May 9, 2025

“Run like a girl.” Once a taunt, is now a statement of power and nowhere was that more evident than at the 40th annual Los Angeles Marathon on March 16. In a rare, electrifying showdown, elite women raced head-to-head against men, showcasing not just endurance and speed, but decades of perseverance that made moments like this possible.

As the cheers faded and the streets of Los Angeles returned to normal, the legacy of this year’s marathon lingers. The race wasn’t just a test of stamina; it was a testament to the women who fought to be seen, heard, and respected in a sport that once shut them out. Today’s elite female marathoners aren’t just racing for medals; they’re carrying forward the grit, rebellion, and triumph of the women who once had to fight simply for a place at the starting line.

For four decades, the LA Marathon has given runners a chance to traverse the City of Angels in one of the country’s most scenic and star-studded races. From the starting line at Dodger Stadium to the pink stars of the Hollywood Walk of Fame, runners get a rare chance to soak in the sights and sounds of Los Angeles on their 26.2-mile journey to the Century City finish line—an experience few get to see in quite this way.

While the masses take on the challenge for personal triumph, there’s another race happening within the race—one unlike anything else in major marathons. Exclusive to Los Angeles, this unique competition adds an extra layer of entertainment and suspense, keeping spectators on edge as they watch this unique competition unfold.

Few sports allow women and men to compete directly against each other. The McCourt Foundation Marathon Chase does just that.

The Marathon Chase is a unique competition embedded in the LA Marathon in which elite female runners receive a head start before the men, creating a dramatic pursuit to the finish. The gap between start times is carefully recalculated each year based on the projected finishing times of that year’s elite runners, ensuring a thrilling and competitive race tailored to the specific field. An additional $10,000 prize is awarded to the first runner to cross the finish line, man or woman.

The format was first introduced in 2004 by Toni Reavis, an award-winning writer and broadcaster specializing in athletics and marathons. Originally known as the “Gender Challenge,” the race added intrigue to the marathon until it was discontinued in 2014 in favor of other elite competitions. But after a pandemic-induced hiatus for many sporting events, The McCourt Foundation’s Chief Operating Officer, Murphy Reinschreiber, saw an opportunity to reignite enthusiasm for the LA Marathon. The Marathon Chase was revived under a new name, once again giving top-tier athletes a platform for an exhilarating battle on the track.

“The Chase was an opportunity for us to revive something that was really sort of a tradition in the fabric of the Los Angeles marathon, at sort of a much cheaper cost than running just an open pro race,” said Reinschreiber. “Once we produced it, everybody remembered how good it was. As a television property, it’s a lot more interesting than a standard marathon in a lot of ways, and so it’s something that we’re committed to now on an annual basis.”

Despite its rich history and high-profile setting, the LA Marathon isn’t considered one of the world’s major marathons. Unlike Boston, London, Berlin, Chicago, New York City, and Tokyo, where world records are often set, the LA Marathon’s course is simply too hilly for that distinction.

The six races that make up the Abbott World Marathon Majors are recognized for their prestige, deep elite fields, and history in the sport. However, for a marathon to be eligible for official world records, it must meet World Athletics’ strict course eligibility requirements, including limitations on net elevation drop. The Boston Marathon, for example, is part of the Majors due to its legacy being the world’s oldest annual marathon, dating back to 1897, but it does not qualify as a record eligible course because of its 137-meter net elevation drop, which exceeds the allowable limit.

The LA Marathon faces a similar restriction when it comes to world records. It’s not a fast course, and it’s not even eligible for world records. While the course is officially certified at 26.2 miles, strict regulations govern what makes a marathon course record-eligible. One key requirement is elevation change: a course cannot have too much downhill per mile, ensuring that records aren’t aided by gravity. The LA Marathon’s rolling terrain and net elevation drop exceed those limits, making it an unqualified venue for setting global bests.

“I mean the drop from Dodger Stadium basically makes it impossible for us to be a legal course,” said Reinschreiber.

Since the LA Marathon isn’t a stage for world records, organizers needed a different way to make it stand out and attract the attention of both elite runners and viewers. That’s where the McCourt Foundation Marathon Chase comes in, a one-of-a-kind competition that adds excitement, strategy and a head-to-head battle between men and women racing directly against each other, something you won’t see at any other major marathon.

In true LA fashion, even the marathon is designed for spectacle.

“We’re not in that Chase, so to speak, for world records, or even really fast running. So, then what’s left, you know, the best thing for us to do is to produce entertaining running,” said Reinschreiber. “And that’s really what the Chase is. It’s really designed for entertainment, it’s good TV.”

Reinschreiber explained that while the goal is always to attract elite athletes and maintain a competitive race, what truly sets the LA Marathon apart is the Chase—designed for pure, edge of your seat entertainment. Broadcast live on KTLA Channel 5, the ultimate shot organizers hope to capture is a dramatic, all-out sprint to the finish, with the fastest man and woman racing toward glory in the final stretch.

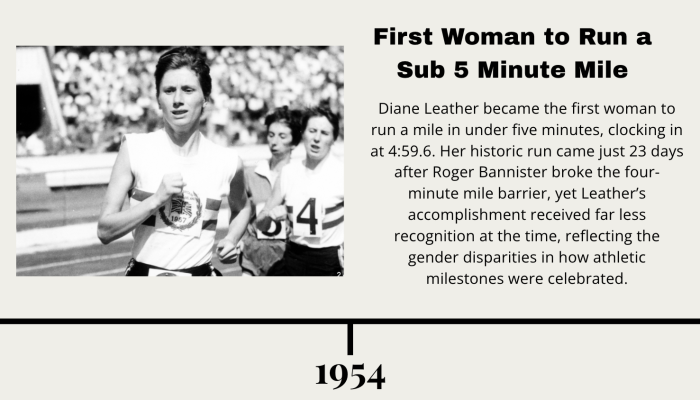

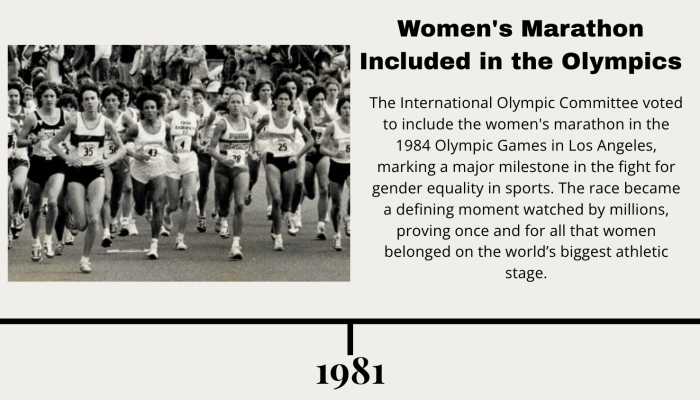

Since its inception, women have dominated the McCourt Foundation Marathon Chase competition, winning 10 of the 14 races held so far. Reflecting the leaps and bounds women have overcome to earn this accreditation in the sport. Although today women’s participation in marathons has become a nearly equal split between men and women, historically that hasn’t always been the case.

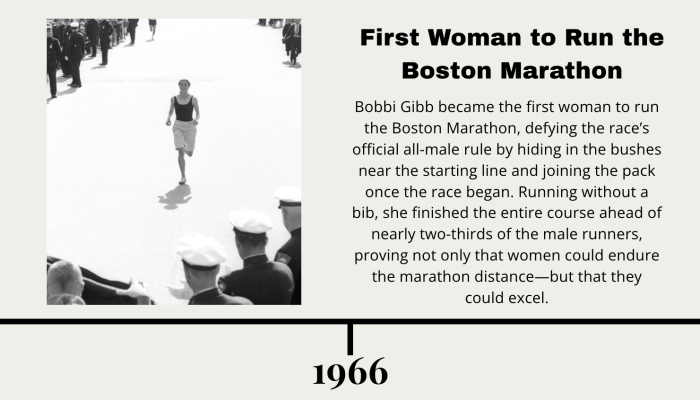

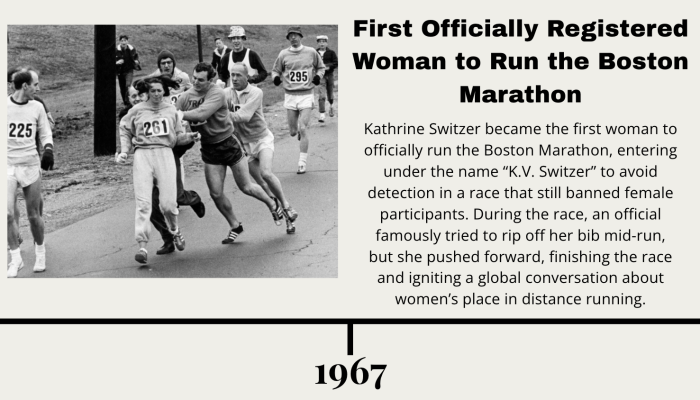

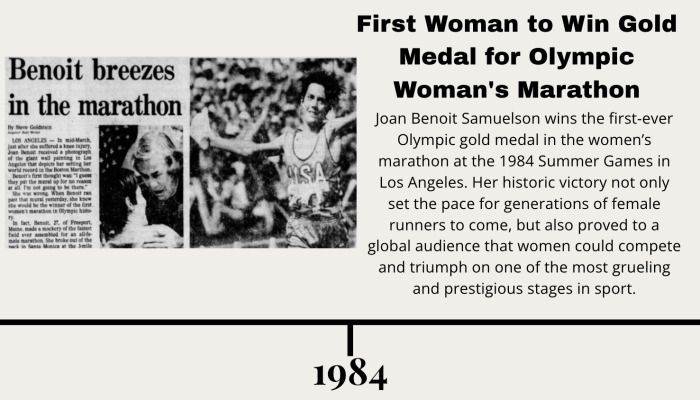

Until 1972, women were officially barred from entering major marathons, including Los Angeles. It was only after years of persistence, protest and quiet defiance by female runners that the Boston Marathon established an official women’s division, allowing other marathons to follow suit, opening the door for future generations.

Maggie Mertens, sports journalist and author of bestselling book Better Faster Farther: How Running Changed Everything We Know About Women said the myths used to justify keeping women out of marathons were deeply rooted and shocking.

“People really believed women would either become infertile, harm their health permanently, or even die if they tried to run 26.2 miles,” Mertens said. “Those fears were wildly unscientific, but they were powerful enough to keep women out for a long time.”

With so much progress, it raises the question: If women have proven they can go the distance, is the head start in the McCourt Foundation Marathon Chase still necessary? Mertens wonders if it’s time we rethink what fairness on the course really looks like.

“When you look at the world records of men versus women in the marathon, I’m pretty sure women come maybe a minute behind the fastest man or like very small margins of a difference,” said Tianna Mcburney-Lin, a five-time marathon runner including two LA Marathons. “If the fastest woman in the world trains a little bit harder, she’ll probably be at the exact same point.”

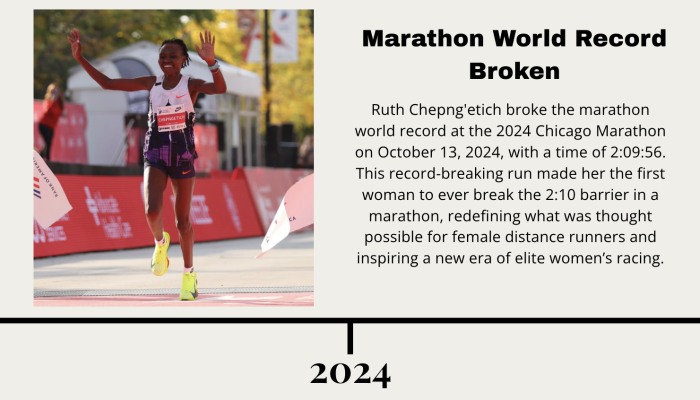

The gap in race times between men and women is shrinking significantly. Currently women run a 25-second slower mile than men and women are only one second behind men in the 100-meter. In the 2023 Boston Marathon the winner of the women’s division, Hellen Obiri, finished before more than a third of the pro male runners. The standing men’s marathon world record set by Kelvin Kiptum is 2:00:35 and the women’s marathon world record set by Ruth Chepng’etich is 2:09:56. So Mcburney-Lin is correct that the margin between men and women’s running does appear smaller than certain stereotypes about the sport might lead you to believe.

But should all this progress omit the inclusion of the head start in the Chase? Reinschreiber doesn’t think so.

“Yeah, it’s necessary, the women’s world record, it was incredible. But that’s still almost 10 minutes behind the men’s world record, you know and maybe 10 years from now we may have a flat start between the two or who knows because the gaps been coming together but it still exists at this point” said Reinschreiber.

Reinschreiber was adamant that taking away the head start would rob the race of its most enticing feature, the final shot of the fastest man and women darting towards the finish line. He also stressed that while the Chase is designed for entertainment, the LA Marathon still upholds the highest standards of elite competition and without the head start, it would lose the very element that sets it apart.

When asked if removing the head start would give the Chase a more competitive edge, Reinschreiber said, “That may be true in the future, but it’s not true right now. And I think if we did that right now, I don’t think the women would be supportive of it because I think they know they would have no chance to win it and that’s not what we’re trying to do here.”

But maybe the question isn’t only about physical ability. Time and time again, women have proven they can shatter barriers once believed immovable—not because their bodies changed, but because the world finally let them in. Still, we continue to let preconceived beliefs shape the rules, often mistaking tradition or assumption for fact. We’ve seen echoes of this before, barriers justified by flawed logic or outdated fears. Perhaps, in some ways, we’re still seeing it now.

But elite women runners don’t let those lingering limitations define them. They tune out the doubt, focus on their own progress, and trust that each personal best chips away at barriers for all women. One of those athletes is Savannah Berry, a pro marathoner who embodies that mindset, running not just for the win, but to prove what women are capable of when given the space to Chase their full potential.

For Berry, running wasn’t just a hobby, it was in her blood. She’s been chasing finish lines since kindergarten, a passion that carried her all the way to a scholarship at Utah Valley University, where she spent four years competing at the collegiate level. But even after graduation, Berry felt she hadn’t hit her stride just yet. In 2019, she laced up for her first marathon and in doing so, opened the door to a professional career that’s still gaining momentum.

Berry has now run over 10 marathons and is an accomplished American long-distance runner whose specialty is marathons and road races. During training seasons, she runs 80 to 85 miles per week which she explained was on the lower end of mileage for elite marathon runners. A choice she makes to prevent injuries but even at that lower standard the miles stack up. By the year’s end Berry’s mileage is in the thousands, a testament to her never-ending endurance and relentless pursuit of progress.

All the never-ending miles and constant physical demand may seem like a runner’s greatest challenge but for Berry, the true test lies somewhere deeper.

“Now it’s more like not doubting yourself sometimes, because there’s so many talented people out there. And again, I wasn’t like the top college runner or anything like that, so keeping the confidence up and just letting yourself, I guess, exceed your expectations,” said Berry. “When my coach gives me a pace that I’m like, hey, that seems like way too fast, or when I’m going into a race against people who literally did run at the Olympics, and give yourself the opportunity to run with those people, kind of not get that imposter syndrome.”

Berry pushes back against self-doubt with the kind of mental resilience that distance running demands, an inner toughness forged over countless miles and moments of uncertainty. Berry explained how she tackles her mental battle during a grueling run by repeating the mantra “It’s just temporary,” in order to finish strong.

When asked about the Chase and the head start that allows women to cross the finish line first, Berry pointed to something beyond physical ability. In her view, it’s a strong mental fortitude, much like her own, that sets women apart.

“I’m not saying women are mentally stronger but they do say running is 2% mental and 98% physical, but that 2% controls the whole 98%,” said Berry. “I think women are just super tough in general and super strong and being able to use that 2% to control the 98%, I think can maybe give us an edge sometimes.”

Marathon runner and member of the Venice Run Club, Kelsey Davenport, agrees that maybe women just have a bigger threshold to push through the mental challenges of running.

“Maybe we just want it more,” said Davenport. “Biologically you know men are probably going to be stronger or faster depending on their bodies, but I feel like women have to give birth, like we have more mental fortitude.”

For decades, myths about women’s fertility and the supposed dangers of long-distance running kept them sidelined from marathons. But today’s runners are living proof of just how wrong those bizarre beliefs were.

“I’ve seen a lot of women who have come back from childbirth and actually started running even better than they were before,” said Berry. “I don’t know if it’s like that mental component, they’re tougher after or if they have a little bit different perspective on how it is, like it’s not so much I have to but I want to and this is something I’m doing for the betterment of me and for my family type of attitude.”

Even though today the thought of a woman running a marathon being the reason to stunt fertility seems outlandish, there was a time when this was widely believed and limitations were put in place to prevent it. While the head start in the LA Marathon Chase may not appear restrictive on the surface, it raises a curious question—could it be quietly setting parameters that prevent women from pushing even further? And in doing so, is it ultimately holding back the competitive potential of the race itself?

Perhaps the head start doesn’t limit women, but levels the field. Given the anatomical differences that can impact performance in endurance events, the Chase might actually offer women the competitive edge needed to keep the race thrilling and fair. Could it be less about holding women back and more about recognizing those differences while still encouraging elite competition?

For Berry the latter is true for this year’s race.

“I mean that gap gets a little bit less every year. But for right now, top men in the country are going to be running quite a bit faster than top women in the country, so I definitely think it’s necessary,” said Berry. “But I will say though there’s been a lot of women who have been doing really well in the past couple years and kind of defied gender norms of women expected to do a little bit less than men. So, I feel like if that keeps continuing, which I can’t imagine it wouldn’t, we’re gonna get closer and closer and that means that the gap maybe won’t be needed.”

But that doesn’t mean more progress can’t be made or shouldn’t be pursued. There was a time when the milestones achieved by today’s female runners were considered out of reach. And while this year’s LA Marathon Chase didn’t mark that shift, who’s to say a future one won’t? Berry said it only takes one woman to prove it’s possible, just like the fearless runners who paved the way before her.

“There was a woman just barely this past year who broke the world record and her time I think opened up a lot of people’s eyes to like wow, how fast can women go. The second the first woman competed in a marathon it opened up a world for women to now compete,” said Berry. “Especially because it is such an individual race it really just takes one person kind of breaking those boundaries for it to be seen that it can be done.”

Progress in women’s distance running has always started with someone daring to go first — to run a little farther, a little faster, and prove what’s possible. Maybe that’s what the Chase is waiting for too. And maybe the next time the LA Marathon Chase plays out, someone else will run fast enough to change what we all thought was possible, again.