How leaders in the field are approaching awareness and action to take care of the planet

Li An Phoa, a teacher, ecologist and entrepreneur, says, “The sign of a healthy economy should be a drinkable river. If we have a world with drinkable rivers again, it means all our relations are healthy and in balance.”

Phoa founded Drinkable Rivers, an organization that conducts River Walks. These are expeditions that can be anywhere from one day to a few months long where anyone who signs up comes together to learn about and take care of part of a river. As part of the expedition, you walk alongside the river and take care of it. This can look like collecting samples to test or by talking to people you run into and discussing the river.

There are more than 150,000 rivers in the world, which is why Phoa aims for citizen science for her methods to take care of the river, where anyone around the world can do it without needing too many resources.

One of the many rivers in the world is the Los Angeles River. More than 80 years ago, it was occupied and taken care of by the Gabrielino-Tongva Mission Indians. At that time, the river was surrounded by lush and thick trees with a rich habitat for species such as mountain lions, deer and now-endangered steelhead trout.

The river was known for being dry during the summer and flooding over the winter. The Tongva people adapted to these shifts. However, in the early 19th century, Spanish colonists made their settlements too close to the river banks. There was an enormous rainfall that led to a great flood. It took out 96 people and 1,500 homes.

Due to this event, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was brought into the picture. Over 20 years, starting in 1938, they built a concrete encasement of the river using 3.5 million barrels of cement. Due to the encasement, the river went from being an ecosystem to just a path for water transportation from the mountains to the ocean.

Residents of Los Angeles have put together organizations to restore the habitat and ecosystem of the river. One example is Friends of the Los Angeles River, a nonprofit founded by writer Lewis MacAdams in 1986. They have curriculums to teach about the river, lead community engagement programs and advocate for the river.

Another organization is LA River Arts. This one was founded more recently, in 2014. Jenna Didier was named the executive director in March 2022. They combine actions in “advocacy, public policy, and the arts to re-present the river we share.”

Didier believes that, “The river being encased in concrete was less than 100 years ago. There are still people alive that remember what it was like to swim and fish in the river. We can still get there.”

She comments on Phoa’s belief that the drinkability of rivers is a key performance indicator of a robust economy, saying, “If that can be the new benchmark of where we should be going with capitalism, so much would be solved because everything relates back to water and the landscape, what feeds into our water systems.”

One way to advocate for the health of rivers is by giving them rights. The Māori tribe in New Zealand fought for these for the Whanganui River. Since 2017, when the Māoris won the 140-year fight, the river has been living with the same rights as a legal human being. Now, if someone “abused or harmed” the river “the law sees no differentiation between harming the tribe or harming the river because they are one and the same.”

“If we give waterways full legal rights,” Didier says, “it’s no different from corporations being given personhood. They can’t speak. But guess who can speak for them? Attorneys. So rivers, you know, other waterways, even landforms, could be given legal rights and have their own attorneys who can speak for them.”

Advocacy and education come into the picture to make this happen, and art is a vehicle for doing so. The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) Los Angeles hired Kelsey Shell as its environmental and sustainability strategist in April 2023.

“I think that the emotional component of all of this is overlooked sometimes. We’re all grappling with climate grief and all these different fears and don’t really have a place to put those feelings,” Shell said. “So I think art and culture has a place in that work too.”

Art is a vehicle for storytelling and advocacy, and Didier sees the threat of it as low. She believes because of this, there is more flexibility for what people can create and put out.

“The top echelons of power see us as a very minor, minor, minor influence on culture,” Didier said. “The stakes are very low and so as a result, there’s not a lot of pushback. We can be very experimental and very forthright in our demands and in our work, and in demonstrating how it looks when you bestow equal rights upon a river, when you’re placing the river in the forefront as the lead artist, when you’re doing a creative activity with the river. […] If we can demonstrate that, then pretty soon, it will have an effect that [ripples] through all of the culture and hopefully get to where it needs to be, which is in legislation.”

Didier’s work with LA River Arts is dedicated to restoring the river and to reconnecting the communities that live along the river back to it, “including more than human communities.” Restoring the health of the river, she believes, also means restoring the relationship to the people who originally resided by it.

The work that LA River Arts does is “site-based work,” as described by Didier. She says, “Every time we are doing something, we are walking the river, we’re touching the land, we’re thinking about how to reciprocate with the river. We do these monthly walks called River Sessions.”

A River Session is when a group of volunteers and people who are part of LA River Arts walk by a stretch of the river. They do a different stretch of the river each month. LA River Arts reaches out to organizations that are affiliated with the community that lives by that section of the river in order to involve them. They also reach out to artists affiliated with the organizations and have them be guides for the River Sessions. They do this so that they can see the river through the eyes of the artist and learn their creative practice.

Didier also tries to include “Indigenous culture bearers” in the River Sessions to ground the participants and remind them of the history of and relationship with the river to grow in alignment with that. As a minimum, Didier says, everyone helps pick up trash because, “The easiest and most basic thing that we can do to reciprocate the land and the river is just to simply remove at least some of the waste that we’re generating so it’s not clogging up the place.”

“I’m very proud of this process,” Didier said. “It’s very slow. It hasn’t resulted in any permanent work, but it has resulted in us building relationships with over two dozen different organizations, dozens of different artists, poets, writers, creative practitioners, and of course, Indigenous cultural practitioners.”

In terms of the work that MOCA is doing, Shell explains that their work in sustainability can be divided into two sections: direct impact projects and storytelling. With the direct impact projects, MOCA is working on the decarbonization of buildings, moving away from fossil fuel use, making their waste cycles more sustainable and finding more renewable energy sources for heating and cooling. They are also trying to reuse materials for art projects.

“A major part of my job is really working with everyone to braid sustainability into what they already do as opposed to introducing external projects and initiatives,” Shell said. “It’s really about bringing this thinking into the way this museum already works.”

With storytelling, MOCA creates educational programs for its audiences as well as for its internal staff to learn more about sustainability. It is also creating public programming such as bringing people together to talk about issues, specifically about environmental justice in Los Angeles.

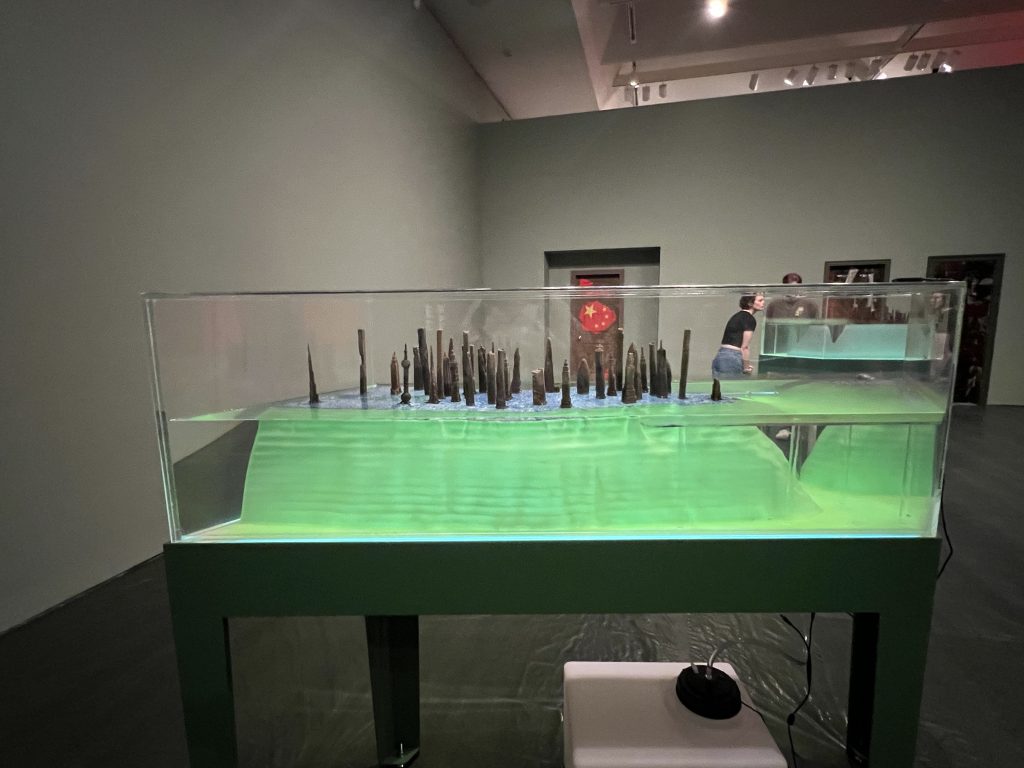

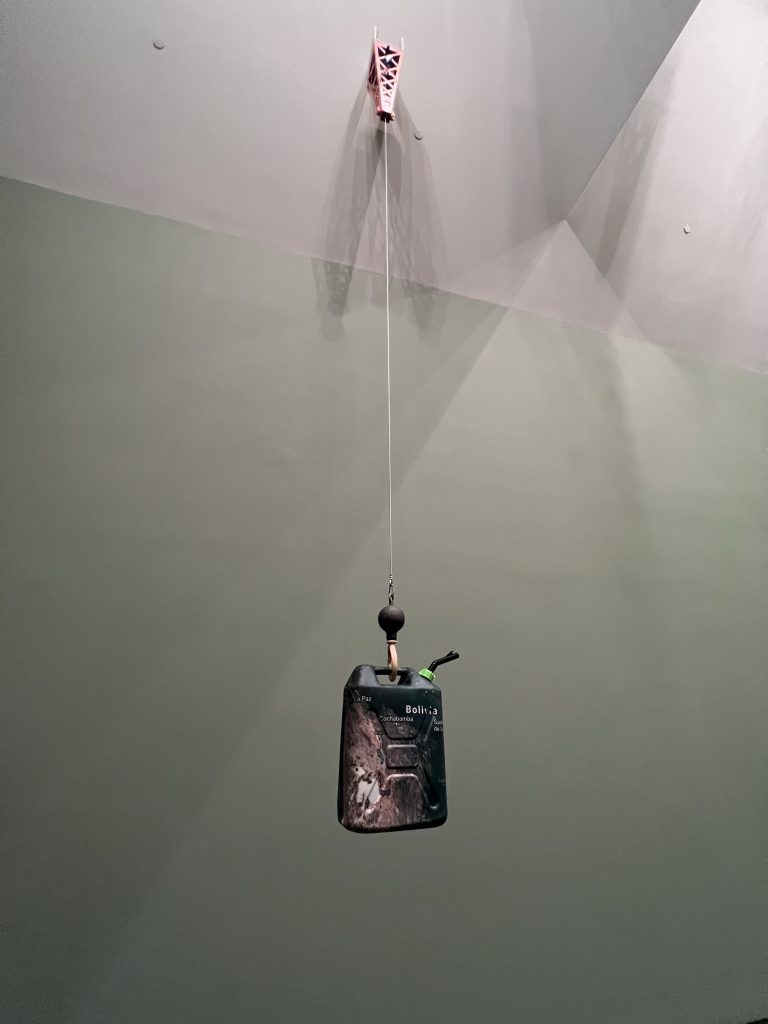

Another way MOCA is using storytelling to move toward sustainability is by inviting artists to tell climate change stories through exhibitions. Most recently, the museum put up artist Josh Kline’s exhibition “Climate Change,” which is an “ambitious, immersive suite of science-fiction installations that imagines a future sculpted by ruinous climate crisis and the ordinary people destined to inhabit it.” The exhibition opened for view on June 23 and will be up until Jan. 5, 2025.

Josh Kline’s “Climate Change” at the Museum of Contemporary Art. (Photos by Shivani Gupta)

Shell calls on artists, galleries and every sector to take action. She encourages artists to join communities such as Artists Commit, where they can work with their galleries to start a Climate Action Plan. Artists also have the ability to work with their galleries to choose their materials and work shipping methods to make them more sustainable. They can also be more sustainable with the materials they use and integrate environmental stories important to them into their work.

In terms of galleries, there is a Gallery Climate Coalition, which is a resource for galleries to decarbonize their spaces and start a green team. There is a free carbon calculator where they can determine their emissions, and overall, it is a good place to start for galleries to become more sustainable.

When speaking to a broader audience, Shell says sustainability is integrated into everything. Rather than being solely a sustainability job, it is more of a sustainability and art or a sustainability and agriculture job, where the two are intertwined. She says it is important to have people who think about those issues and how they intersect with the needs of that sector.