed with all of [Sofia Richie’s] looks that we were thousands of dollars,” Detwiler said. “Personally, you know, a recent college grad would never, ever buy those pieces so then we started doing lookalikes for less.”

Micro-trends thrive on the fast-paced, fast production cycles that fuel fast fashion companies. We always have to think of production and consumption as two sides of the same coin – are these fast fashion companies pushing the trends? Or are they responding to them?

Fast fashion’s negative impact on the environment and labor practices is not new but has continually gotten worse with the emergence of micro-trends and dupes. Fast fashion companies are producing twice the amount of clothes today than in 2000. This dramatic increase in production has had a tremendous impact on waste. The average U.S. consumer throws out 81.5 pounds of clothes each year, and the number of times a garment is worn has declined by about 36% in the last 15 years.

“It’s not just about the production of clothes. It’s also textile production and water contamination,” Brown says, “The only way to really be sustainable with your clothing is not to buy.”

“Everybody, in this day and age, wants to be an influencer…so everyone feels like they must stay on top of all the trends. As you said, they’re buying the Zara version or the fast fashion version [of the trend], just so they can like posting it and like put it on TikTok and Instagram,” Detwiler says.

With trends continually emerging and disappearing, there is no end in sight for the micro-trend obsession. However, there are some practical and legislative things that we can look at to help challenge our consumption habits.

“I think that the fast fashion companies will continue to go along as they have been because there’s nothing stopping them. Oil and gas companies have specific regulations and taxes on them because of the environmental damage that they cause, but the fashion industry is one of the top five polluters and no one’s ever heard that…they just think of oil and gas,” Brown says.

We can also look at our shopping habits. Rather than focusing on the quantity of items, focus on the quality. What if instead of buying a dozen cheap shirts, you invested that same amount of money into a nice jacket that will last you forever? When Detwiler shops, she asks herself, “is this something that is classic and my grandkids will want to wear if I handed it down to them?”

Without significant shifts in our consumption habits and legislative action, the cycle of micro-trends and micro-seasons shows no signs of slowing down. The relentless pace of production and consumption creates a culture of disposability, resulting in environmental degradation. Only through concerted efforts to promote ethical practices, reduce waste, and foster greater transparency can we steer the fashion industry toward a more sustainable future.

is proudly powered by WordPress