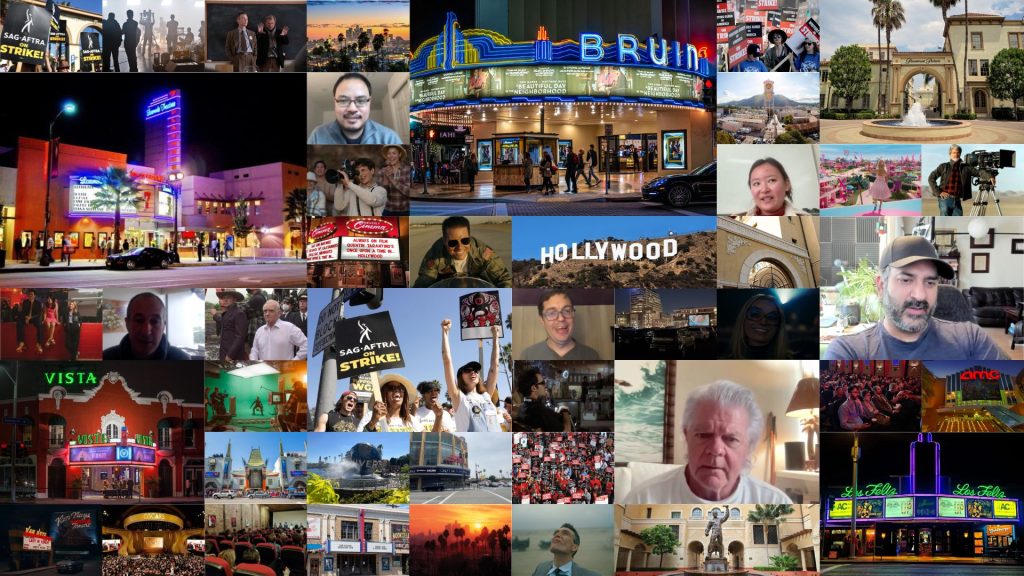

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood:

Cinema at a Precipice

With the doom and gloom surrounding the industry, is there reason to be optimistic about the future of film?

By Matthew Andrade

After a year where one film crossed one billion dollars at the box office and another came dangerously close to that mark, how can one be cynical about the future of cinema?

Yet, that dichotomy — that contradiction — defines the current state of film. Great films are being released and one of the great movie theater phenomenons of all time, “Barbenheimer,” happened just months ago. Still, the future of the industry is described by many as uncertain at best.

The longest strike in Hollywood history

Nearly a year ago, collective action from one of the largest unions in the country flipped the film industry on its head. On July 14, 2023, SAG-AFTRA, the acting and entertainment union representing approximately 160,000 people, voted to go on strike after the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers refused to accept the union’s proposed contract.

According to Shaan Sharma, a member of the SAG-AFTRA negotiating committee, the union had five key demands: higher wages, create a residual model for streaming services, increase contributions to pension and health funds, improve conditions of self tapes and strengthen protections against artificial intelligence.

The strike was the longest in Hollywood history, lasting 118 days in total. It ended on Nov. 9 after a tentative deal was reached the day before. On Dec. 5, 78% of members voted to ratify the contract.

However, Sharma was not one of the union members who voted to approve the contract.

“My general feeling is that we didn’t accomplish what we set out to accomplish,” Sharma said. “In trying to do so, we made compromises that actually cause more damage than the good that we achieved.”

In Sharma’s opinion, the contract did not fully meet any of the aforementioned five key demands. In particular, it fell significantly short with its impact on wages, streaming residuals and artificial intelligence protections.

In terms of wages, the contract only increased minimum pay by 7%, 3% less than would be necessary to keep up with inflation. SAG-AFTRA touted this increase as a “win” since the Writers’ Guild and Directors’ Guild only achieved a 5% increase in their most recent contracts. Regardless, Sharma doesn’t believe that the negotiating committee achieved its goal of adequately increasing base pay for its members.

As for the contract’s provisions regarding streaming services, Sharma also believes that the conditions did not go far enough in securing a fair share of streaming revenue for SAG-AFTRA members. The contract lays groundwork for streaming services to pay actors a “streaming bonus” of up to a total of $40 million per year.

There’s a catch though, Sharma says. Streaming services are only required to pay out streaming residuals to actors on movies or TV shows that are watched by at least 20% of the service’s domestic subscribers within the first 90 days of the content being on the platform. The contract doesn’t allow for movies and TV shows that were not made for streaming to qualify for this bonus, either. Though the SAG-AFTRA contract was lauded as a billion-dollar deal, Sharma fears that streaming services will find ways to prevent content from reaching the necessary streaming bonus threshold.

“$120 million of that [$1 billion] is in a theoretical streaming bonus that hasn’t been set up yet, that we don’t know how it’s going to work,” Sharma said. “We don’t know how many shows are going to qualify … It’s possible that not a single show will ever qualify for that streaming bonus, which means that $120 million will never appear.”

Sharma’s other major qualm with the deal is its lack of protections against emerging artificial intelligence. The contract allows for A.I.-generated actors to be used in movies and TV shows, with only a few exceptions. For example, A.I. can be used to generate background actors once a minimum number of human background actors are hired. A.I. actors can also only be used if they do not directly copy a physical feature of a human actor. This means an actor would have to notice their own eyes, ears, nose or other body part in the makeup of a computer-generated actor. Sharma doesn’t believe this language is specific enough to provide sufficient guardrails against the continuing rise of artificial intelligence.

“We’re actually seeing artificial intelligence come for our work ahead of schedule,” Sharma said. “So it was very important that we secure as powerful of protections against that as possible during this negotiation. There are those that will say we achieved a solid first step in that direction, and then there are those that will say we left such gaping holes as to make our union incredibly vulnerable.”

SAG-AFTRA’s ratified contract with the AMPTP lasts for just three years. At that point, the union’s members will have to decide whether to accept the AMPTP’s offer or to go on strike once again. It’s uncertain whether the union will need to go on strike in 2026, or whether the industry can even withstand another prolonged work stoppage so soon after the last one.

“What leverage will we have in three years? Will our membership be willing to strike again in three years if necessary?” Sharma said. “Will they have the will, the strength and the solidarity to do that? Will the rest of the industry support us going on strike in three years if necessary? Because if the answer is no, then we don’t have leverage to fight for the things that we couldn’t get this time when we were on strike.”

Movie Theaters: “The reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated”

Much has been said about the supposed “downfall” of the movie theater industry. Ticket sales have been on a steady decline since 2002, according to the MPAA, though a recent emerging trend is perhaps even more frightening: From 2018 to 2023, movie theater attendance was cut in half, per IndieWire.

Still, new theaters have popped up in Los Angeles in the last few years. Laemmle Theatres, a staple of the city’s moviegoing since 1938, opened its eighth location in 2021: the Laemmle Newhall in Santa Clarita. Greg Laemmle, President of the movie exhibition company, acknowledges the challenges movie theaters are facing, but he doesn’t see the movie theater industry going away any time soon. Laemmle doesn’t believe streaming is even the main challenge to theaters nowadays, as many suspect.

“I think the easy answer is to just say, ‘Oh, it’s streaming.’ And I just don’t think that’s accurate,” Laemmle said. “Some of our bigger successes are films like [Netflix’s] “Maestro,” which did a lot of business in art houses … Given the appropriate opportunity and the appropriate film, audiences are definitely wanting and showing that they want to see these films in movie theaters.”

So, what is the main challenge theaters are facing? According to Laemmle, it’s the lack of variety of films in theaters. While 2023’s summer blockbusters, “Oppenheimer” and “Barbie,” became two of the highest grossing films of all time, smaller releases that have been the backbone of the movie theater industry since its beginnings aren’t being produced at as high of a rate as they once were. Laemmle cited rom-coms and family films, two genres that often perform well at the box office, as being noticeably absent.

“I think ultimately what’s important or what’s necessary is that there’s a film every four to six weeks for each audience segment,” Laemmle said. “Right now, it’s more like every four to six months.”

Across town, in the Toy District of downtown Los Angeles, stands a movie theater that operates completely differently than the Laemmle or traditional movie theaters. The Secret Movie Club, founded by Craig Hammill in 2016, screens almost exclusively older films — films that are, for the most part, available on streaming services.

With this model, Hammill and his small team have had to innovate more than most theaters in order to get people to show up. Instead of strictly functioning as a movie theater, Secret Movie Club has evolved into a hub for movie lovers, hosting everything from film-related parties and festivals to filmmaking workshops and open-mic nights.

“Secret Movie Club, just organically, is developing a new kind of model,” Hammill said. “For us, it’s what can we offer that you absolutely can’t get at home?”

When it comes to programming Secret Movie Club’s screenings, Hammill has followed Laemmle’s belief that a wide variety rules the day. Recently, Hammill has noticed that anime titles and international films have done surprisingly well in attracting new audiences, with “Neon Genesis Evangelion” and Edward Yang’s “A Brighter Summer Day” playing to sold-out crowds. To Hammill, giving the audience something unique is key.

“You have to do things that excite people that don’t get programmed a lot, but have an integrity to them. Like people will go, ‘Oh, I know why they programmed that,’” Hammill said. “So sometimes you program something because you feel like it’s the right thing to do and you’re ready to take a hit because only 10 or 20 people are going to show, and you sell out.”

Though Hammill and Laemmle function under very different business models, they both agree that raising prices isn’t the answer to rejuvenating the movie theater industry. According to the National Association of Theater Owners, movie ticket prices rose by over 62% in the 20 years between 2002 and 2022, a rate nearly 12% faster than the rise in inflation during the same time period. Laemmle and Hammill both maintain that they’re committed to keeping their prices affordable.

“If we are developing a community of people that are going to regularly go to the movies several times a month, not just several times a year, then price point is an important component to that,” Laemmle said. “While we’re not necessarily a complete bargain house, there are bargain opportunities for people so that they can enjoy movies more frequently.”

“I have a mentor who always tells me, ‘Don’t kill the goose that lays the golden eggs,’” Hammill said. “What he means by that, as I understand it, is understand what drives people to the movie theaters and don’t kill that … So as long as we’re all committed to that and not just making money or whatever, we’re going to be fine. But we can’t kill the goose that laid the golden eggs, and maybe some of us need to talk to the goose and get to know the goose again.”

Listen to the audio below to hear about what moviegoers want to see in theaters.

Perspectives from across the film industry

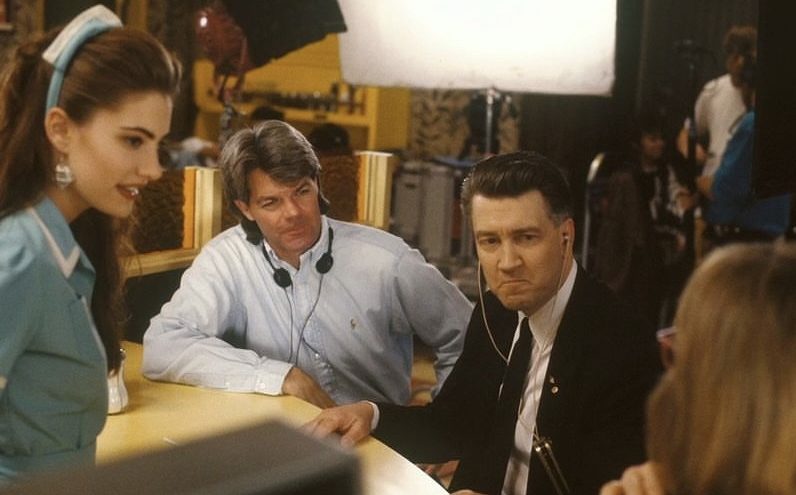

Though the film industry is going through a time of change, this isn’t the first time the industry has been disrupted by similar forces. Duwayne Dunham — an editor on many classic films such as “Return of the Jedi,” “Blue Velvet” and “Wild at Heart” — was a part of what he claims to be one of the biggest transitions in the industry’s history: switching from making films on celluloid film to digital. However, he expects the new technological changes to be monumental.

“I’ve seen a lot of changes,” Dunham said, “but I don’t think I’ve seen anything quite like what may be coming.”

Dunham, of course, is referring to artificial intelligence. Dunham doesn’t see the general concept of A.I. as anything incredibly novel — he recalls director George Lucas talking about the potential use of A.I. in production in the late 1970s, though he didn’t call it A.I. back then — but Dunham believes that A.I. will be able to help editors put together films more efficiently. It will give editors more creative freedom since the small monotonous tasks of editing will be handled.

“It’s just a tool,” Dunham said. “I don’t fear it’s going to replace creativity … The input is what’s important because A.I. doesn’t know anything other than the data input.”

Despite the possibility of A.I. eliminating so many jobs in the film industry, Dunham argues there may be even more potential work for young filmmakers than there has ever been. He mainly credits this to the accessibility of technology and the advent of streaming services.

“I think that there are more opportunities today with the number of streamers that are out there that need content,” Dunham said. “I think there’s more opportunity for a series, not so much a standalone theatrical release. That’s becoming a small fraternity.”

A USC film student trying to break into the industry, Valerie Fang, has a similar perspective. She sees the value in streaming platforms being able to introduce people to a wide variety of films.

“I love streaming platforms because I grew up in Shanghai, China, and I think, in China, people were developing streaming platforms before streaming platforms became such a big thing in the United States,” Fang said. “So I grew up with this idea that you can stream films on your phone or on your laptops or whatever. I think it makes film-watching a more enjoyable and more accessible experience for a lot of people.”

When it comes to streaming services, New Yorker magazine film critic Justin Chang feels they do some good but a lot more harm. He’s “grateful” streaming services have provided budgets to films that otherwise may not have been made such as Alfonso Cuarón’s “Roma,” but he also thinks streaming services have hurt legacy movie studios to the point where they’ve become more “risk-averse.” More than that, Chang believes streaming takes away from the power of movies.

“When a movie can live on a physical screen, I am convinced that … if it stays there for weeks or even months and you have to go out and find it, that keeps movies alive,” Chang said. “That is what allows movies to have impact.”

Though each of them have a different stake in the industry and are at different stages in their careers, Fang, Dunham and Chang all share the same sentiment — they’re optimistic about the trajectory of cinema.

“Storytelling and a desire to hear stories, it’s fundamental to us,” Fang said. “So that’s the security of the filmmaking industry.”

“It’s only going to get better and better,” Dunham said. “I believe it can get, if the individual filmmaker wishes it, it’s going to get more immersive for the audience.”

“I saw a lot of really great and really good movies last year,” Chang said, “and that to me is as good a measure of anything as looking at where things are monetarily.”