Nuestra Identidad/Our Identity

My multi-generation quest to understand the relationship between Spanish and being Latino.

There’s an African proverb that reads, “the child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth.” I remember learning about it when I was younger and it has stuck with me for years. While being from a different tradition, I still feel a personal connection to it.

When reading the proverb, I think of identity (or lack thereof) and wanting to belong. That unrelenting desire to want to be included by any means necessary. It’s part of what makes us human, and it’s a train of thought I circle back to constantly, especially as I have gotten older.

Part of this is attributed to my mutli-ethnic background and trying to figure out where I belong in regards to my communities. Frustration, confusion and sadness are some of the emotions caused by this internal back and forth.

Up to this point, these emotions were kept internal — I rarely, if ever, discussed this with others, even the strongest people in my support circle. Now I want to change that.

I knew others around me shared similar experiences of belonging, especially in the Latino community. Arguably the biggest catalyst for this is the Spanish language. My lack of fluency in the language garnered mixed feelings of inclusion from those around me.

I wanted to understand why. Why does language carry so much weight about what it means to be Latino? Why does this “line in the sand” exist in the first place? All of this questioning led me to realize there is so much tension within my community, and one family’s story captures this tension.

My family’s story.

So I went about the journey as a journalist, not as a family member, to understand more about language and, more importantly, my village.

Respecting Elders

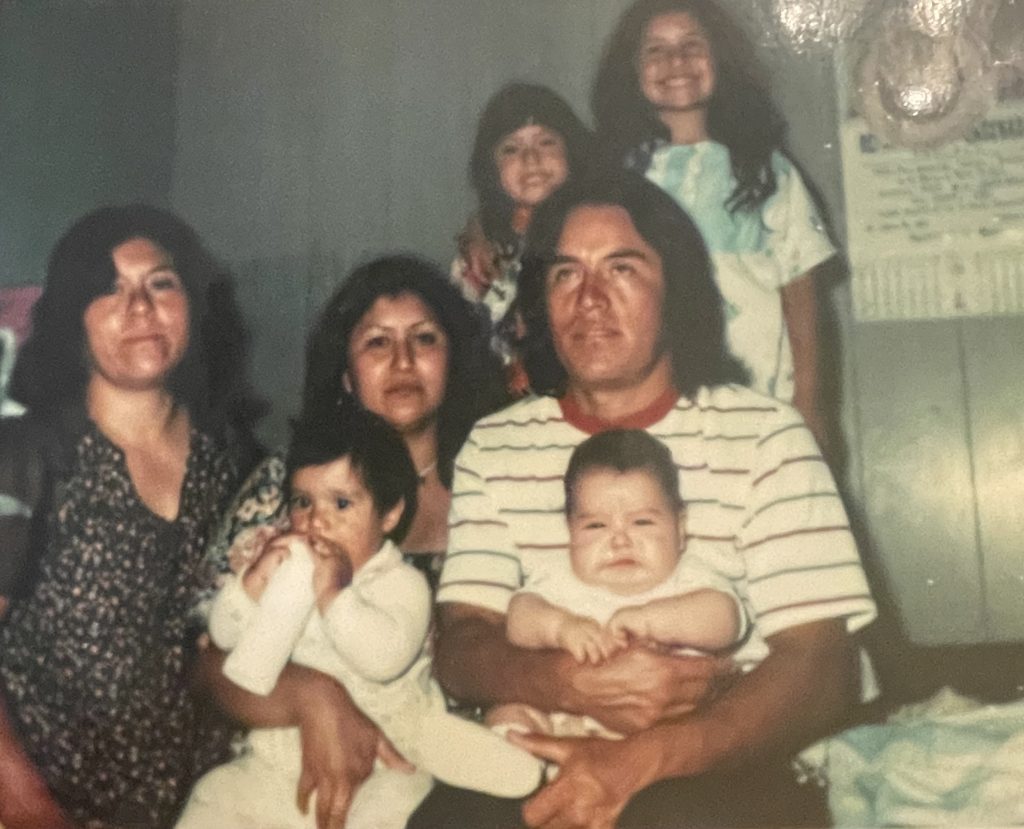

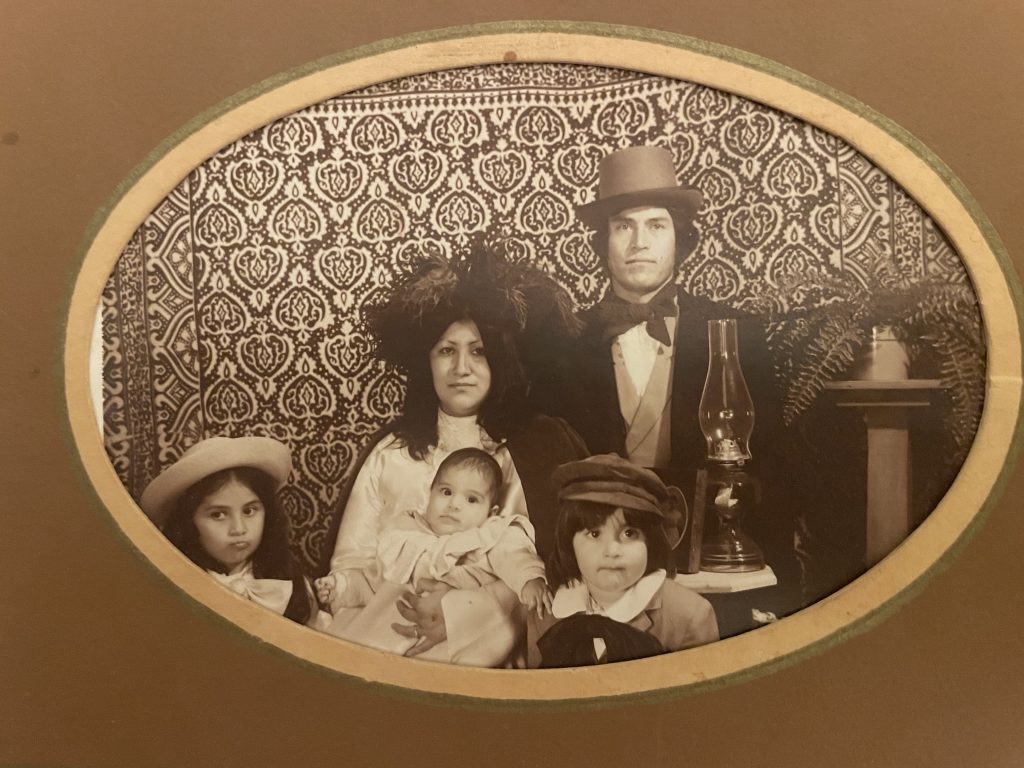

and other family relatives (courtesy of the Villalpando family).

Manuel Villalpando never imagined this could happen in his life. After decades of living in the same house with his wife, Martha, raising three children, and seeing them raise families of their own, he thought his days of being a paternal figure were over.

That was until James the cat arrived. A Christmas gift for one of his grandchildren, the tabby cat with a short ear was the latest child to run around in their home.

Embodying the classic trope of a parent not wanting an animal then treating it better than their own children, James became a beloved family member quickly. The two had their own morning routine and even their own “conversations” together in both English and Spanish. With Spanish being his first language, Villalpando frequently spoke to his “gatito” in Spanish and if you paid attention long enough, you would think James fully understood it.

After over a decade together, the jury’s still out on James’ comprehension, but speaking Spanish to his household sidekick is more than a comfort thing for Villalpando. It is just one of the ways he continues to practice his native language.

“I didn’t learn English until I came to this country … when I was about 18 years old,” Villalpando said. “I came to this country and I went to night school to learn English, then also work.”

Like many of those who have immigrated to the United States, Villalpando came to this country looking for greater opportunities to provide for both himself and his family back home. Originally from Zacatecas, he did everything from working in the fields picking sweet peas to construction. All while working to learn a new language.

“I could not speak Spanish in any environment I was in because everybody spoke English,” he said. “The only time I spoke Spanish, [was] if they asked me, ‘How do you say something in Spanish?’”

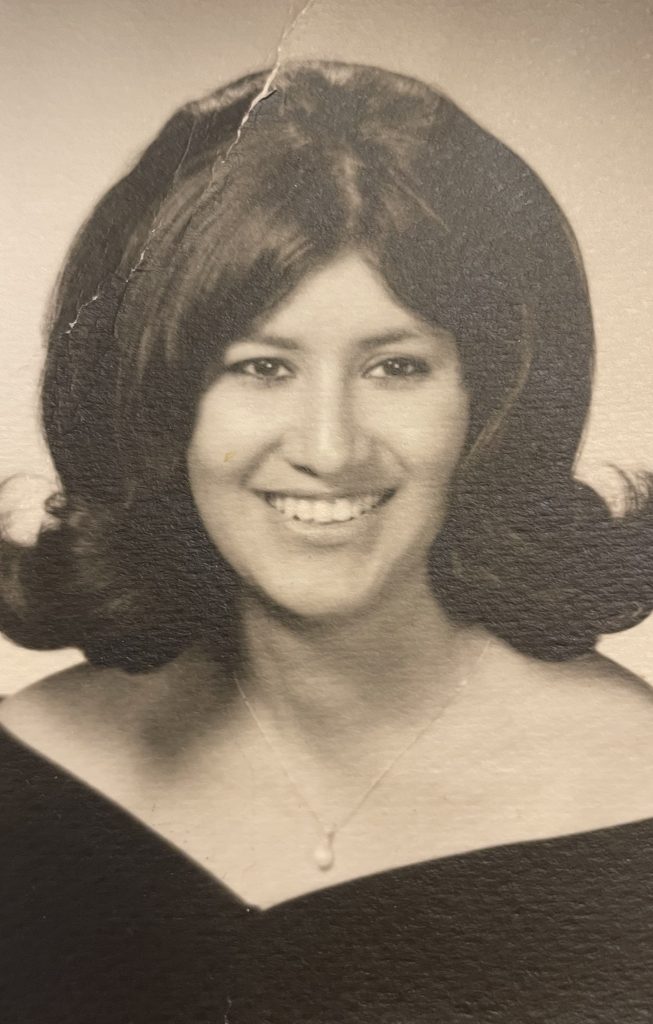

Martha Villalpando

“La Matriarca”

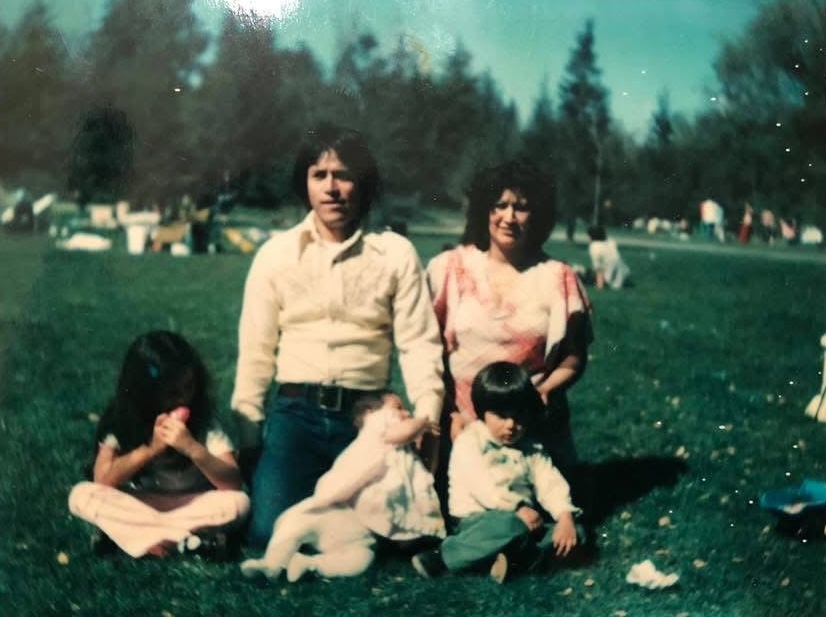

Los Villalpandos

Circa 1977

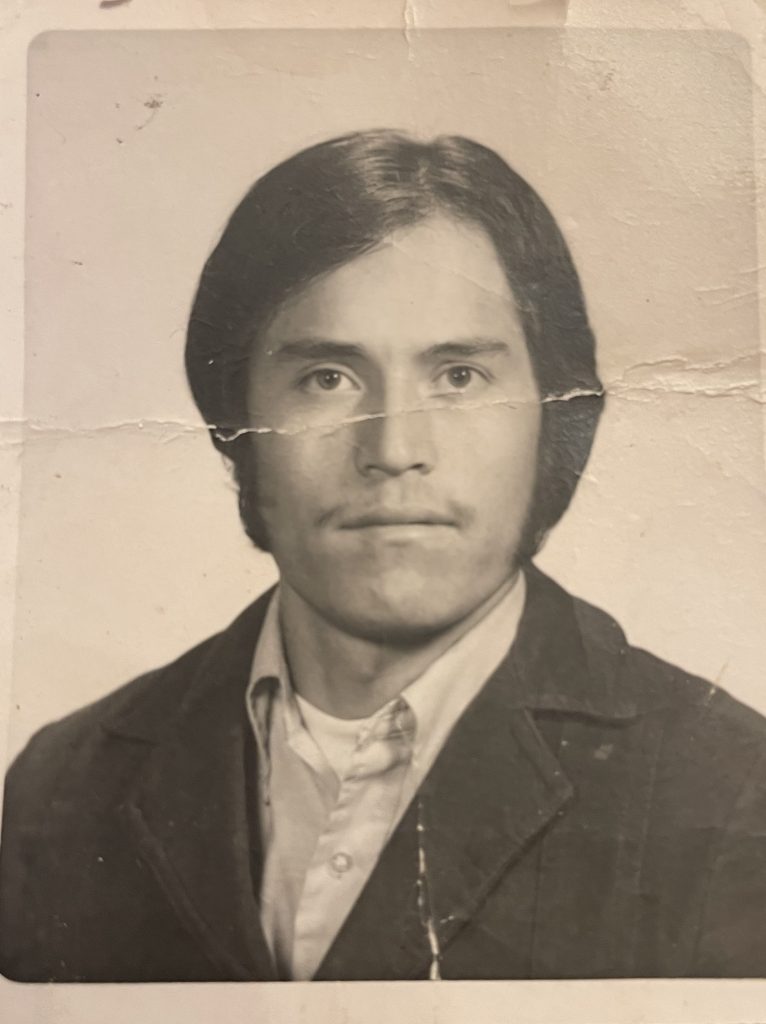

Manuel Villalpando

“El Patriarca”

This pressure to assimilate via language is not a unique experience as Amelia Tseng, a linguistics and Spanish professor at American University, explains how outside factors force this change.

“There’s still a lot of racism in the United States, people are getting yelled at on the streets for speaking Spanish, schools really don’t have the support there most of the time to help people maintain their home languages,” Tseng said. “It creates a situation where…there’s a lot of silent and institutional and societal pressure to shift to English.”

Both Manuel and Martha Villalpando learned English out of necessity to conform to societal standards, albeit through different scenarios. Martha grew up first generation on California’s Central Coast and her journey to bilingualism was a product of her upbringing.

“When I started school, I didn’t know how to speak English. All I spoke was Spanish, so it was kind of hard, but when you’re little and you’re at school, you pick it up faster,” she said. “And when I came home, my parents didn’t speak a lot of English so we spoke Spanish.”

Needing to speak two different languages to get around seems like a daunting task, especially as a child. However, not knowing anything else desensitized Martha to believe her situation was normal.

“San Luis Obispo didn’t have very many Latinos,” she said, remembering her time growing up in the 1950s. “[A]nd there was nothing in Spanish like there is now so to me it was normal because my aunt didn’t speak English and my cousin spoke Spanish and English.”

Assimilating into the U.S. comes in many forms for immigrants, often resulting in a reduced or lack of speaking in one’s native language. However, the Villalpandos continued to practice Spanish around those who understood and when the time came to teach their first child, Sandra, they did it to literally keep her connected with their village.

“We taught her how to speak Spanish because we used to go to Mexico,” Martha said. “She could learn to speak with her grandpa, her parents, her grandparents in Mexico, and then she could speak with my parents.”

But that did not carry over into their other two children. Once again, a lack of teaching was a product of circumstance.

“At the beginning of my construction life, I was trying to learn how to get along with everybody by learning English, so I also practiced with [the kids] at home,” Manuel said. “I wish I would’ve spoken Spanish to them only but I didn’t.”

Martha viewed this decision in a similar way as a “greater good” for the ability of their family to better assimilate and progress forward.

“It was just easier for me, it was easier just to speak English to [our kids],” Martha said. “I felt that if I spoke English at the house and even to the kids, [Manuel] would speak more English instead of just all Spanish.”

Even at the time, the parents understood the potential issues of their children not speaking Spanish fluently, but the ability to be better prepared for the world around them — a world the home’s patriarch was actively adjusting to — was more important. Yet, when looking back on his children’s upbringing, Manuel wishes he would have done something different.

“I wish that I would have spoken nothing but Spanish to them, because I was still learning English at work anyway and going to night school,” he said. “I consider that a mistake.”

However, this “mistake” to not have Spanish-fluent kids did not change how the parents perceive their kids in terms of being “authentically” Latino, or any other Latinos for that matter. That “authenticity” comes from so much more. According to the Villalpandos, being a Latino includes your ancestry but also how much you immerse yourself in the culture through food, music, and traditions.

“I wish I would have spoken nothing but Spanish to them…I consider that a mistake.” – Manuel Villalpando

Praises of the Father

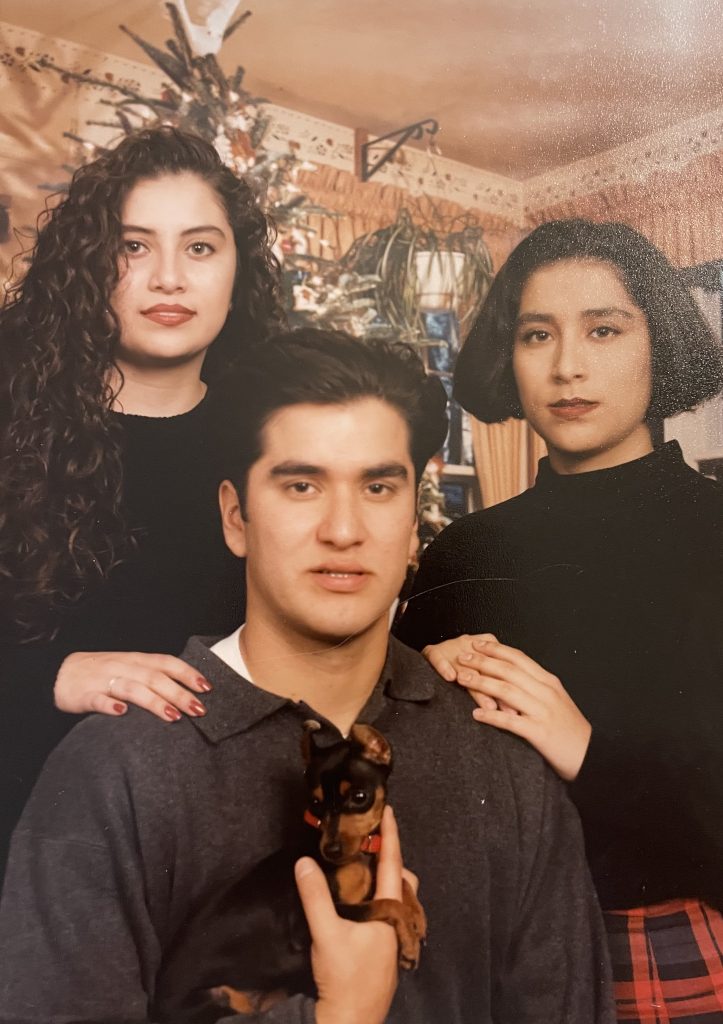

Sandra, Shante, and Manny (courtesy of the Villalpando family).

While it felt refreshing to hear about the older generation’s lack of judgment toward Latinos not fluent in Spanish, that doesn’t necessarily mean the next generation received the same treatment for their lack of knowledge.

“Growing up, I always felt a little out of sorts, because I never spoke it fluently,” said Shante Galbraith, the Villalpandos’ youngest child, now 48. “I understood it perfectly, so I always understood what they were saying … but I always felt a little out of sorts and awkward because I didn’t speak it fluently, so I was never confident enough to respond to them.”

Despite feeling out of place at times, Galbraith explained that she didn’t feel different from her fluent family. While communication issues existed, it wasn’t until she got older that she noticed a lack of Spanish actually being a barrier.

“Growing up, I never felt like I couldn’t communicate with [my family] … That’s why for the longest time I felt like not knowing Spanish wasn’t a barrier,” Galbraith said. “It wasn’t until I was more aware as a teenager that I became more aware and realized, ‘Oh maybe this is a barrier.’”

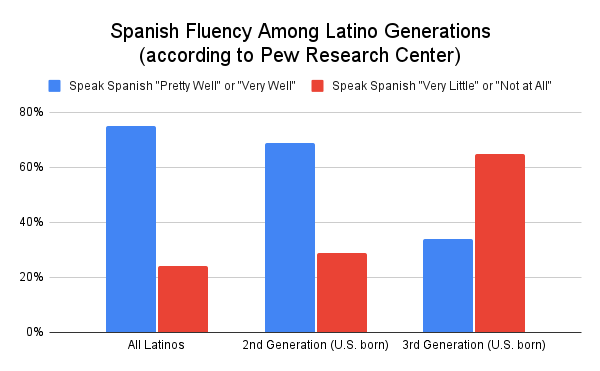

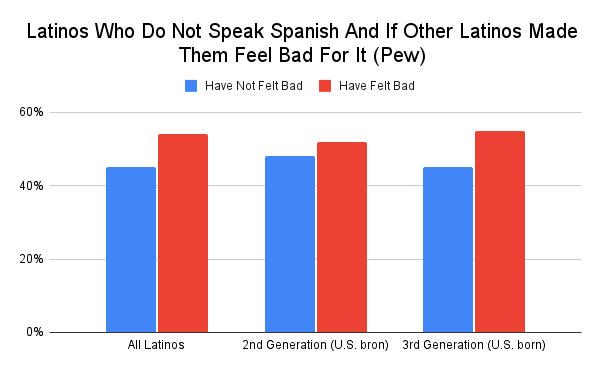

This “barrier” is not exclusive to only some Latinos, as a 2023 Pew Research Center study shows that only 57% of U.S.-born Latinos say they can carry a conversation “pretty well” or “very well” in Spanish. Many of those who can’t are what Tseng calls “heritage speakers,” or those who have a heritage relationship with the language but aren’t “perfect bilinguals.”

and Shante Villalpando

(courtesy of the Villalpando family).

Data shows that a rift has developed within the Latino community, but this is nothing new. Outside of her family, Galbraith noticed the divide between kids she grew up with based primarily on whether they knew Spanish.

“Where I grew up, there was two Latin-based communities. There was … the group of kids that fluently spoke Spanish, and then there was the group of kids like me, where we were Mexican, we identified as it or Latin, but we didn’t speak the language,” she said. “We didn’t either speak it fluently, or some didn’t speak it at all, and that’s how we divided and aligned and made friends.”

Although the lack of fluency hindered Galbraith in social settings, she doesn’t hold this lack of teaching against her parents. While her parents had a different version of this story, her memory provides a different context. Sandra, Shante’s older sister, had to learn English when starting elementary school, challenging her ability to make friends. Sandra has since followed her parents’ footsteps, teaching her son English first with minimal Spanish.

“[My dad’s] whole reasoning for coming here was to have better opportunities,” Shante said. “In his perspective, making sure we spoke the native language … was the best way to give us [a] prime opportunity.”

Admittedly, Galbraith still feels a certain way about the missed opportunities from not knowing Spanish and never being fully embraced by the greater village, but that hasn’t changed her relationship with her immediate circle.

“Now that I’m an adult, I feel sadness because it’s such a missed opportunity,” she said. “But I never felt upset or angry with [my parents], because I got it. I got why they did it.”

So why didn’t she teach me and my brother Spanish? Was it because she wasn’t fluent herself? Not exactly.

“It was one reason, and it was not wanting your dad to feel excluded because…he’s not of any Latin descent,” she said.

This exposure to other ethnic groups and mixing is, of course, not exclusive to Latinos, but prevalent throughout this country, according to Tseng.

Tribulations aside, Galbraith also believes, like her parents, that your Spanish fluency doesn’t make you any more or less Latino, but it took her years to feel that way. Ironically, it was raising her own children without fluency that helped.

“I want you guys to feel welcomed…and that’s where I felt like I had to let go of the feelings that I had before and embrace the community,” she said. “It was never going to embrace me if I didn’t feel like I could genuinely embrace it.”

“Now that I’m an adult, I feel sadness because it’s such a missed opportunity, [but] I never felt upset or angry with [my parents], because I got it. I got why they did it.”

– Shante Galbraith

Photo Courtesy of the Villalpando family

No Sé, Not No Sabo

As a third generation Latino, this is often where the shift from Spanish to English as the primary language becomes the most apparent. The 2023 Pew study found that 65% of U.S.-born Latinos third generation or later can either only speak Spanish “just a little” or “not at all.” Tseng calls this a “three generation pattern.”

“We’re really seeing a pattern across immigrant groups in America where, within three generations, the language shifts to English,” Tseng said. “In fact, America is sometimes called a language graveyard because of that, which is rather sad.”

Of course, I’m not on this journey alone. My younger brother, Alex, grew up in the same situation of being a Latino with little knowledge of the native language. But would he face the same fears and insecurities as I do?

Despite being the older sibling, I learned more from him than he knows (but don’t tell him that). After our conversation, I started to realize something Alex already had: it’s not about the community as a whole, but who’s in your community. This line in the sand is not the same for everyone, so don’t try and satisfy everyone.

The openness and lack of judgement I receive from my village does not have to remain exclusive to them. There will always be those who are critical of my roots, but that does not change who I am. According to Dr. Tseng, I am a heritage speaker. Regardless of how much I know, it’s part of me. I used to question what I even laid claim to within my Latino identity. Now I know no one can take that heritage away from me.

As I carry on in my life outside of education and into the workforce, I may not bear as much pride as other Latinos, but that doesn’t alter my identity. That didn’t change my mother and her siblings. That hasn’t changed my brother. That will not change me.

All along, this child was being embraced by the village. He just didn’t know what it looked like.