In preparation for the week to come, Sunday morning trips to the grocery store seem like second nature to working-class residents. According to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, Los Angeles households rank food as their third most costly living expense, spending 13.6% of their budget on grocery trips and restaurants.

But for a large portion of Angelenos, when the budget is tight, food is one of the first factors to be affected.

“I’m a single mother and I’m a student and I don’t really work as much because UCLA is just it’s hard to do all of those things at once, so that’s why I am struggling now,” Karolina Prybula, a University of California, Los Angeles student studying psychology, said.

When Prybula’s weekly budget is tight, she turns to community food drives and nonprofit organizations for resources. She explained she is registered with CalFresh, also known as food stamps, yet still experiences difficulties feeding the two mouths within her household.

“It took quite a bit because there’s a lot of paperwork involved and sometimes the social workers that take care of the cases, they’re overwhelmed,” Prybula said. “The money still isn’t enough sometimes.”

Prybula just finished a weekly grocery trip to Ralphs, pushing her son in a stroller while smashing down her paper bags at the bottom. But once a month, on the other side of Sawtelle Boulevard, she waits in a line wrapped around the block for a local food drive pick-up.

Prybula’s financial limitations and experience with food insecurity are a narrative that is becoming increasingly common during an era where COVID-19 relief aid is rolled back, as well as state and federal resources are hard to come by.

Trends in food insecurity among low-income households in Los Angeles County

Sources: Los Angeles County Public Health, USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research, California Department of Social Services and Dr. Kayla de la Haye

Post-pandemic volatility and inflation

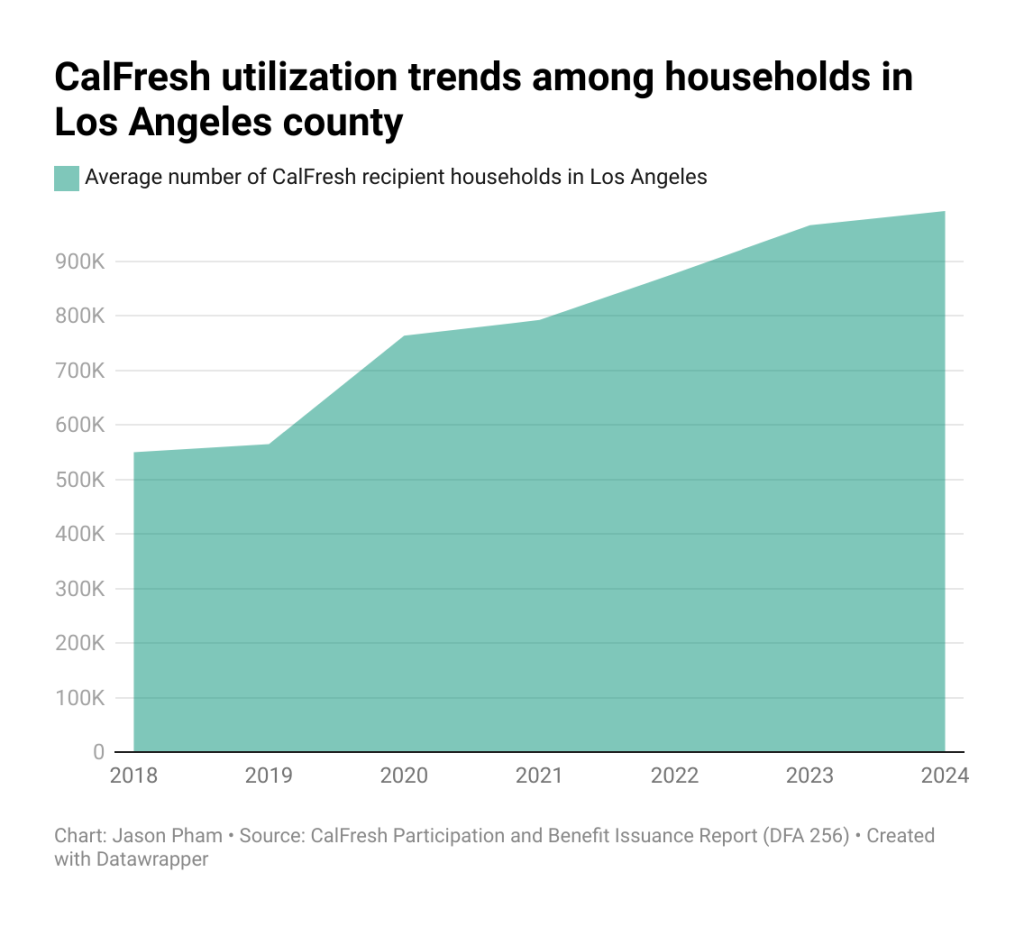

According to a study published by USC Dornsife, researchers believe Los Angeles has been in a “volatile” state since the onset of the pandemic, with a reported 42% of low-income households experiencing food insecurity in 2020.

As an initial emergency reaction, immense relief aid systems and a CalFresh benefits boost were pumped into the L.A. community to immediately address the fears and socioeconomic decline caused by COVID-19. And the response worked. Food insecurity levels among low-income Angelenos dropped to 28% in 2021.

However, these additional federal and state funds eventually came to a halt.

“People lost those extra boosts to their benefits [in 2022-2023],” said Dr. Kayla de la Haye, research professor of psychology and spatial sciences at USC and director of the Institute for Food Equity. “All of these extra resources got put into the local community but at that time were starting to get pulled back and that emergency money dried up.”

For residents who rely on CalFresh, like Prybula, these shifts in benefits and available resources make it difficult to keep up with daily groceries, especially while facing the after-effects of the pandemic.

“It’s really hard to prove my income and they would change my benefits, like I would have to call and when you call it just takes [a] really long time for them to answer the phone,” Prybula said.

According to USC Dornsife, food insecurity levels spiked to a whopping 44% in 2023 and mellowed out to 41% in 2024, one of the highest rates recorded since food insecurity started being tracked during the Great Recession.

Dr. de la Haye, who pilots and directs USC Dornsife’s annual food insecurity report, said she believes these fluctuating statistics are partially a result of tight financial restraint and disproportionate resources for various communities.

“Food insecurity really stems from, for people in households, a lack of financial resources and so all the things that put a community at risk for poverty contribute to that.”

Dr. kayla de la haye

research professor of psychology and spatial sciences at USC and director of the Institute for Food Equity

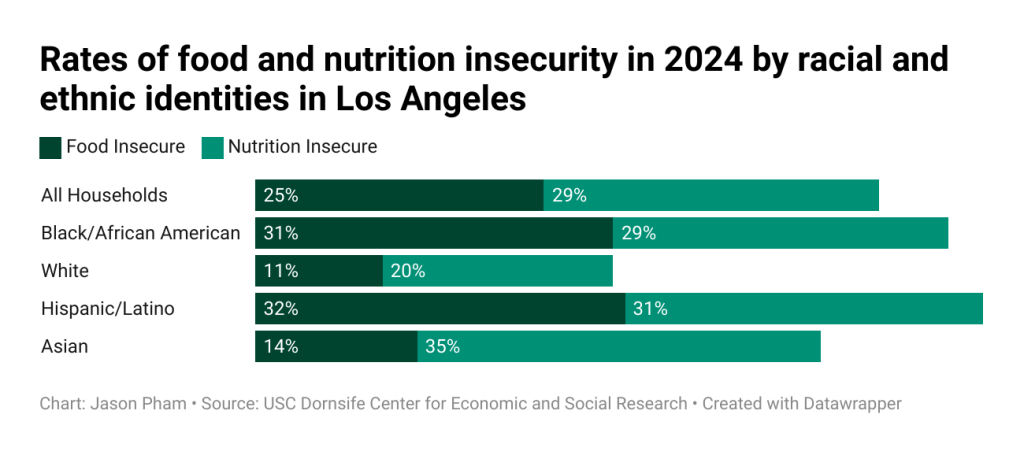

Food insecurity is an issue that especially affects not only low-income families, but also racial minorities and those prone to living in food deserts. In 2024, 76% of those who are food insecure are Hispanic or Latino and 59% are women.

“L.A. County has always had higher than national average rates because the people who live in our city are more of the types of people that are vulnerable to food insecurity,” Dr. de la Haye said. “We know Hispanic and Latino populations have a higher risk for food insecurity because of structural factors that have put them at greater risk for lower incomes and poverty.”

The lack of financial resources and shifting CalFresh benefits are not the only factors driving this new food insecurity narrative, as food and grocery price inflation is expected to hit skyrocketing rates in 2025.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, experts predict a 3.2% increase in all food prices, including a 5.2% increase in beef and veal as well as a whopping 57.6% increase in the cost of eggs. Although the overall increase in food costs is on average with yearly rates, egg prices are at an astronomical high, with some L.A. grocery stores selling dozen cartons for $9 or more.

David May, director of marketing and communications at the Los Angeles Regional Food Bank, said that the rising costs of eggs have deeply impacted the organization’s inventory and have been much more difficult to source.

“The economy and availability of certain food items is reflected in our inventory too. If eggs are hard for everybody, then it is also hard for us to come by,” May said.

May explains that the L.A. Regional Food Bank has funds set aside in case there is a need to buy certain food items or ingredients that are in high demand. However, he said this is typically a last resort and that the funds could go towards more cost-effective foods compared to eggs.

“We want to make sure what we purchase is healthy and is also food that can sustain people out in the community so then the question becomes if we start buying eggs then could that money be spent on other food that still provides those nutritious values to people out in the community.”

David may

director of communications and marketing at the los angeles regional food bank

Angelenos fight back

Despite climbing grocery prices and an increasing number of patrons, food organizations and non-profits still tread endlessly to ensure people’s peace of mind with food on the table.

Nourish LA is a nonprofit organization providing free recycled foods and hosting monthly food events for residents of Mar Vista and Venice. Established during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Nourish LA just celebrated its five year anniversary in April and is one of hundreds of organizations fighting the food insecurity crisis.

Natalie Blackner, CEO and founder of Nourish LA, said she saw a dire need for food supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic, tapping into her background in urban planning and waste management to address the growing issue within her neighborhood.

“I was in the L.A. moms [Facebook] group and saw all these parents asking for help with food, like right away because they’ve been laid off, their businesses were closed, all the different things,” Blackner said. “So I just got to work and I lived right next to a Whole Foods at the time, and put two pieces together.”

And the rest is history.

Nourish LA volunteers processes truck loads of recycled groceries by hand, carefully sorting through and inspecting each article of food to ensure it is safe for consumption and free of any mold or bacteria. (Photo by Jason Pham)

Nourish LA has grown to become a fully fledged 501c3 nonprofit organization with weekly food drives hosted on Sawtelle Boulevard where volunteers spend hours sorting and passing out groceries that were thrown away by local restaurants and grocery stores. These food items are typically discarded by mainstream corporations due to close expiration dates or deformed shapes, but are still physically safe to consume.

Nourish LA partners with FoodCycle LA to intercept food from grocery stores and reduce the amount of perfectly consumable food heading to landfills.

“If one egg got cracked in the dozen, all of those eleven eggs would’ve been tossed before, but this time we were able to intercept it, put it in a new egg carton, and give it to people who could use it.”

Natalie blackner

ceo and founder of nourish la

The nonprofit also hosts monthly events through their “Good Karma Project” initiative, where volunteers would plant food and turn a resident’s lawn into a community garden filled with vegetables and fresh ingredients.

“What we do really well though is that we’ve created an efficient system to providing people with lots of food in a short window of time because most of our workforce is volunteers and we have 75 volunteers helping out every single weekend to help us sort the food, clean the food, compost, recycle, and trash,” Blackner said.

During Nourish LA’s 5 years of establishment, the organization has reached and impacted the lives of thousands of Angelenos across the city, including Prybula.

Prybula said she frequents the food drive almost every week and appreciates the quality of groceries as well as getting the opportunity to meet others in her community.

“I don’t pick the meat but mostly vegetables, fruits, and maybe some dry foods that I can store and have for a different day,” Prybula said. “Food quality is good and I also like meeting new people in line so I make friends all the time when I’m there.”

Despite her limited options for ingredients at times, she said she thoroughly enjoys cooking various cuisines and experimenting with different recipes.

“I come from Poland, I grew up there, so I cook Polish food, but I love Asian food, I love Italian food. I cook everything,” Prybula said. “Recently, I just made spam musubi. That was the first time I ever made it and it was really delicious, so I cook all kinds of different things.”

With a line typically wrapped around the block and down the sidewalk every week, there is no debate as to Nourish LA’s immense impact and quality customer service satisfaction on the fluctuating food insecurity landscape.

But Dr. de la Haye questions if food drives are solving any long-term issues and if these high quantities in consumers are actually a sign of worsening conditions.

“It’s a band-aid if we keep giving people more food pantries or it’s a band-aid if we just give people one-off benefits for food. What we really need and what L.A. County is planning on doing is a whole transformation of our food system where healthier locally produced food is brought more into our community [and] it’s much more affordable for people,” Dr. de la Haye said.

Governing the future of food

According to Dr. de la Haye and Blackner, the city of Los Angeles is well aware of the food insecurity crisis, and community members are taking advanced action to fight increased obstacles like food inflation heading into the 2025-2026 fiscal year.

Blackner said Nourish LA is experimenting with and plans to expand into an online app, which focuses on connecting community members with restaurants and groceries offering recycled or price-reduced foods directly.

“The app has been running for two months and we were able to recover 10,000 pounds of food,” Blackner said.

The app is exclusively open to Nourish LA employees and volunteers at the moment, but Blackner said she aims to expand to the public in late 2025 and utilize the app as a stepping stone for more widespread food recovery projects in the future.

On the city level, Los Angeles County officially launched the Los Angeles County Office of Food Equity in November 2024 in order to combat growing concerns of food insecurity among households. The office will be dedicated to crafting comprehensive action plans to tackle food and nutrition insecurity, as well as connecting with local farmers and agriculture to ensure fair and affordable markets.

However, according to Dr. de la Haye, city efforts alone may not be enough to address the rising food insecurity crisis.

“The county is doing a lot and they have a strategic plan for the next ten years to strengthen our food system and make it healthier and more resilient,” Dr. de la Haye said. “But they really need to be bolstered by state and federal support and I think that is where we are really lacking.”

In February, House Republicans proposed a $230 billion slash in federal spending budgets over the next ten years for the Agriculture Committee, which oversees food aid programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

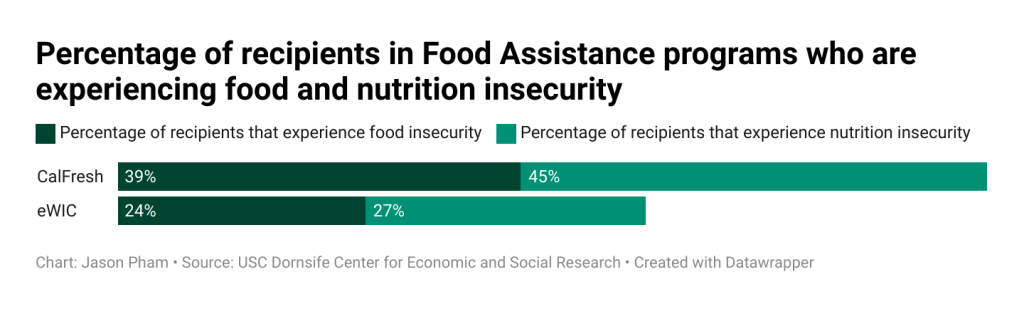

According to the California Budget and Policy Center, if the bill were to pass, daily CalFresh benefits could be reduced by 25%, or 1 in 4 food aid recipients could be stripped of their benefits entirely in order to abide by the proposed federal budget cuts.

“We are pretty terrified that food stamp benefits are going to get cut back in the coming months with this new administration,” Dr. de la Haye said. “There [are] a lot of folks who work on food issues in L.A. County who are pretty worried that we may have folks getting less money for food assistance in the coming months and we know that when people get less money for their benefits, that it puts them at much bigger risk for food insecurity.”