This year was already a hectic one for USC athletics. Two years ago, the university announced that it would be moving conferences, from the Pac-12 to the Big Ten, starting in the fall of 2024.

That’s a big adjustment on its own, with teams facing new opponents and much longer travel on road trips, to name a couple of ramifications.

Then, last summer, USC President Carol Folt added onto the chaos of 2024. She announced a series of renovations to the university’s athletic spaces: an updated soccer and lacrosse stadium, a remodeled baseball field and state-of-the-art facilities for the football program.

“The three primary objectives of the vision are to position USC Athletics for success with world-class facilities, promote gender equity in support of Title IX and maximize space use through innovative planning,” a statement from the university said.

From the perspective of USC’s athletic department, there’s a clear tradeoff that comes with all of these renovations. In the long run, several programs will receive upgraded facilities that will be especially beneficial against the heightened competition of the Big Ten. But in the short term, some teams won’t play home games on campus for (at least) one season, in the midst of their transition to a new conference. Practice and training schedules will be somewhat messy as well, as teams have to diligently coordinate the use of limited, shared spaces.

Jeff Fucci, USC’s senior associate athletic director of operations and capital initiatives, is one of the administrators overseeing this construction, which began late last fall and is set to continue through 2026.

“Our coaches are completely bought in to where we’re going to go being ultimately worth it,” Fucci said. “We just have to make sure we deliver on that.”

“Everyone will get a lift from this,” Fucci said. “The part that everyone has to contend with is there are short-term challenges. … If we’re going to go through the challenges of the construction, it has to be a really impactful feature, and that’s what we’re committed to doing.”

However, USC’s Division-I teams aren’t the only ones affected by these changes to athletic facilities on campus. Recreational communities will feel the consequences as well.

If you’ve been around USC lately, you’ve probably noticed a lot more construction fences. A new barrier has been added around Howard Jones Field, where the football team practices, covered by signage proclaiming the arrival of “the new home of USC football,” coming in 2026.

Next door on the west side of campus, the stands behind home plate at Dedeaux Field — as well as virtually all neighboring buildings — have vanished. Excavators have been busy for the last several weeks demolishing the 50-year-old home of USC baseball.

Over on West 30th Street, a temporary chain link fence surrounds McAlister Field, though construction notably hasn’t yet begun. Improvements at this facility have been long overdue, given the lack of seating and spectator amenities in the old space. The new Rawlinson Stadium — once completed in early 2025, if contractors can make up for early delays — will feature 1,500 extra seats, a press box, dedicated locker rooms and a natural grass field, among several other upgrades.

In the meantime, USC lacrosse has had to look elsewhere for its home games this spring. They played five games at Dignity Health Sports Park in Carson, about a 20-minute drive from campus. Their last two home contests were at the L.A. Memorial Coliseum.

Players and their families have noticed a significant dip in student attendance this season as a result, but USC Athletics has still created something of a home-field advantage, such as adding plenty of Trojan signage and branding at Dignity Health Sports Park. While gameday traditions aren’t quite the same, players have found new ways to get ready for games, like spending more time with their families and taking advantage of the massive football locker room at the Coliseum.

“I think that got the girls really excited,” USC junior attacker Maddie Dora said after the Trojans’ win over Cal on March 31. “We were dancing the entire time and we had a surround sound system. It was honestly a really fun time.”

After all, it could be worse, as head coach Lindsey Munday noted. As Dedeaux Field is remodeled, USC baseball will have two seasons away from campus, while playing most home games in Irvine — a full hour away.

It’s barely been a decade since the 2012 opening of John McKay Center, USC’s 110,000-square-foot facility for athletics that cost $70 million. In that center are a locker room for the football team, a weight room and a training room, along with dozens of meeting rooms and offices for everyone and everything associated with USC Athletics.

So, why does the Trojan football program already need a new facility?

Of course, with football, it’s no surprise that USC wants to put its most prestigious — and important — athletic program in the best possible position to succeed. Its new three-floor performance center will have everything: player lounges and a locker room, areas dedicated to recruiting and meetings, and several different spaces focused on physical health and development. There will also be a second practice field added parallel to the one that currently stands at Howard Jones Field.

“Anytime you can upgrade your facilities and become one of the top echelon of the college football world from a facilities standpoint, that’s always going to be a great thing,” new defensive line coach Eric Henderson said in February after USC hired him away from the Los Angeles Rams. He also mentioned the upgrades that the Trojans’ coaches will receive with the new building, perhaps alluding to the allure of the facilities in his own decision to jump to the college level this offseason.

Nevertheless, one could argue USC shouldn’t already need major improvements just 12 years later. But, as Fucci explained, a lot has changed in the last decade — and even the last couple of years — in college sports, both at USC and around the country, which makes a new building a necessity.

Various NCAA rule changes, from the transfer portal to NIL to roster and staff sizes, have crowded the building more than originally anticipated. Of course, the athletic department probably didn’t expect to move to the Big Ten when it first planned the McKay Center, and it’s not a coincidence that this project is kicking off as USC prepares for a massive change awaiting in the fall.

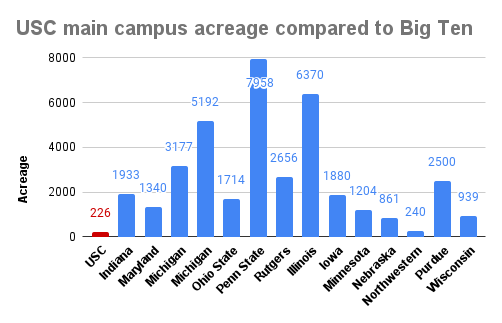

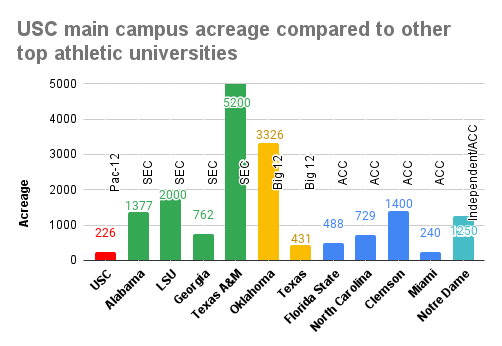

“The peer group has changed,” Fucci said about USC’s player amenities compared to other schools. “We benchmarked ourselves against the Pac-12 and a handful of national competitors. Now, it’s the Big Ten plus national competitors. It’s a step up, so the timing component is good because it creates an urgency.”

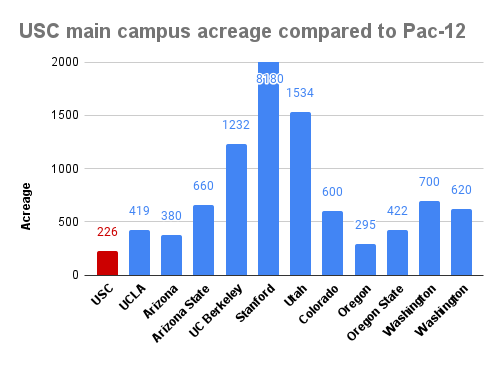

Additionally, Fucci mentioned the limitations of USC’s urban, 226-acre campus, which is dwarfed by other top athletic schools in more sprawled, typical college towns. USC can’t compete with land-grant universities in how much space it can dedicate to sports, which is forcing Fucci and his team to be more purposeful and strategic in developing multi-use facilities that maximize the school’s dense University Park Campus. In fact, out of all universities in the Power Five conferences, USC’s campus is the second-smallest; only the University of Pittsburgh’s 132-acre main campus is smaller.

“How the west side of campus was laid out — from an athletics perspective — wasn’t necessarily the most efficient and responsible use of campus acreage,” Fucci said.

That’s why he and other USC administrators are focused on redesigning these sports-focused areas of campus in a manner that is more sustainable for the future of the university. It’s not simply for the benefit of the football program either, as Fucci asserted that other sports will also reap significant rewards.

The departure of the football program, which currently takes up around half the space in the McKay Center, will open up around 55,000 square feet that will then be allotted to USC’s 20 other teams.

But, shifting pressure off the facilities creates difficulties in other areas of campus — notably at and around Dedeaux Field.

The recreational tennis courts on campus are hidden behind the left field wall of Dedeaux Field, in between Marks Tennis Stadium — where USC’s varsity tennis teams play — and a yard dedicated to the university’s Facilities Planning Management staff.

Dozens of students use that recreation area each day, which consists of five tennis courts and another that has been converted into four pickleball courts. USC offers 16 tennis classes within its physical education department, as well as six pickleball classes that all meet twice a week. The club tennis squad and pickleball club use the courts as their hub; in addition, plenty of students come out to play casually in their free time to get some all-important exercise.

However, in May, the courts will be torn down. In order to make room for that second practice football field, Dedeaux Field will be renovated as well, and moved around 200 feet west towards Vermont Avenue — exactly where the courts currently stand.

As a result, many students are worried about whether or not they’ll be able to play tennis and/or pickleball when they return to campus in the fall. In fact, a petition started by the community has reached over 1,000 signatures, demanding that the school creates a replacement facility by the start of next school year.

Elizabeth Stuart-Chafoo is a USC senior and co-president of the club tennis team on campus. She was one of the organizers of the petition, even though she will no longer be a student once the current courts go away. Still, she emphasized the importance of these recreational athletic communities on campus and hopes that future students will also have the same opportunities that were available to her.

In particular, Stuart-Chafoo was irked by the lack of communication between university administration and the student community regarding the courts. That has led to skepticism on her part as to whether USC will actually create an alternative space for these activities.

Students aren’t the only ones dismayed. Many USC staff would have to deal with the ramifications of not having tennis courts as well.

Michael Munson is an associate director of USC Recreational Sports and a PE pickleball instructor. A lack of courts would affect the university’s ability to offer tennis and pickleball classes, though Munson says that there have been discussions about using Marks Stadium for those courses.

It’s deeper than that, though. Munson emphasized how important it is for him to be able to recreate with students, particularly through pickleball. It’s an easy sport for students and staff to both participate in, and it’s incredibly accessible. With a smaller court, it’s less physically demanding than tennis — people of all ages can easily partake. No expensive equipment is necessary — a set of two paddles and several balls can cost under $20. Not much space is required to play — no need to drive out to a local golf course, for instance. Finally, pickleball has a pretty convenient learning curve — beginners can enjoy it right away.

There is a clear demand for this recreational facility on campus; the courts are typically full during the day, and students often wait 30 minutes to an hour for one to free up. This need particularly exists because of a lack of a clear alternative for students and other members of the surrounding community to play tennis and pickleball. Martin Luther King Jr. Park on Western Avenue has a single tennis court, while Loren Miller Recreation Center has two, but both are a mile away from campus. Otherwise, students need to travel at least three miles to get to a facility with several courts.