Meet the man who ensures USC’s grass is always greener

USC Director of Sports Turf Scott Lupold details his climb to the top of the groundskeeping industry and the crew in charge of USC’s state-of-the-art athletic facilities

By Jack Smith

Scott Lupold’s career started on those steps that day in 2001. The Long Beach native climbed out of the dugout onto the manicured dirt warning track at Dodger Stadium. He stared out at the low-cut grass in the middle of one of baseball’s treasured venues tucked into Chavez Ravine. Understandably, as a lifelong Dodger fan, he was fascinated by the “aura” surrounding the batter’s box. His eyes immediately locked onto the back of Gary Sheffield’s crisp white and blue number 10 jersey, sharing the big-league air with his favorite player who had been picked up in a trade with the Florida Marlins three years prior. Lupold, just 18 years old, was the youngest one on the diamond. He couldn’t stop himself from asking, “What am I doing here?” He was there to work. He was ready to show 56,000 fans and a TV audience what he could do. He was ready to make his MLB debut.

Lupold wasn’t there as a player though.

It was, instead, his first day on the job as a member of the Dodgers’ game day grounds crew. Day One of a career in the groundskeeping industry that would take him to the heights of professional and collegiate sports and into positions to impact the Los Angeles organizations he grew up worshipping. An indispensable industry in the sporting world that still rarely gets the credit or attention it deserves from the fans who flock to watch the events on the fields the workers build, manage and maintain.

Lupold, 42, is now the second longest-tenured Dodgers grounds crew member and also the director of sports turf for USC at the head of a seven-man team in charge of USC’s outdoor athletic facilities including the LA Memorial Coliseum, Dedeaux Field and Howard Jones Field, USC football’s practice space. After breaking in as an 18-year-old, Lupold has become “one of the most known guys” in the groundskeeping industry according to his peer Leo Figueroa, the only member of the Dodgers game day grounds crew that precedes him and has watched him grow from the start.

“Scottie knew from the beginning that he was going to be a groundskeeper,” Figueroa said. “I’m so impressed that, from working a small job as a part-time groundskeeper, he became what he is now.”

Lupold’s start on the Dodger Stadium field, which Figueroa said long-time San Francisco Giants catcher Buster Posey told him is “the best field I’ve ever played on,” is exactly what shaped his lifelong mindset.

“There’s something to be said about standing on the standard and then going to another place and thinking, ‘How do I get this to look like that?’” Lupold said.

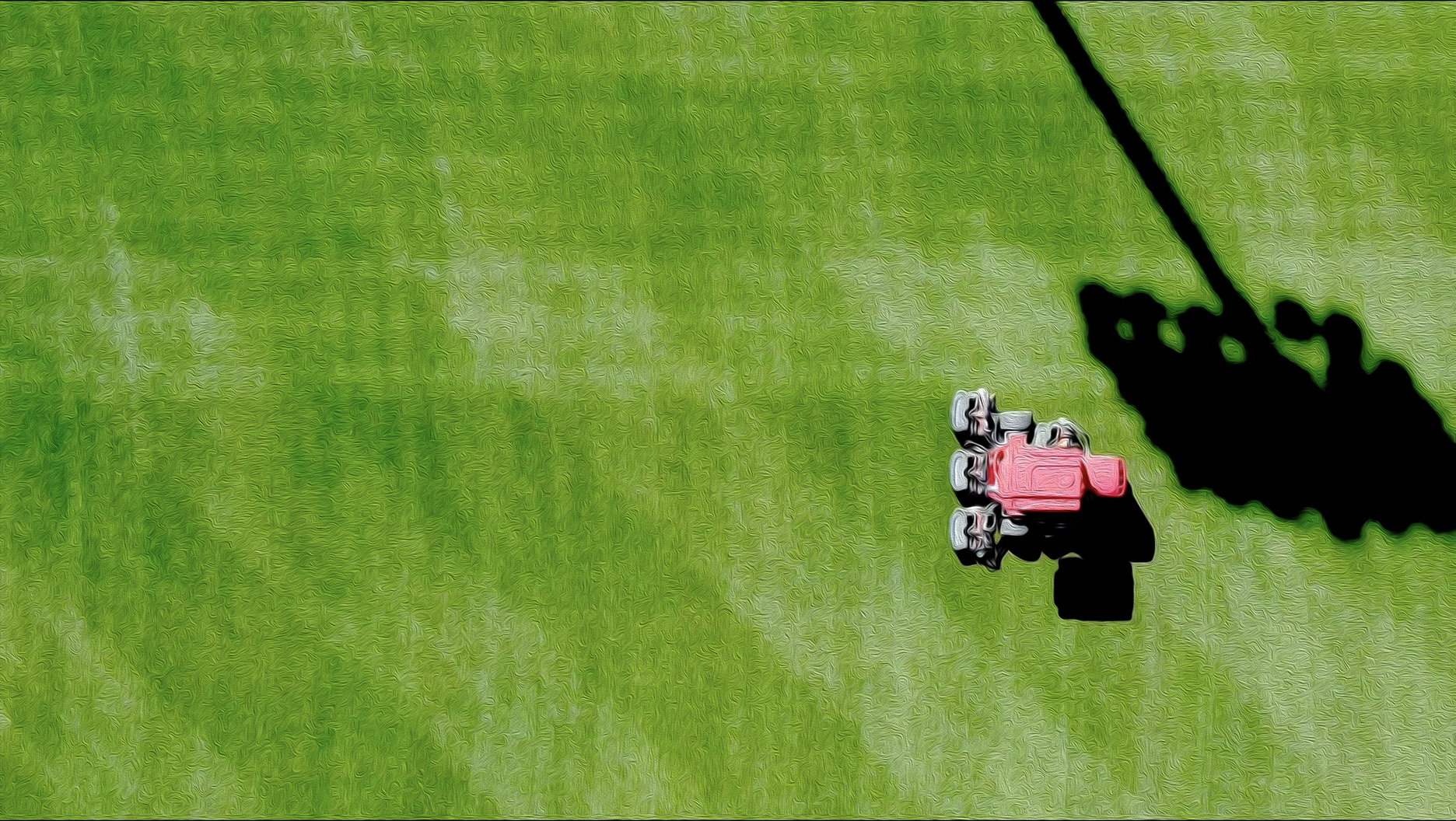

Lupold’s approach sounds simple but it’s not. That becomes clear when you take a ride with him on his weathered, brick-red Toro Workman vehicle, whipping around in what looks like a mix between a golf cart and a lawnmower. As he picked a reporter up at the top of the Coliseum’s tunnel, he reversed course and began to wax poetic about the growth tarps he and his crew laid out that morning over the field. The thin white tarps roll out on top of the grass for about a week, protecting the field from the cold and accelerating the recovery of a surface that hosted six football games the past Fall. He unloaded more knowledge with fleeting mentions of heated soil, light stanchions and how “frost is bad news.”

It’s just a peek into the mind of a man whose bookcase suggests he knows everything there is to know about sod, soil and everything else field-related. As he sat down in his office underneath the Coliseum’s 78,000-seat stadium bowl, Lupold, known by many in the industry as “The Dirt Doctor,” explained how he truly learned it all. He gave some credit to the turf classes he took at what he called a “laundry list” of junior colleges but said he mainly learned from doing.

“You can read all of the books but it’s kind of like life in general,” Lupold said. “You go out there and you start stacking these experiences together, and, before you know it, you’re this finished product down the line that has learned from all of your mistakes.”

Lupold’s early start with the Dodgers gave him the tangible experience that he used as almost a class in itself. He’d just begun driving when he got the gig but he was relied on to maintain a field he’d watched games on growing up with $6 bleacher tickets in his pocket. He would show up to the stadium around an hour and a half before first pitch to help break down the batting cage on the field, put away equipment pregame and drag the infield dirt between innings. He picked it up quickly. So quickly in fact that he “started getting in trouble” overstepping his boundaries at Blair Field at Long Beach State where he also worked.

“I’m a young kid, you know. I’m stepping on people’s toes but I just knew that what I was doing was right,” Lupold said.

Figueroa recalls a specific moment when Lupold, who he called a “goody two shoes,” immediately took over his job painting and chalking the batter’s boxes around home plate before games, a role Figueroa was the “main guy” for during the previous three seasons.

Lupold still does it 24 years later.

Lupold stepped on enough toes to stick on with the Dodgers and land jobs at UC Irvine and the Los Angeles Rams after their return from St. Louis. Because the Rams played their games at the LA Coliseum until SoFi Stadium was completed, a door opened for Lupold to seize his current role at USC.

In 2021, the USC athletic department hired Lupold as its director of sports turf and put him in charge of designing a full field management program from scratch. He was tasked with building a budget, devising a plan for all of USC’s outdoor fields, and hiring six new people to join the crew. It was a big leap for USC toward the cutting edge of the industry.

“It’s almost unheard of, to be quite honest,” Lupold said. “To build an entire crew from scratch and design exactly how you want it done.”

“[USC] was committed to becoming the premier place to play on in the country,” he continued.

Lupold decided he wanted to bring in supervisors for each of USC’s three main facilities: Dedeaux Field, Howard Jones Field and Soni McAlister Field. Under each supervisor, he appointed an assistant.

How did Lupold’s plan work out?

“I don’t think that you can hit more of a home run than we did with this staff,” he said. “When you make six hires, the idea of going six for six is virtually impossible… It was awesome.”

The staff has changed since its inception with members being poached away like assistant coaches in pro sports but Lupold thinks there’s “no chance” that another collegiate grounds crew matches up top to bottom in skill and experience.

That’s a thought shared by the current supervisor of Dedeaux Field, Mike Markulin, who believes it is “hands down” one of the best crews in the country.

Markulin joined Lupold’s staff after serving for seven years as one of the groundskeepers at San Diego State University. At SDSU, he took care of four grass fields and two synthetic turf fields. Now, at USC, Markulin can mainly focus on just one. For him, that’s often an all-day endeavor.

Markulin’s days regularly start at Dedeaux Field at 6:30 a.m. dragging the dirt with a metal carpet-like tool known as a nail drag as his assistant rides a mower across the entirety of the field. He describes the work as being on the dirt and on the grass all day. That includes doing detail work around the mound, the lip of the grass and home plate. He and the rest of the crew will spend the rest of the time leading up to the game watering the warning track, evening out “hot spots” which are underwatered parts of the grass, and painting the field’s lines before first pitch. Once the game ends, it’s back to cleaning up and fixing the spots in dirt and grass affected by the game and preparing for the next day’s game.

By the time he leaves, the clock normally reads somewhere between 11 and 11:30 p.m. When USC is at home, he’ll do it all again the next day.

USC Head Baseball Coach Andy Stankiewicz has heard high praise for Lupold and Markulin’s work firsthand.

“The first year we were on Dedeaux Field I had more [opposing] coaches after the game say, ‘Wow, this field is in unbelievable shape,’ than ever before,” Stankiewicz said.

In the eyes of architecture critic and author of “Ballpark: Baseball in the American City,” Paul Goldberger, “Groundskeeping has an importance in baseball that goes beyond any other sport.”

Goldberger thinks there is “something about the grass and the idea of its near perfection” that makes baseball stadiums feel like cathedrals, giving groundskeepers what he called a “sacred duty.”

“When I go into a ballpark, I always notice the beauty of the grass and always somehow looks greener than I remember,” Goldberger said. “The field has this incredible serenity and calm to it that contrasts with the complexities, chaos and stress of modern life and the built world.”

With Dedeaux Field currently being completely rebuilt and renovated, USC baseball is playing its games across multiple other fields in Southern California, primarily at Great Park Sports Complex in Irvine. Stankiewicz made sure that Lupold was at the front of the planning for the playing surface at the new stadium, which USC plans on completing ahead of the 2026 season.

“I totally trust him one hundred percent,” Stankiewicz said. “He knows what he wants and he knows what we need.”

While they love it, both Lupold and Markulin agree that groundskeeping can be a thankless industry, one that comes with long hours, low pay and, in a world where social media can magnify mistakes, “No news is good news.”

“We’re kind of like umpires,” Lupold pointed out. “Nobody knows who you are and they don’t really notice anything until something is wrong and then once it’s perceived to be wrong, even if it’s not, these things can catch wildfire and before you know it you’re trending on Twitter.”

Lupold agreed that it’s rare they’ll see or hear compliments from fans on how good a field looks but it is incredibly common to see groundskeepers criticized for a field being in bad condition, whether it’s the grounds crew’s fault or some other outside factor like weather, overuse or events like concerts. With that being the case, Lupold’s crew partially analyzes its work through the lens of “What is the guy who sits down at the bar going to think?” If he doesn’t see anything out of place, they’ve done step one of their job.

According to Lupold, there is so much more to a field than its outward appearance though. One of his biggest motivations is crafting a surface that directly influences each sport. He feels a “through the roof” level of responsibility to protect athletes from injury and believes he and his crew can give USC teams a true competitive “home-field advantage.”

Lupold says that every time he sees a player on one of his fields go down hurt, he worries it might be his fault until he sees what happened. In football, if a patch of grass was cut too short or too tall or over/underwatered, there is a chance that the groundskeeper played a part in an injury. In baseball, if a rock was left on the infield dirt or the lip of the grass was edged incorrectly, the same applies.

“You could be on the field 10 hours a day, 360 days a year, but you can never feel every square inch of the field,” Lupold said. “As much as you can think a field is perfect, you just never know.”

With the high-quality work that Lupold’s crew does, however, he feels they can genuinely impact the performance of USC’s biggest sports teams.

Lupold says that because of the historic prevalence of “highly skilled” running backs and wide receivers at USC, they’ve always tried to make the game play “as fast as possible.” Lupold’s calling card is his ability to cut grass as short as humanly possible (known as a “summer grass”) which allows players to sprint and cut faster than on longer, thicker grass. Figueroa says “everyone” in the industry calls him for grass tips if they have problems. So, when Lupold started at USC in 2017, he sat down with then-Trojan Head Coach Clay Helton to discuss the idea of cutting the Coliseum’s grass that low. He remembers Helton’s response:

“Let our guys eat.”

The groundskeeping strategy continues to this day and Lupold’s staff has gotten feedback that it is working from USC’s director of football sports performance Bennie Wylie who told them that players are hitting their personal best speeds on the practice field.

Lupold said the one time he noticed his work have a real impact on a football game came this past Fall when Penn State visited the Coliseum. When Penn State Head Coach James Franklin walked out of the tunnel, Lupold wanted to be out there to see his reaction to a cut that would be foreign to the Midwestern team. Franklin stepped on the field and, according to Lupold, bent over to feel the grass three separate times and began asking people if it was real.

“In the first half of that game, we were taking it to them,” Lupold joked.

When asked if he’d feel like he had an assist if USC won, Lupold said, “Absolutely.”

Lupold wasn’t born with that competitive nature. He was, self-described, the kind of youth baseball player who didn’t want to come up to the plate with the game on the line. He preferred if the guy in front of him made the final out.

He’s different now. Now it’s his driving force.

“This industry is probably the only thing I’ve actually felt like I was probably pretty good at and that I can compete at the highest level at,” Lupold said. “I get so focused on the job that if you notice all the details, you notice it can always be a little bit better.”

“He wants to do the hardest jobs the best,” Figueroa explained.

From Dodger Stadium to the Coliseum, Lupold has taken on the hardest jobs at nearly all of the Los Angeles venues he grew up going to as a fan. He’s built lifelong friendships with other groundskeepers amidst the friendly competitive fire.

“I mean, 15-year-old me would never have believed that this was even possible,” Lupold said.

Flash forward over 25 years and the dream Lupold never could have fathomed has come true. His favorite teams and sports can’t operate without him and his green thumb has graced the eyes of billions of stadium-goers and television viewers. He’s enjoying life at the top of an industry he says he’ll never leave – Great news for all LA sports fans.