An increasingly sad nation

If you live in the United States, there is a one in six chance that you are among the millions of people who find themselves taking one or more psychiatric medications as a part of your daily routine. That’s according to a report by the Journal of the American Medical Association back in 2017, which said 16.7% of Americans reported regular usage of antidepressants and other psychiatric medications. Around this same time, the Center for Disease Control reported that a quarter of Americans taking antidepressant medication had been doing so for at least 10 years. But what if there were medications that only required limited doses which provided long-term benefits for depression?

Enter: Ketamine.

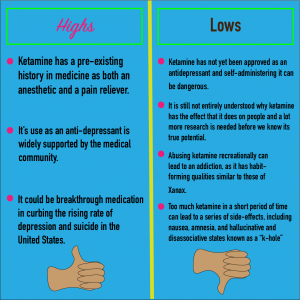

Ketamine is a medication traditionally used as an anesthetic, sometimes referred to as “horse tranquilizers” because of its veterinary use on horses. It’s relaxing, euphoric, and dissociative effects has also made ketamine a popular club drug known simply as “K” or “special K” in rave communities. Despite its traditional medical and recreational uses, new research suggests ketamine might be most effective as an antidepressant. As was reported earlier this year by both Harvard and Yale in their respective online medical journals, research on ketamine has shown that it can be effective not only at treating chronic depression, but actually eliminating its symptoms from some patients for extended periods of time. Ketamine isn’t just potentially a new antidepressant, some researchers think it may be among the most instrumental treatments doctors have seen for the mental illness.

One of those researchers is Dr. David Dadiomov at the University of Southern California. He spoke with me on what it is doctors currently know about the drug, and what information still eludes them.

Searching for answers

Inside a small two-person office at the USC Health Sciences campus sits Dr. Dadiomov. Papers and personal items outline the computer sitting on his desk where he spends much of his time. His trendy glasses reflect the bright white glare of the computer, contrasting against his dark brown beard and hair. While Dr. Dadiomov’s office might not seem like the source of innovative research, it is where the assistant professor of pharmacology has been unpacking the antidepressive effects of ketamine for over a year.

“What we have found is that a lot of the current solutions to mental health issues are expensive, they require daily usage and, at times, can be dangerous,” explained Dadiomov. “Here, we have an opportunity to find more successful and longer-term treatments which can not only reduce, but significantly alter the negative or uncomfortable ways in which a person’s mind is working.”

Dadiomov released his own findings on the effects of ketamine on suicidality in January of this year. His report found that, while there is still much to be studied in terms of the versatility of the drug’s effectiveness, ketamine showed dramatic effects in reducing severe depression and, possibly more interestingly, suicidal behaviors. It was noted in the report that one study of 82 patients showed that 55% of participants showed reduced levels of depression after their first ketamine infusion, a significantly larger margin than the 30% that responded to a sedative alternative. Dadiomov thinks that ketamine might be so much more effective because of the different ways it works on a person’s brain.

“Most [antidepressants] target monoamines, like serotonin, the neurotransmitter that allows us to experience things like happiness,” Dadiomov said. “What we’re seeing with ketamine is that it seems to take a different path to altering the patients’ state of thinking, where one dose can last for three weeks on a person before we see any kind of drop-off.”

Dadiomov’s research showed ketamine to have some of the most conclusive findings in reducing suicidality and self-injurious behaviors in people, a growing mental health issue in the United States.

Suicide rates rise as Americans are feeling low

From 2007 to 2017, suicide rates in the U.S. for people aged 10-24 increased by 56% with an average annual rise of 7%, according to the CDC. A report released by medical insurance provider Blue Cross Blue Shield suggested a 33% rise in major depression among people across the country since 2013, although their data is limited to only those with commercial health insurance. The report also suggested a greater rise of depression among younger generations.

“It could be a number of things that have gotten us to the point of being a more depressed nation, on average,” explained psychiatrist and psychotherapist Dr. Virginia Ayres. “For young people, especially, there is a lot of pressure these days, a lot of talk about ways they need to fix the world, and we live in very divisive times. When the world is presenting so much negativity, it can be hard for cultures to separate that negativity from their personal lives.”

Ayres specializes in child psychology and addiction treatment, giving her both hope and concern about the proposition of using ketamine for medical treatments.

“We have seen such incredible information come out about these things, and it really makes us want to hop on board and get this medication out to the world,” Ayres cautioned. “But we are still talking about drugs that people do abuse regularly, regardless of their addictive qualities, and we know that people will still abuse their prescriptions, so we have to be really sure about what they are and how they work before they make their way into the pharmacy.”

And ketamine is not the only recreational drug being studied for the treatment of mental illness.

Psilocybin: The magic in mushrooms

Psilocybin, the psychedelic compound produced by over 200 species of mushrooms commonly known as “magic mushrooms” or just “shrooms,” has been receiving a lot of attention recently for its potential effects on people experiencing severe depression and anxiety. In 2000, Johns Hopkins received regulatory approval to study psychedelics, creating the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, currently the leading voice on these substances in the United States. Their findings have been the most comprehensive on the subject, involving trials with everything from using psilocybin to reduce terminal cancer patients’ severe anxiety surrounding mortality, to its use in curing nicotine addiction, two trials which have shown promising results. In the studies on psilocybin’s use to quit smoking, researchers reported that the 15 participants in the trial had an 80% abstinence rate over six months, compared to the 35% success rate of verenicline, which is commonly considered to be the most effective smoking cessation drug. While researchers are excited about these results, their still remains concern about psilocybin’s potential short-term side effects, which can include nausea, dizziness, and paranoia.

While these ongoing clinical trials are paving a legal route for the acceptance of medical psychedelics, there are only a limited amount of spots available for study participants. But that does not mean university labs are the only places where similar forms of treatments are taking place.

The psychedelic integration therapist

A quaint suburban home in Chino Hills, California, houses a family with deep ties to the subject of psychedelic therapy and medicine. Shelves decorated with various cultural tools and means of alternative medicine from across the globe tower over the floor littered with childrens’ toys and decorative pillows. This decor is appropriate for the location, considering the house doubles as both the family home and main office of “psychedelic integration therapist” Sherree M. Godasi.

While Godasi cannot administer the drug to her patients, she can offer them weeks of mental and emotional counseling and preparation for a psychedelic experience and continued counseling afterwards.

“I have seen the transformations that happen with people when they do have the proper, thorough preparation and ongoing long-term integration on the back end and it’s really, really amazing,” Godasi explained, sat beneath psychedelic paintings on the wall.

Godasi is not authorized to administer psilocybin to any of her clients, nor is she legally allowed to make herself or her home a source for the use, distribution, or cultivation of any illegal substances.

For clients of this type of therapy, it becomes even trickier as they are the ones who must actually perform the crime of acquiring and ingesting the substance.

An anonymous patient of underground therapy

Sitting across from me in a Santa Monica townhouse is a woman who seems to be about as anxious as she is excited to have our conversation.

“I’m Canadian,” she explained to me over the phone a few days before our interview. “So I don’t think I should be on the record with my name, because I’m afraid I could lose my visa or something, but I really want to talk about this.”

She provides me with her preferred pseudonym of “Mojo,” an appropriate alias for the charismatic northerner. Her mostly minimal space is decorated with spiritual and meditative trinkets and tools, the leather chair she’s sitting in, and a bookcase housing Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind, a thorough account of the medical and introspective benefits of psychedelics.

“I came to psychedelic psychotherapy during a divorce,” Mojo explained, gripping the arm of her leather chair. “So, as I was dealing with all the emotions that go along with that, in the midst of my grief, I decided to search on Amazon for how to change myself and how to change my mind, and Michael Pollan’s book came up.”

Inspired to try what Pollan had written about, Mojo began her journey into this new form of psychotherapy, though she had plenty of experience with traditional therapy before. She explained that she has been in and out of cognitive behavioral therapy most of her life, because she believes “if we go to the doctor for broken arms and colds, than we should go for any kind of existential ennui.”

“I don’t know that I can articulate what wasn’t working with that kind of therapy,” Mojo said after a deep breath. “But, in hindsight, it seems like traditional talk therapy was meant to make you feel better in the short term but never got to the root of the issues, it felt like it was a band-aid approach rather than a deep healing.”

Her process in psychedelic integration therapy involved four weeks of talk therapy and then, eventually, she took the psychedelics when she could draw from the therapy during her experience. She experienced in this session something which many people report after taking psychedelics, both medically and recreationally, being the ability to clearly observe patterns in one’s own life. According to Mojo, she saw patterns in her own view of life, noting her tendency to over-intellectualize or over-analyze things, as well as patterns in her relationships with others, both romantic and platonic.

While she claims this therapy has changed her life immensely for the better, she is still hesitant to recommend it to people on account of the legal issues surrounding it, as well as the unknown elements of the drug and how it affects people differently. Still, she is an avid supporter of the practice, one which helped her through one of the hardest times in her life when all she wanted was to end the heartbreak.

It’s been a year and three months since Mojo first started this form of therapy, and she has since joined the broader Los Angeles psychedelic community, frequenting meetings and events on the subject, some of which she considers to be “necessary” resources to exist. This community she joined is called PsychedeLiA: Psychedelic Integration, which was founded by Godasi in her attempts to overcome the stigmas and legal caveats surrounding her work.

PsychedeLiA

“The whole idea of PsychedeLiA is to promote connection between community members, to provide educational tools and emotional support, that’s really the mission of the organization,” according to Godasi. “In a very acute way, integration is really all about community. One of the main lessons of psychedelic healing is that we all come from the same source, we are all in this together and it is all about connecting to ourselves and others so we can take better care for ourselves, for each other, and for the planet, and it’s through community that we can do that.”

Although Godasi recently stepped down as the chair of the organization in order to make room for new leadership, she still remains on the board as it transitions into becoming an official 501(c)(3) non-profit organization.

Barriers to acceptance

Prior to its criminalization in 1970, psilocybin was being researched for its use in the field of psychiatry, with Harvard University as the testing ground. A rise in the popularity of recreational use of hallucinogens in the 1960’s caused the government to ban all drugs which fit under that blanket category, including psilocybin and Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD). They were labeled Schedule I narcotics, meaning they have no accepted medical use and show a high risk for addiction. That status means researchers must have very conclusive findings on the drug’s effects and uses, should it ever be accepted as legal medicine.

Johns Hopkins is fighting this, however, arguing in its most recent project that psilocybin should be reclassified from a Schedule I narcotic to Schedule IV, with medications like Xanax and Ambien. Ketamine is currently a Schedule III narcotic, along with anabolic steroids and Tylenol with codeine.

There is still much more research to be done before we know if these substances will make their way into mainstream medicine, Dadiomov believes rising rates of depression and suicide call for a sense of urgency in helping the country restore its mental health.

“I think it’s much needed, there are so many patients that just don’t have an adequate solution to these things. You have to tread carefully, and not think these substances are just going to solve all these problems, but there is something interesting there that I think we, as a medical community, need to explore further.”

1 reply on “Americans are getting more depressed. New research suggests ketamine and ‘magic mushrooms’ could be a solution.”

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.