The Weight of Survival

They lived through war crimes, and, in their wake, found new purpose.

By: Gordon Redfield-Gale

The Armenian Genocide Martyrs Monument located in Montebello, CA. (Photo By: Gordon Redfield-Gale)

The Day the Soldiers Came

The soldiers came to Emmanuel Habimana’s village, Shyorongi. They were regular people, neighbors even, dressed in makeshift fatigues. Some carried machetes, others guns.

Habimana was 9 years old.

The scariest part about the attackers was the look in their eyes; they were out for blood, he recalled. The mob paraded down the street of Shyorongi, 20 miles north of the Rwandan capital, Kigali. Habimana, a member of the Tutsi ethnic group that has been victimized by the rival Hutus, was no stranger to the threat of death.

“I knew that we were Tutsis by then, because my family had been persecuted so many times,” Habimana said. “Everywhere we lived, everybody hated us.”

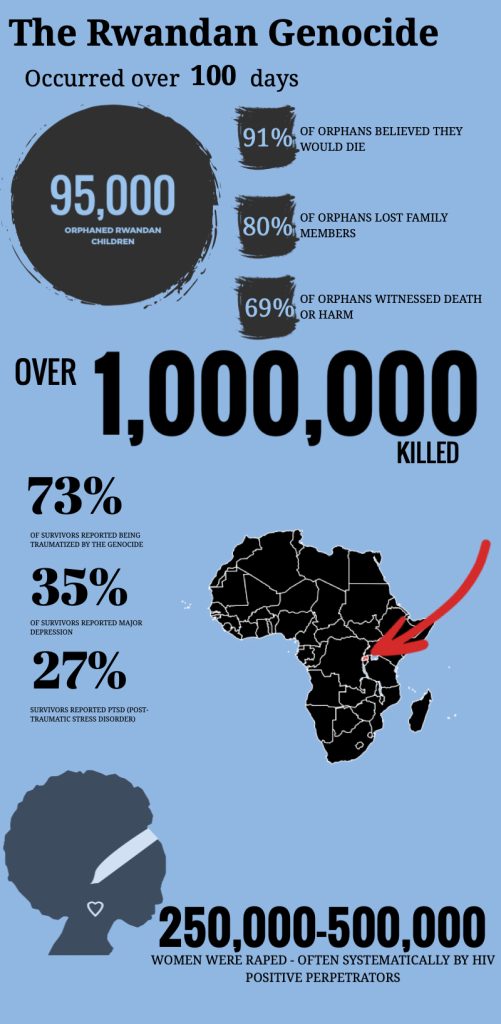

Rwanda has a long, complex history of conflict and persecution, including a civil war that officially concluded in 1993. Despite the end of the war, massacres of Tutsis persisted, and the situation reached a boiling point on April 6, 1994, after a plane carrying the Rwandan and Burundi presidents — both Hutu — was shot down. Hours after the crash, and before an investigation could be conducted, leaders of the Hutu power movement organized the riled up local militia’s and began slaughtering Tutsis.

“We knew that at some point we were going to be killed,” Habimana said.

On April 7, Habimana watched as soldiers entered his house. They hounded his father and, at gunpoint, demanded the young Habimana give up the location of his siblings. He lied, telling the soldiers that they were at the market, which was far from his home. Four of them were hidden at a nearby cathedral. When the fighters’ attention shifted back to his father, the boy ran outside and hid in a bush.

“They shot the husband of my neighbors… and then he died immediately,” Habimana said. “But the woman, she was screaming… as though maybe she was being tortured, or they could have been raping her. Who knows? But she was screaming so hard.”

Then, from his hiding place, Habimana heard a gunshot echo from his family’s house. When the soldiers came out the door shortly after, Habimana realized that the likely target of that gunshot was his father. The boy feared they would search for him next.

When the moment seemed right, he ran — leaving his village, and his childhood, behind. He left the remains of his father and whomever might have survived of his mother and eight siblings. He ran for his life. Not only was he running from the soldiers, he was running from the bullet that killed his father.

“I thought maybe after killing my dad, maybe the bullet wants to find everybody,” he said. “So when I was running, I was running as fast as I can. I hide as much as I can.”

Habimana described how when traveling, he would stand in the middle of groups, so the bullet which killed his father would not be able to find him. To Habimana, it was a hornet, a heat-seeking missile, which would not stop until he was dead.

Thirty years later, in some ways, Habimana is still running. He lives in Texas, working as a manufacturing technician for a company called Applied Materials.

But Habimana does not hide from the horror he experienced as a child. Instead he runs from the threat of failure and letting down those who lost their lives.

For people who survive these sorts of traumatic moments — whether in Rwanda, Armenia, the Khmer Rouge’s Cambodia in the 1970s, or Nazi Germany — the struggle to find a sense of place and purpose can last decades, or a lifetime.

“When one has been through this type of trauma, it can feel like, well, what’s the purpose of life? What are we supposed to do with ourselves?” Dr. Valentina Ogaryan, an Armenian clinical psychologist, asked. “I think helping find meaning again, can give the will to live.”

Some, like Habimana find grounding in communities where people have survived similar traumas, either seeking unity through sharing their experiences or discovering solidarity in silence. Others, like Naireh Poghosyan-Melkonyan find purpose by helping others.

“Individuals do tend to become resilient after these traumatic incidences…it comes back to social connectedness, really being able to feel that you’re connected to others, to your community, to your sense of self,” said Dr. Ogaryan.

‘Art is the Best Doctor’

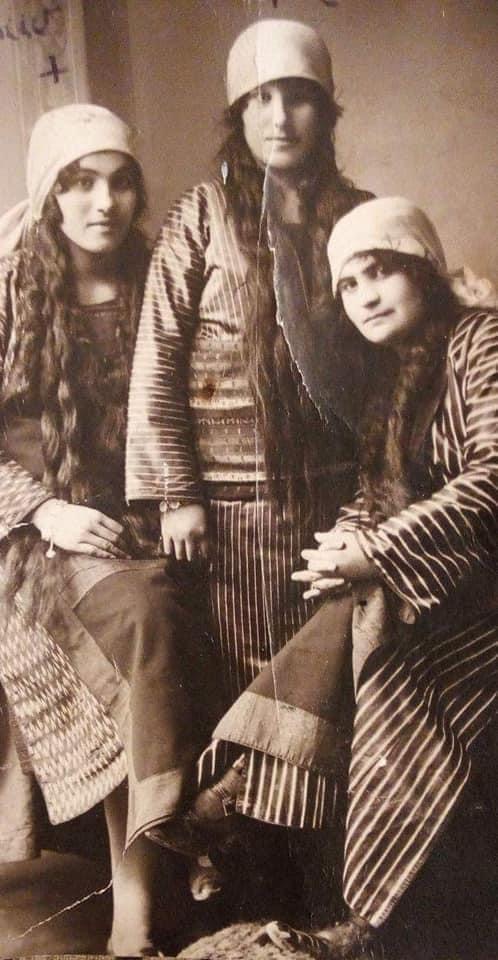

Naireh Poghosyan-Melkonyan is a descendant of Armenian genocide survivors. The contents of her grandfather’s journal are a firm reminder of the terror experienced by family members just two generations ago, when the Ottoman Empire systematically murdered over a million Armenians. But this dark history did not influence the family’s demeanor.

Poghosyan Melkonyan said memories of her family and childhood always make her smile

“Whenever I read the memories of my grandfather, what did they do during the genocide with his sisters — they rape and kill them. They burned my grandfather’s mother. They hang my grandfather’s four brothers.” the 51-year-old Poghosyan-Melkonyan said. “My father lost all his family, his aunts, his uncles, but [my parents] never, never injected hatred to us.”

More than a century after the end of the genocide, Armenia still faces challenges.

In 2016, a conflict between Armenia and the neighboring nation of Azerbaijan over the territory known as Artsakh reemerged, escalating into warfare, as it did soon after the Soviet Union collapsed in the late 1980s. Poghosyan-Melkonyan was concerned history might repeat itself.

“[The Azerbaijani] spread some videos where they show how they were treating people, peaceful people. They were caught beheading the people. They were killing them. Of course, as a woman, I have scaries,” she said. “They were ruining our culture, our history.”

Her husband, Armen Gevorgyan, was a colonel in the Armenian army who was sometimes sent out for peacekeeping operations. Poghosyan-Melkonyan said his unrelenting optimism alleviated some of her fear.

When the conflict boiled over again in more sustained fighting in 2020, Armen couldn’t bear to watch as “20 year-old children” fought on the front lines while he sat at home, Poghosyan-Melkonyan said.

He resigned from his position as Colonel and volunteered to fight alongside the younger soldiers protecting the Artsakh borders. As always, he promised Poghosyan-Melkonyan that everything would be okay.

On the 30th day of conflict, Poghosyan-Melkonyan was informed her husband was killed by a drone.

“The first period I thought that everything is destroyed. I cannot survive. I cannot live after his death,” she said. He was, she added, “the strongest person in the world.”

She felt isolated, as though she was the only one who had lost a husband, as though her son was the only one to lose a father.

So, she sought out other families that had lost relatives, including one that lost a father and twin sons. She saw how this family, who lost everything, was moving forward with their lives, and realized she must discover a way to do the same.

Her son, Avet, who was five-years-old at the time, was devastated by his father’s death. The boy tried to hide his sadness, expressing unrelenting faith in his father’s eventual return — even after the child could comprehend the loss.

“He goes to the corners [to] hug the photo of his father,” she said. Sometimes he speaks,” Poghosyan-Melkonyan said.

“He didn’t want to laugh. He didn’t want to smile. He didn’t want to sing,” she added, “it was very sad to see that this joyful boy became very sad.”

Determined to help her son rediscover his joyfulness, she brought Avet to visit a musical school. When he was asked to play a musical instrument, she saw some of his characteristic happiness return.

This sparked an idea. Poghosyan-Melkonyan had connected with many families with children who seemed similarly lost and purposeless. If music could help her child heal, perhaps it would have the same effect on other children.

Poghosyan-Melkonyan decided to open an art school. No, she was not a teacher or an artist, but children were grieving, and most mothers did not have time to take them to school. She was determined to help children like her son heal.

On the first day the school, Home of the Sons, opened, there were 22 children. Unsure what the curriculum of the school should be, Poghoysan-Melkonyan and the children spent the first day simply expressing their grief.

“We spoke a lot. We had a lot of tears. It was very sorrowful to see how a 5-year-old boy or girl miss their fathers, their brothers. It was very harmful. But I told [them] that you see this pain everyday in your families, please when you come to school, leave everything at home and come to have joy, happiness.”

By working with students and scouring Youtube for art projects, Poghosyan-Melkonyan’s school transformed into a center for healing through the arts. Now, the school has 46 in-person students, and an additional 92 take part online.

Not only did the school help Avet and dozens of other children rediscover joy, Poghosyan-Melkonyan found helping these children contributed to her personal healing process.

“Whenever I see them, my heart start to beat very loudly and very quickly. I love them all and of course whenever we have contests and they have victories. It is great joy, great joy,” she said. “My school helped me a lot and it healed my pains.”

For Poghosyan-Melkonyan, she stumbled across her calling.

At a moment when she felt most alone, she connected with other survivors in mourning. Then her artistically inclined child led her to the creative workplace. There she discovered her purpose.

“When we talk to each other during creating something, of course it is better,” she said. “When you help somebody, you feel satisfied. You understand that you could do something very little, very little, that makes the person feel happy. You will make him smile, and it is very important for our life.”

Dr. Ogaryan, who contributes to The Promise Armenian Institute at UCLA, views survivors of the 1915 genocide and their descendants as a protypical example of the struggle to move forward.

“If I think about the Armenians who attempted to march to the desert during the genocide, I mean, it’s horrifying to kind of imagine witnessing that type of violence. And then you’re left pondering, ‘Well, how do you come back from that?’”

Many who seek to answer this question, Dr. Ogaryan included, draw upon the work of Viktor Frankl. A renowned neurologist and psychologist who studied the concept of meaning from his perspective as a Holocaust survivor. He believed that meaning was derived from the struggle to achieve an overarching goal.

Dr. Ogaryan believes offering your service to a community could represent that goal.

“Essentially, finding something that you’re passionate about, that you can give back to or contribute to, and then looking through your values through various mediums, whether it’s beauty through art, lust through a relationship, etc.”

In the case of Poghosyan-Melkonyan, she discovered purpose by helping these children recover.

For her, art can be a tool for connection and rehabilitation.

“Art is the best doctor,” she said. “Your mind starts to work and you find different ways to calm your pain.”

The Duty of an Exile

For all intents and purposes, Emmanuel Habimana is an exile; Even 30 years later, he is convinced it is unsafe for him to return to Rwanda. Now, he tries to move forward.

“I leave my past behind,” he said. Although Habimana will never forget what happened, he hopes his experiences will not torment him, adding “let me be in peace with it.”

Habimana was once dedicated to sharing his experience with others. He traveled to schools across the US, trying to tell people what he and his country had lived through, two decades removed from the tragedy itself.

Working with a young filmmaker, Natalia Ledford, he co-directed a National Geographic-funded documentary about the genocide and his experience in particular.

He had hoped that by sharing his story it might provide hope to other orphans. But Habimana was not searching for sympathy, and was disheartened by the reaction of those who could not relate to his trauma.

He was confronted by people who believed his story was part of an elaborate hoax, Habimana said. They believed the genocide is “a lie that we created just to get the world’s attention.”

Habimana’s experience demonstrated the struggle survivors have when attempting to generate empathetic connections with people who have not lived through a genocide.

He thinks people unfamiliar with intense stories of survival try to rationalize their inability to comprehend the experience by either pitying the individual or doubting the veracity of the account.

“I don’t like when I’m being portrayed as a victim, as somebody who needs pity,” Habimana said. “The majority of people don’t know how to sympathize without making you a victim. There is more in me than just, being a survivor, being a victim.”

Eventually, Habimana stopped touring schools. He said he was having a mental breakdown, which even today he is still recovering from. He discovered that the more he talked about his experiences, the more they weighed on him.

Dr. Beth Meyerowitz, a clinical psychologist who studied the Rwandan genocide and the children it orphaned, said it is important for survivors to share their experience — when they feel comfortable. Because people talk about the weight of survival so rarely, the experience can become very isolating. Sharing can release an individual from their solitary state.

“They don’t want to feel pity, and I think they also don’t want ‘Oh, my God, you were so brave,’” she explained, “nobody wants that, right? You want a human interaction where somebody really listens to you, hears what you’re saying, lets you talk, doesn’t constantly interrupt, lets you say what you have to say and really listens and is there for that, for hearing that with the empathy that’s involved, but without making them into an object of your pity.”

Habimana was even more discouraged when he returned to Shyorongi to work on a second documentary. He said with the cameras around, he was safe, but people killed his family’s cows. He received a phone call threatening the same fate if he ever returned to Rwanda.

The original documentary co-created by Habimana was called Komora: To Heal. He created the documentary with the intention of helping orphans struggling to find their place, but hoped the process might also facilitate his own healing.

A critical component of this healing process is the concept of forgiveness. Because of these harmful experiences — death threats in Rwanda, and deniers in America — Habimana started to question his ability to forgive.

“I see, like there’s still an idea– anti-Tutsi, anti-survivors,” he said. “Maybe I need to stop… this public speaking about forgiveness because I don’t believe it anymore.”

Although Habimana said he is willing to forgive people, he is still unable to forgive those who actually perpetrated the crimes. Two members of the Interahamwe (the civilian paramilitary group that carried out killings) live in his village and many others. He shook their hands, but when they asked for forgiveness, he could not offer it.

“I think there’s a lot of potential healing that happens when you’re able to forgive some person or entity that… caused or inflicted pain, but we have to be really careful,” Dr. Ogaryan said. “I don’t know that anyone would relate to saying ‘I forgive my perpetrators.’”

From her experience interviewing survivors in Rwanda, Meyerowitz believes there are other ways for people to heal. Forgiveness is not always an essential element to a survivor’s rehabilitation process.

Habimana thinks connecting with other survivors is crucial.

“Everyone has their own way to deal with what is going on inside their heads. But if you want to socialize, I think it’s very, very important you socialize with the people who understand what you are going through, who can relate, who can sympathize otherwise. Other people see us as crazy people,” he said. “Really, really… few people really understand what we went through.”

Because of his experience traveling around schools, Habimana understands the importance of sharing with those who come from a similar background. Survivor communities provide opportunities to share experiences in sheltered environments.

Meyerowitz spent time with one such community in Rwanda, called Solace Ministries, that attempts to respond to various needs of survivors. A community like this does not require people to share. Instead, it meets the survivors with support, love, and generosity, she said.

“You’ve been chosen because of the community you’re in. Because you’re Tutsi, because you’re Jewish, because you’re Armenian,” Meyerowitz said. Restoring that sense of community can provide survivors with “somebody who might understand what you’ve gone through and loves you anyway, who isn’t shamed by what you’ve been through.”

Connecting with other survivors in Rwanda provided Habimana with a different type of support: a sense of perspective.

“You talk to other orphans and you see, they’re even living in a worse lifestyle than mine. And then you learn from them,” he said. “I can go to school, I can still walk. But these people, they don’t have nothing.”

Coming face to face with the reality of other’s experiences can work wonders for a survivor, just as it does for us.

Whether a survivor meeting other survivors, or a “normal person” hearing a survivor’s story for the first time, we are confronted with the truth. We are not alone in our struggle, and in fact, others may be struggling much more.

Habimana believes there are three categories of people: those who are hopeful, those who don’t care, and people who “completely lost their hopes about life and [are] waiting to die.”

Habimana said he sometimes feels like a member of the third group.

“I feel like I want to give up. I guess sometimes I wish I could have been gone. But on the other side, I feel like maybe, maybe somewhere, there is a reason why I’m here. There is a reason why I’m still living,” he said. “Maybe there is a mission that I have to complete… on behalf of those that we lost.”

A Genuine Connection

Amidst the murky path of survival emerges a central question: How do individuals carrying the burden of survival find the strength to carry on their lives?

Ogaryan and Meyerowitz concur that each survivor’s journey is as unique as a fingerprint. There is no prescribed path to healing; each must chart their course, navigating the grief, and developing resilience.

“There are different ways people react,” Meyerowitz explained, “based on the specific experiences they had, what their own past lives brought to it, what sort of resources and social support they have now, to be able to grapple with what they’ve gone through.”

Amidst the clamor of diverging narratives, there lies a fundamental truth: the importance of genuine empathy and understanding. Emmanuel Habimana, weary from the ceaseless battle for recognition and validation, implored, “My only hope is to have people sympathize, understand — but I am tired, so now I don’t even want to talk about it.”

After three decades, the burden of the past is too much. It is also isolating, leading to a quest for connection and understanding.

“Can one find people or connection where they can feel heard, and they can feel understood, and they can be willing to talk about their experience with the understanding that you know, who they’re going to talk about may really not understand,” Dr Ogaryan elucidated. “But if they’re willing to listen, if they’re willing to witness, as they’re talking about their experience, that can be very powerful and transformative, too.”

Genuine conversations can help a survivor discover a sense of purpose, as Habimana and Poghosyan-Melkonyan’s experiences demonstrate. Both have a strong desire to lead lives in place of those who were not fortunate to survive.

Although Habimana still searches for an objective, Poghosyan-Melkonyan found her calling, surrounded by the supportive network of her school.

“When we have sorrows, we have pains, we want to recover from it together. We are happy together, we are sad together, we are disappointed together. Everything we do together.”