Stories of Adoption — Adoptees

My Family’s Story — Iris

Iris doesn’t really think too much about adoption — at least, her own adoption.

Iris was adopted from Bulgaria almost 29 years ago, and she remembers nothing from her almost two years spent in the orphanage. She’d consider going back to see the country she is originally from, but she has little interest in meeting her birth parents. To Iris, her birth mother is not her mom. And while she’s thankful, her adoption is not something she thinks affects her life.

“I was never really reminded that I was adopted — I feel like sometimes reminding adoptees constantly sort of says ‘well okay, that’s your narrative, that’s your story.” Iris said. “I’m so much more than just being adopted.”

As a transgender woman, when she thinks of adoption, she thinks of what her own future as a mother might look like. She can relate to the woes of potential mothers struggling to conceive; as much as she wishes she’d be able to carry and conceive her own child, that is something that will not be possible for her.

“The chances of having a baby when you’re a trans woman is tougher,” Iris said.

While the chances are lower, she is grateful for alternate family building options other than natural birth, like surrogacy and adoption.

For Iris, it is sometimes hard to hear about the negative stigma around adoption.

“It’s a blessing, it’s another option. Get blood out of the story — it’s a child and you’re going to connect,” Iris said. “it doesn’t matter that if that kid is not biologically yours, because at the end of the day that baby is a part of you.”

Emma Denton

A Facebook group, 1200 dollars Canadian and a woman named Lydia were all Emma Denton needed to find her birth mother.

Anyone who knew Denton knew she always had an “itch” to know more about where she came from. Born in Krasnoyarsk, Russia, in May 1999, her adopted family brought her to Canada in April 2002. She had one photo of her birth mother, but she still remained curious. Where was her biological mother now? Did she have biological siblings? What did they look like?

It was not until the end of her third year of college that she finally decided to go for it. She joined Facebook groups, stumbling upon Russian Adoptee Search Angels, an organization that helps reunite adoptees with their birth parents. She was put into contact with Lydia, a former adoption agent who used to facilitate adoptions between the US and Russia. Lydia now lives in Denton’s birthplace, Krasnoyarsk, and helps reunite families. After Denton paid the fee, Lydia found her birth mother within 48 hours.

“[Lydia] spoke with her and was like, ‘Okay, you have a daughter who lives in Canada. She’s wanting to reach out and talk to you,” Denton said. “At the time, my older brother and sister, who live in Russia, didn’t actually know that our mom had placed me for adoption, so she had to make a decision if she was ready to give up this secret and she chose to do so — Thank god.”

Denton has not met her birth family yet, but she is saving up money to make the trip. In the meantime, she runs a Tik Tok account @Svetty4444 chronicling her story and thoughts and opinions about adoption.

For one, Denton believes that people should only adopt if they have the right intentions, and the bandwidth. For Denton’s parents, because the only reason they adopted was because they wanted a big family, they did not necessarily consider the time and effort it takes to raise an adopted kid.

“When you’re taking on a responsibility of adopting a child, there’s a lot more elements than you wouldn’t necessarily worry about with a biological child — you have to be ready to accept that things will be out of your control, be willing to accept that you may need to provide them with therapy, that they might be more expensive than a biological child.” Denton said.

Ka hee Krause

When Ka Hee Krause was brought from Korea to the United States, she wouldn’t stop crying.

Though at the time unaware of what she was yet to face, she ultimately struggled with being placed in an unfit home, feeling a connection to her birth place and culture, and resentment for her birth mother. Though at the beginning, her parents made an effort to incorporate her roots, it did not last. Growing up in a predominantly white area with a white family, being bullied for her looks, she began to resent her race, pushing away from learning more about her culture in order to fit in.

“In my case, especially because it was an international adoption and my parents were white, they didn’t really go in with the cultural knowledge of where I came from,” Krause said. “My mom was extremely abusive and negligent, my dad was extremely abusive and negligent and my brother was a psychopathic criminal.”

Krause’s biological mother was 17 when Krause was born. Facing the stigma of being a teen mom, her mother quickly gave up her parental rights after her birth and Krause was placed with a foster family for the next six months in Seoul before being adopted.

Krause feels like not everyone adopts for the right reasons. Instead of adopting a child because they genuinely want to raise children and create a family, she feels like sometimes adopted children are treated like trophies. Especially when it comes to white parents adopting a minority child internationally when there are so many children in America who need families.

“Some parents adopt children and are more like, ‘look at how good I can be! Look how amazing I am for providing for this child that otherwise would have nothing!” Krause said. “My parents displayed a very nuclear family, but behind the scenes, my parents really didn’t care.”

Krause had often gone back and forth about her feelings of wanting to meet her birth mother. When she was little, she wanted to meet her birth mother, but when her adoptive parents began to be more abusive, she found herself resenting her. But once she turned 17 herself, she began to understand a little more about where her mother was coming from and why she was given up for adoption.

“I would be interested in meeting her if I was able to, more so to tell her about what I went through — how the family that came to adopt me treated me and how that was,” Krause said.

Stories of Adoption — Adoptive Parents

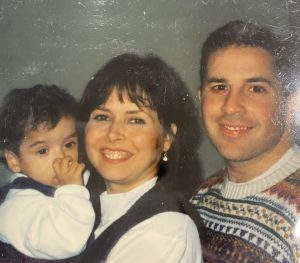

My Family's Story — Karen and Marc Sperber

Don Pollack

At the time when Don Pollak and his wife were beginning the adoption process, if you wanted a domestic infant adoption, you’d have to convince someone to give you their baby.

This was challenging for a number or reasons — they were older parents, which was unappealing to many birth mothers who wanted to adopt. Most were looking for “good christian families,” which they were not.

The very nature of the adoption process in the United States at the time — marketing yourself in the newspapers, putting up fliers — led them to international adoption.

Initially, the Pollaks decided to adopt from China after experiencing some fertility issues. After they had completed most of the adoption process, Elisa, Don’s wife, unexpectedly got pregnant. Unsure how to navigate the pregnancy and the adoption at the same time, they decided to put the adoption on pause.

We called the agency and said, ‘We’ve got something else we’ve got to work on here first, but we’ll be back.” said Don.

When they returned to the agency, they were told that they’d have to start the entire process over again, and because they had a biological child, they would only be able to adopt an older child, likely with special needs and would need to return to China for at least two seperate two-week visits.

“With a newborn in the house, that was a little more than we could take on,” Don said. “So we tabled that discussion and came back a couple years later and went to a different agency.”

They ultimately decided to adopt from Guatemala and adopted their daughter about 23 years ago.

Susie Ritter

Suzie Ritter’s adopted sons never expressed much interest in meeting their birth mother. Though a few opportunities arose, her sons chose to turn them down, feeling better off not knowing. As biological siblings, Ritter often wonders if their familial connection helps offset some of the general trauma of adoption.

Ritter and her husband started looking into adoption after experiencing fertility issues. The biggest challenge was finding a baby to adopt — reluctant to advertise themselves in newspapers and put their names down at agencies, as was common at the time, they decided to enter a private adoption through a friend of her dad’s client whose daughter was having a baby she wanted to put up for adoption.

When it was time to pick up the baby, the adoption fell through; the mother changed her mind.

“When it fell through, we really didn’t know where we were going to turn, where we were going to be able to find an opportunity again,” Ritter said. “It felt like you just had a baby and the baby didn’t survive.”

Luckily for Ritter, her sister secretly made a connection with another mother, this time from Memphis. A little over a month later, she and her husband received a call that there was a baby ready for them to adopt.

Two years later, they got another call — the same two birth parents had another baby and wanted to know if the brothers could be placed together.

While Ritter believes that families can be put together in a million different ways, she still feels that there is a stigma around adoption. And although it never appeared to outwardly affect her kids in their day-to-day life, she suspects it affected them inwardly.

“My kids never chose to share that they were adopted,” Ritter said. “Because my kids share biological parents, they sometimes make jokes about it, but you know they’ll say that there are things that… they don’t know about their bloodline history that is difficult for them, or interest in things that they don’t know what to do with.”

Watch Your Words

Each person interviewed for this project was asked what they wished people understood about adoption and what words and phrases they wished people would be more aware of. Below are their answers.