Immigrant Detention

I was never really a superstitious person. Until this very moment. Sure, I would wish on fallen eyelashes about a test, a boy I liked, or what direction to take on a hiking path. But never for my life, with a stranger, like this moment…

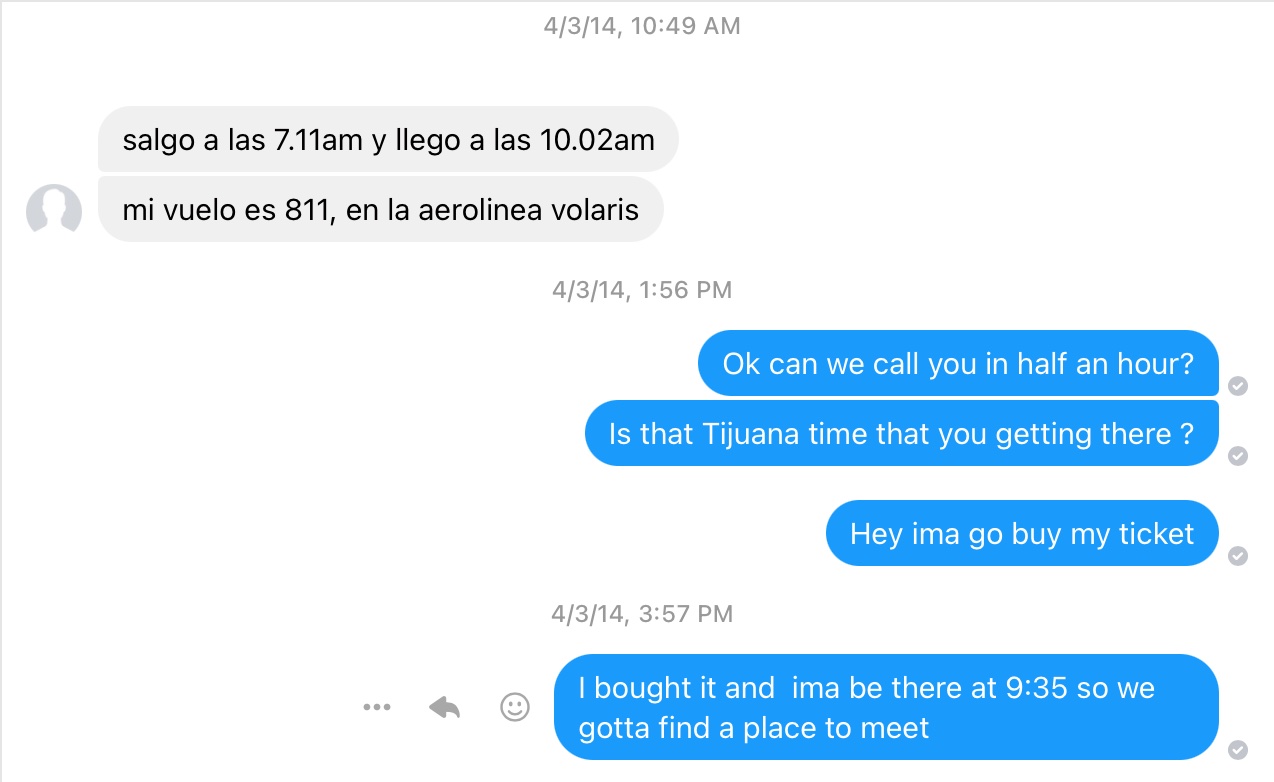

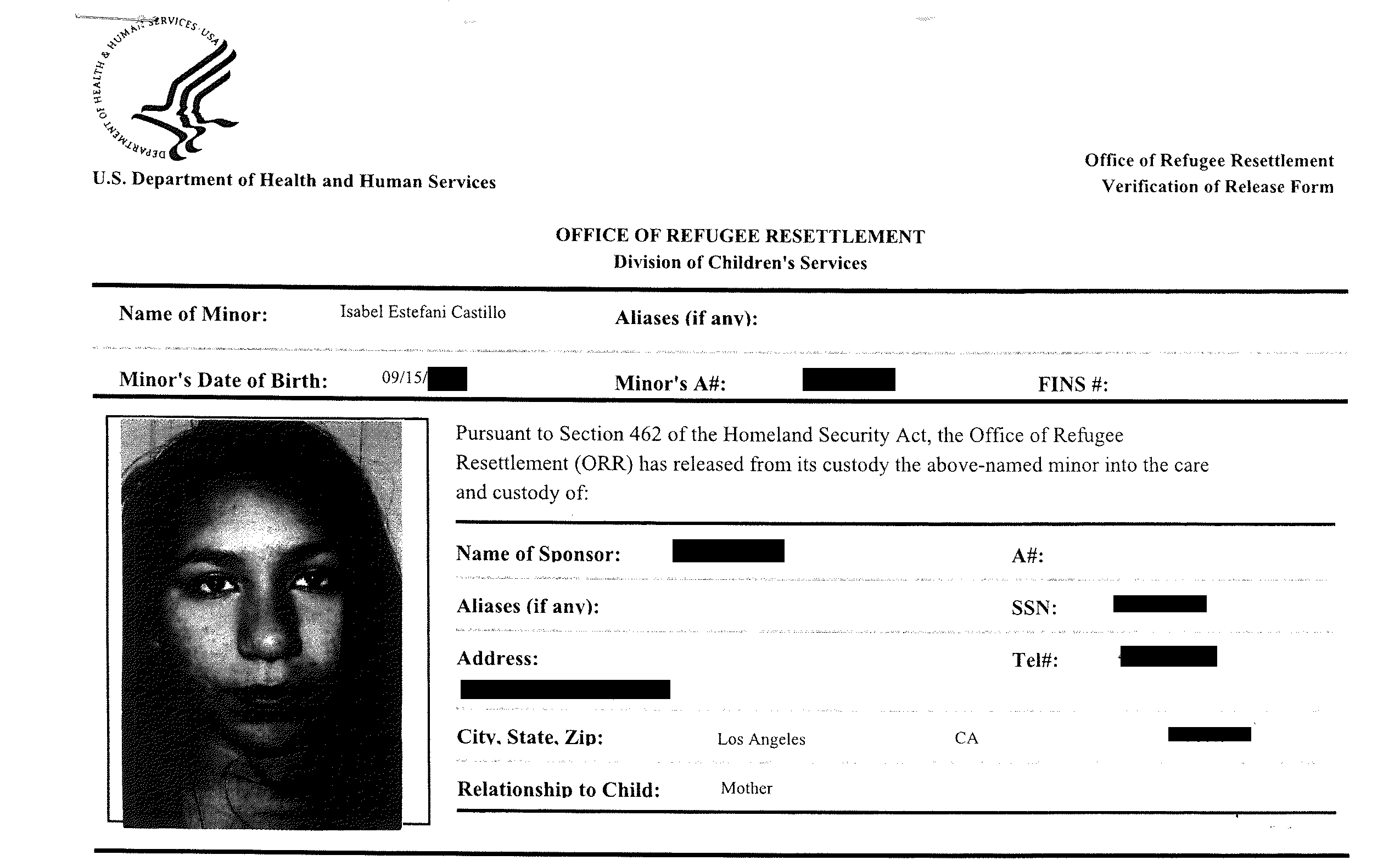

Click on picture to view document

Just seventeen years old, I wished to go back to my bed, my friends, and my senior year of high school. But five minutes later, a guard called our names and we left. Me and my fellow cellmate Estefany, a year younger, were put in a white Ford Explorer with the ICE logo on each side. The awful four days of detention at the border were finally coming to an end, but we didn’t know it yet.

With no explanation from the guards or resistance on our part, we boarded the car with two lunch packs like the kind you get on field trips in elementary school. In the back seat, behind a plexiglass shield, I held hands with Estefany. She had never been in the U.S., but because I was raised there, I was able to figure out where we were going. We departed from the San Ysidro border, onto CA-57, and stopped at a San Diego Court House, all without a word of explanation. Thoughts raced through my mind. I was terrified of being deported and never seeing my family again.

I was one of the 68,541 unaccompanied alien children, as the U.S. government calls us, detained in 2014. In the first 11 months of the 2019 fiscal year, that number rose to 72,873, a record all-time high, according to the Congressional Research Service.

In the past decade, the number of unaccompanied minors has risen slowly, with two peaks in 2014 and 2019. (These numbers don’t include children separated from their parents as part of the Trump administration's zero tolerance policy toward immigrant families.)

Those figures include young people under the age of 18 who aren’t authorized to enter the United States and aren’t with a parent or guardian when apprehended by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers, or who turned themselves in at a port of entry.

In a 2019 report, The Congressional Research Service found that crime, economic conditions and opportunity, poverty, transnational gangs and reuniting with family contributed to the rise.

First Encounter With The American Dream

My immigration journey began in 2002 at the age of six when I boarded a plane from Lima, Peru to come meet my “aunts” and brother in the U.S. Upon arriving here, I was told that one of my aunts was actually my mother, who had fled Peru in part to escape the stigma of being a single parent. Los Angeles became my forever home.

I quickly adjusted to life in the United States. My mom supported us by cleaning houses and sewing in her free time. I didn’t think much about immigration until 2007, when my brother was a senior in high school applying for college. Back then, California universities and colleges only gave financial aid to legal residents. We have always been below the poverty threshold, so he knew my mother couldn't afford it and gave up his senior year of high school. My disillusioned brother returned to Peru. Because we all came on tourist visas, he would have to wait 10 years in order to file for another visa, and because he had overstayed in California, getting another visa would be nearly impossible.

In Peru, by the end of 2013, my brother had grown fearful for his life. He was being publicly shamed and beaten for being gay—prompting our family to look for another option.

My mother furiously watched Spanish language news and searched the internet for a way to have my brother return. Univision, her main news diet, showed young adults with caps and gowns presenting themselves at the border hoping for entry. They wanted to apply for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which offered two-year relief from removal and work authorization for undocumented immigrants who came to the United States as children.

Picture of my DACA in 2013

My mom hoped my brother could do the same. But these young people, and my brother, were in a different situation than I was. They had left the U.S. before the Obama Administration created DACA, although they were eligible. Now they were returning in the hopes they could receive it. My brother was in the same position. But I wasn’t. My DACA authorization had been approved in 2013.

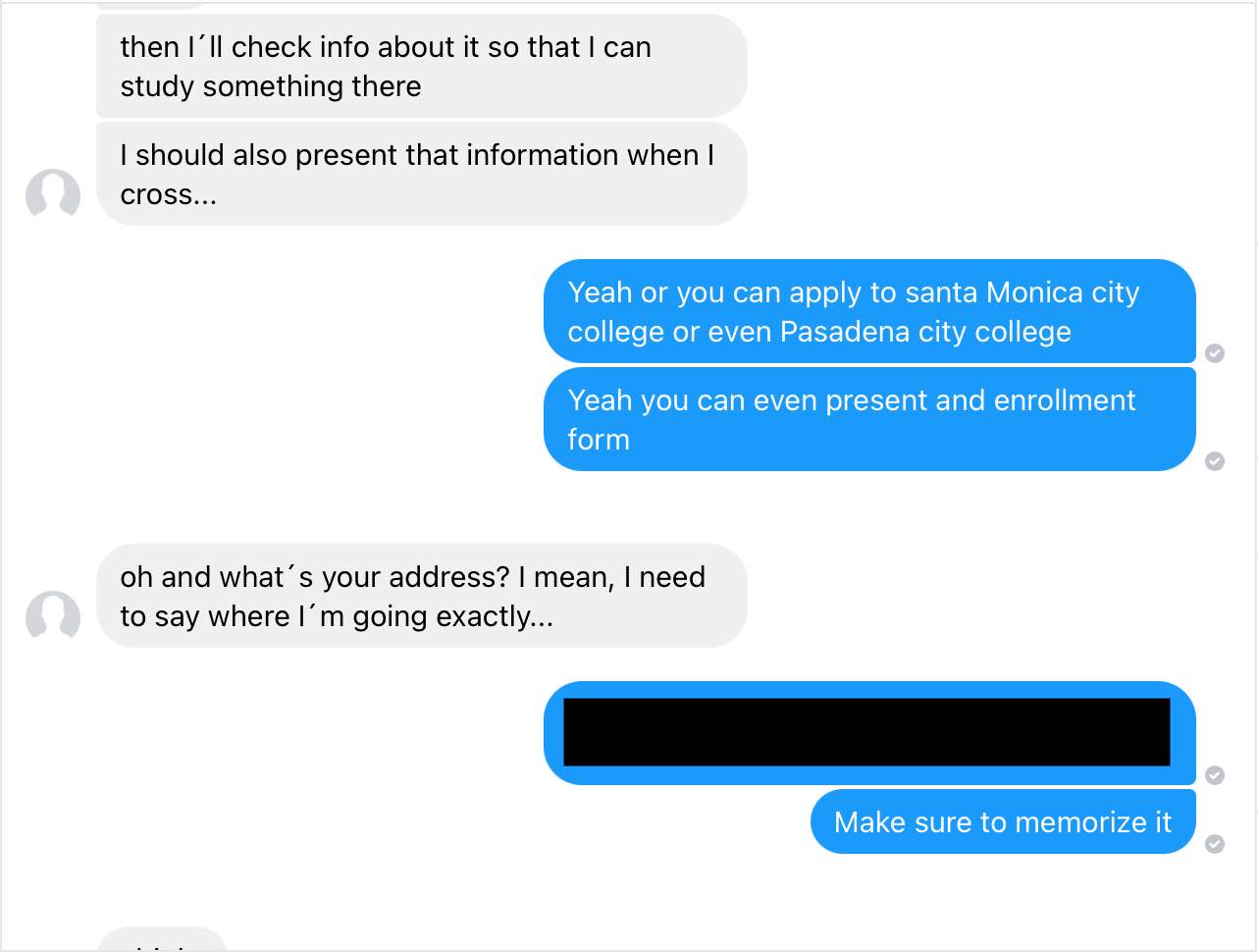

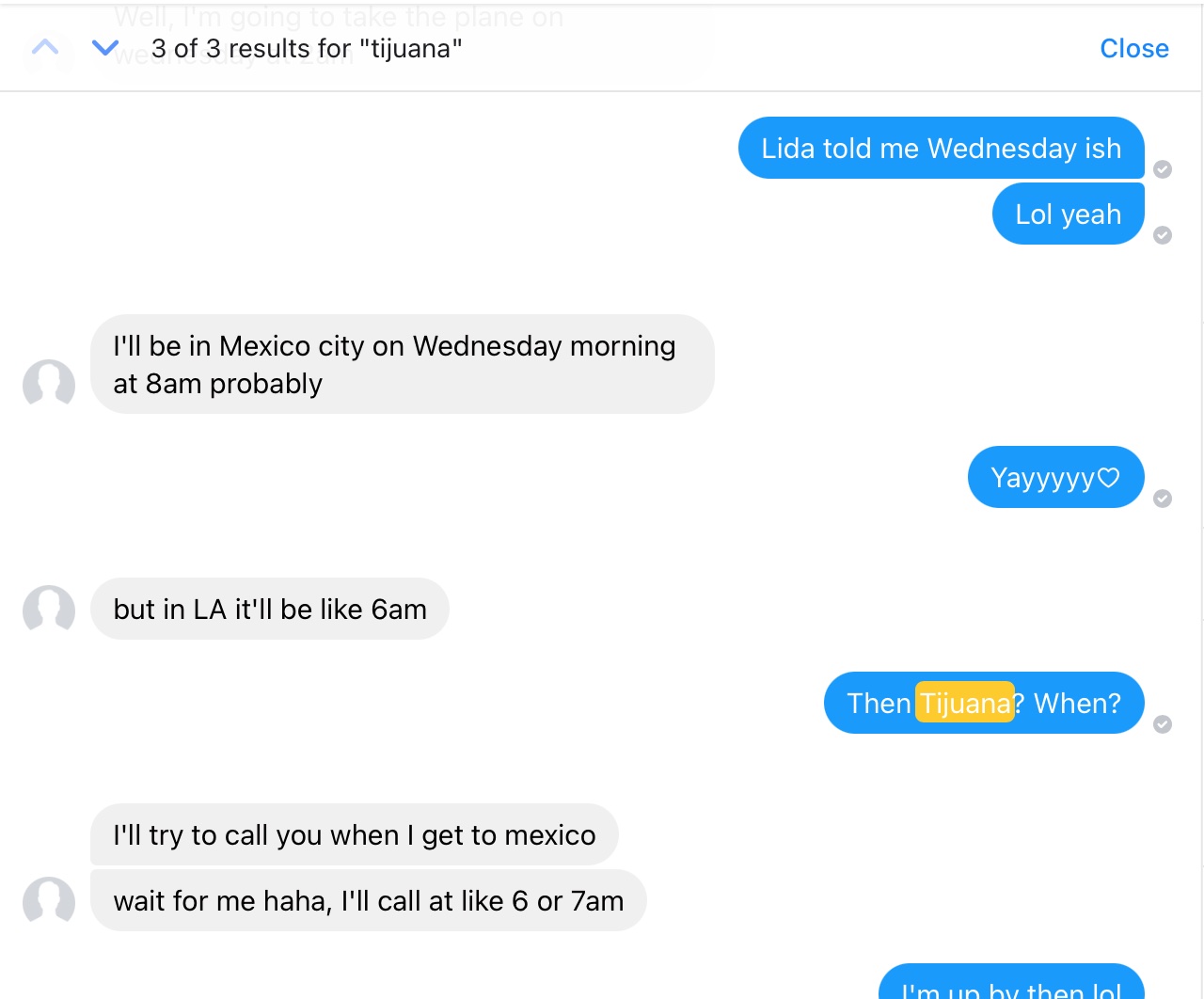

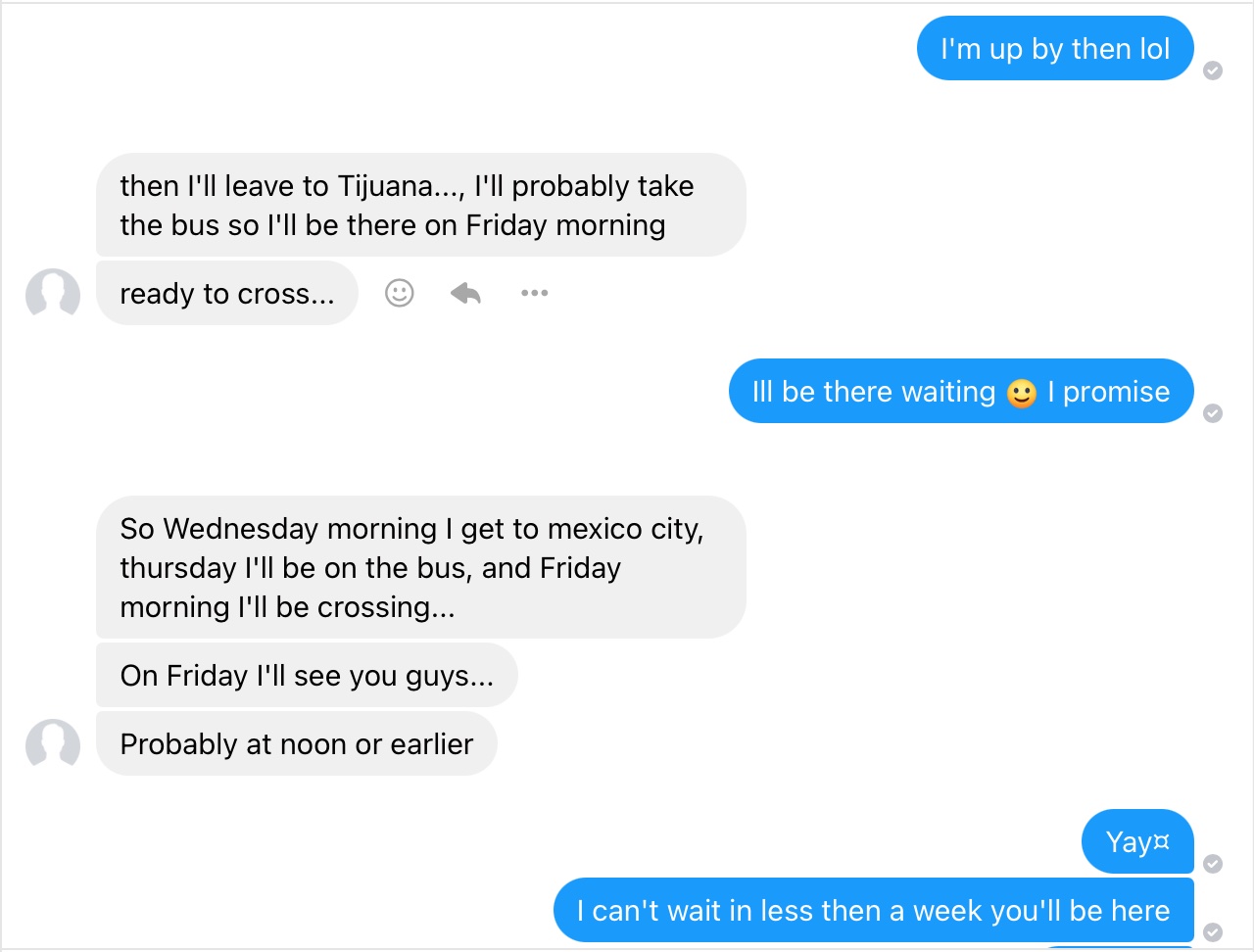

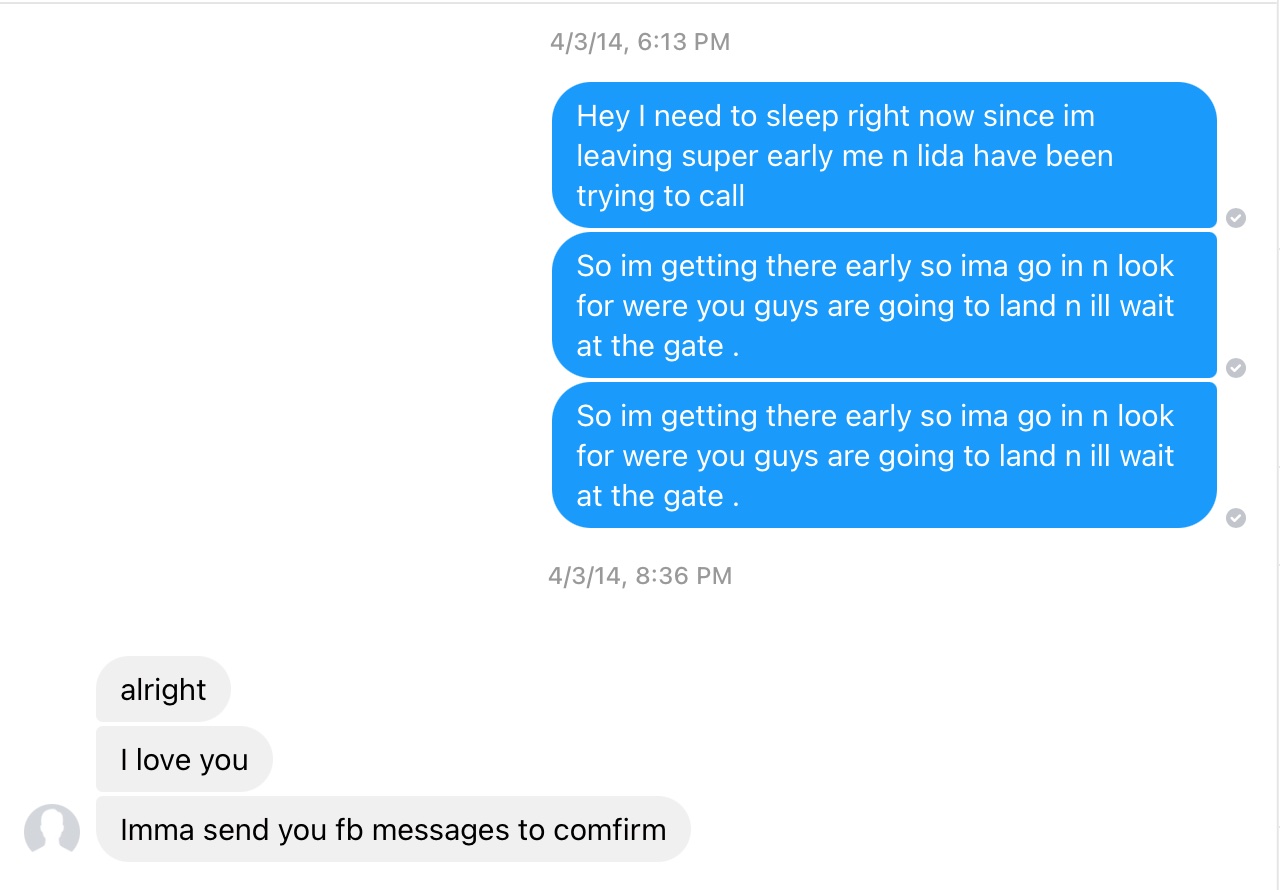

When my brother landed in Tijuana, in April 2014, my mother insisted I go join him to help with his application for asylum. So I took an exhausting six-hour Greyhound bus from Los Angeles to the San Ysidro border. I believed the process would be quick and I would be home later that night.

After meeting up with my brother, we waited four hours in line to present ourselves at the San Ysidro port of entry on the border between Mexico and California where my brother asked for political asylum. Naïvely, we believed he could ask for asylum and be let back into the United States right away. As we waited, we made plans to watch “Divergent” at a nearby movie theater. I caught him up on the years of my life he missed.

“Hello sir, we are looking for political asylum in the U.S.,” I said.

Our conversation stopped near the front of the line as we got closer to the guard. We held hands and I acted as our spokeswoman.

“Hello sir, we are looking for political asylum in the U.S.,” I said.

The officer asked us for documentation for our entry. I presented him my DACA and my brother presented an expired Peruvian Passport—documents not valid for entry to the U.S. Because of this, he deemed us inadmissible, took our belongings, and led us to an office past the rusted metal turnstiles.

Officers can deny entry to the U.S. for many reasons—health, suspected criminal activity, fraud, and several others. In our case, it was for lack of proper documentation.

My brother and I were led to an inspection room with a female officer and three male officers, our hands behind our backs as instructed.

“Cual es tu fecha de nacimiento?”, ‘What is your birthday?’ the woman sternly asked me. I shyly replied as she screamed at me in Spanish, “Do you not know your birthday?”

She kept asking me questions to verify my identity, even as a male officer frisked me for what felt like a half hour. He caressed my hair and ran his hands over my torso and breasts and finished by quietly groping my butt as he left the room.

Afterward, they led me to a line of brown plastic chairs in front of a white wall, separated from my brother who sat on the other side of the room.

We sat there as hours crawled by. All we could do was look at the wall, because if anyone glanced around, a guard would scream at us to keep our heads straight. As time passed, more people joined us in the waiting room.

I was called to see an officer once more. He asked me why I went into Mexico from the U.S, and I remember thinking of what my mom had told me to say. “I want to help my brother seek asylum,” I said.

After laughing at my response and calling me “estupida,” he asked me for my mother’s number before sending me back for more hours of staring at the blank wall. After some time, my brother, 21, was taken into an adult male cell. Shortly after, they took me to a cell for minors.

Without knowing it, we had entered, “La Hielera,” the ice box.

Life In "La Hielera"

That’s where I met Paty Magaña, a friendly 14-year-old Mexican resident traveling with her 9-year-old brother Mateo. Later that evening, in the middle of the night, we would be joined by 16-year-old Estefany Umana, from El Salvador.

Paty's shelter intake picture

Paty was from Apatzingán, a small town 300 miles from Mexico City plagued with organized crime, drug lords and unresolved homicides.

Paty says her neighborhood was run by drug lords and gangs. She recalled one morning when she saw her classmates’ heads hung up on a nearby monument on her way to school. When her brothers Mateo and 17-year-old Armando began being recruited by nearby gangs and drug lords, they decided to reunite with their parents, who had emigrated to the US in 2010. Their father had decided to leave Mexico after he was almost killed by a gang member while driving a municipal bus. Paty and her siblings had stayed behind, sometimes alone at their home and sometimes with family members.

After those confrontations, Paty and her brothers packed their bags and traveled 28 hours by bus to the San Ysidro port of entry April 2, 2014, a day before I did. They hoped to reunite with their family in Washington state, assuming, naively, “It would just take a day or two.”

Federal law requires that children under Border Patrol custody can stay no longer than 72 hours in “La Hielera”—called processing centers by CBP.

While in “La Hielera,” the ice box, Paty entered survival mode to protect her younger brother.

“Paty, when are we getting out to see mommy and dad?” her little brother Mateo asked.

“Paty, when are we getting out to see mommy and dad?” Mateo would ask. Paty replied that she didn’t know, and they just had to be patient. Through uncertainty, confusion, and exhaustion, Paty tried to keep her spirits up even as the guards were trying to encourage them to self-deport back to Mexico.

Young people from Mexico and Canada, contiguous territories whose borders are next to the U.S. go through a rigorous initial screening process at the border. That process determines eligibility for asylum seekers. If they don’t qualify, they are ‘voluntarily returned’ to their country.

Many guards encouraged us to self deport.

The day after I was detained, guards called me in at 3 a.m. for interrogation. We spoke in Spanish. A Nigerian girl who I had met earlier had warned me not to sign the voluntary deportation papers, so I was vigilant.

Before the formal interview began, the guard told me my immigration relief application would be denied, and encouraged me to self- deport. I remember feeling like that was impossible. I felt more American than Peruvian. I declined, and we began the interrogation.

A short time later, the guard handed me a pile of papers in English, demanding I quickly sign them. Few of my fellow detainees spoke the language, and I had hid my own knowledge at first, keeping it to myself that I understood their frequent insults in English. When I saw the voluntary return papers, I let him know I understood English and I would not sign.

When I returned to the cell, I told my cellmates to try and read everything before they signed.

When Paty remembers our time in “La Hielera”, it makes her emotional and sad.

“It was terrible not eating, showering, or sleeping because of how scared we were of the outcome,” she recalls.

Paty and her brothers left the “La Hielera” April 9th, 2014, six days after they turned themselves in at a port of entry.

In 2018, the ACLU released a report, charging that records about migrant children under CBP custody between 2009 and 2014 “ document a pattern of intimidation, harassment, physical abuse, refusal of medical services, and improper deportation.”

CBP called this report,“unfounded and baseless.”

Our holding cell was more comfortable than those of the adults. Instead of sleeping on the cold ground, we had black gymnastic mats. To entertain some of the younger children, they had a TV behind a glass window playing the Beauty and the Beast on replay constantly. We had some sort of white baby gate door with a clipboard on the right to keep track of any new inhabitants.

Still, “La Hielera”, was a cold terrifying place for Estefany, Paty, and me.

Estefany arrived to “La Hielera” at 3 a.m. on April 5th. Because she arrived so late, they didn’t give her any food or blanket to cover herself for the night. When I saw Estefany shaking, I motioned her over to share my gray, military-style wool blanket.

Estefany in 2014 before she turned herself in at a port of entry

I introduced her to Paty shortly after and that night, the three of us huddled through the cold and fear. We helped one another get past those gruesome days of uncertainty.

Over the three days we were there, Estefany told me about her journey, traveling by foot and on buses for more than three months before she turned herself in at the San Ysidro port of entry.

Now 16, Estefany had grown up in the city of Santa Ana, 70 miles from El Salvador’s capital, San Salvador.

After her mother died in a car crash when Estefany was three years old, she was raised by her grandmother and her uncle. Her grandmother, a U.S. resident, would travel to the U.S. for six months at a time, leaving Estefany alone to fend for herself or with help from her uncle.

In 2010, her uncle, who raised and sold livestock to nearby drug lords, was killed in front of Estefany following a misunderstanding with a client.

“That moment I promised myself that I would save up money to move to the U.S. and be safe,” Estefany recalls in a phone interview. “I saved up 4,000 dollars in three years to make my journey.”

“Sitting there with you and Paty talking about the U.S. made me feel hopeful for the future,” she told me recently.

Estefany and I were ultimately taken to a shelter called Crittenton, a co-ed group home in Fullerton, to await a legal guardian to assume our custody. Because Paty was traveling with her three brothers they went to a co-ed group home, Boystown, in Miami Florida.

Under the Homeland Security Act of 2002, Congress transferred responsibility for unaccompanied minors to Health and Human Services from the former Immigration and Naturalization Service, to help in “ensuring that the interests of the child are considered in decisions and actions” relating to their care and custody.

Unaccompanied Minors Released To Sponsors By State Fiscal Year 2014

My first memory at Crittenton was getting out of an ICE SUV with Estefany and feeling exhausted, but still scared. Once our intake was done, we went to the dining room to eat our packed lunches. As I took a bite out of a cold sandwich made of white bread, bologna and American cheese, tears rolled uncontrollably down my cheeks.

One of the women working at the home commented, “I bet you she hasn’t eaten anything better than that.”

It had been four days since I had a bite to eat, or anything but Strawberry Kiwi CapriSuns. Most of us in "La Hielera" didn’t eat...

She was right, but that was because it had been four days since I had a bite to eat, or anything but Strawberry Kiwi CapriSuns. Most of us in "La Hielera" didn’t eat because they gave us moldy, spoiled, or burned food. I didn’t cry because I was hungry. I cried because I would finally be able to take a shower, sleep on a bed, and know the time.

I stayed for 20 days, until my mother came to get me. Estefany stayed for a month before boarding a plane with her case worker to meet her aunt in Falls Church, Virginia. Paty and her siblings also stayed for a month in the center in Florida before reuniting with their parents in Yakima, Washington.

I didn’t know much about my brother until I was released. He was taken to Eloy Detention Center. There, he was chained hands and legs for 40 days until he was released on parole. After he entered the U.S., he struggled with anxiety and depression, and turned to methamphetamine to cope.

The Eloy Detention Center did not respond to my request for a comment on my brother’s stay. I reached out to CPB to comment about my own experience, but a spokesperson also declined.

In 2014, the Office of the Inspector General conducted an investigation into conditions for unaccompanied minors following reports of abuse, The report said observers “did not observe misconduct or inappropriate conduct during our unannounced visits.”

In 2016, a Congressional subcommittee criticized the government’s handling of unaccompanied children.

In 2019, The New York Times reported the government received over 4,500 complaints of sexual abuse involving minors held in detention centers between 2014 and 2018. In the article, the agency in charge of caring for those children said all complaints had been investigated and the safety of children was their top concern.

Life In The Dreamland

After being released to the care of our family members, Paty, Estefany and I began legal proceedings in our respective states. These would go on for years.

Soon after I was released to my mother’s care in June 2014, we found a pro bono lawyer named Ailin Buiges, who represented me until 2018.

I’ve had infants as clients.” Buiges said. “Their feet literally hang from the chair and the judge asks, ‘do you understand’...

Buiges co-founded the Immigrant Defenders Law Center in Los Angeles and is now the associate director of the Unaccompanied Children program at the Center of Immigration and Justice at the Vera Institute. Her remarks reflect her personal opinions, not that of her employers.

“I’ve had infants as clients,” Buiges said. “Their feet literally hang from the chair and the judge asks, ‘Do you understand?’ It’s like the child is being interrogated.”

Defendants are given due process at an immigration court. However, many of them represent themselves because they can’t find or afford a lawyer

According to a decade long Syracuse University study, nine out of 10 children without representation in immigration removal proceedings were deported.

These proceedings are not easy, but we all had lawyers and it still took years for some of us to hear back.

Estefany’s proceedings were the shortest.

Being an orphan helped qualify Estefany for a Special Immigrant Juvenile visa. Three months after she was released from Crittenton Estefany received the Juvenile visa. One year after it was approved, she received her green card.

Paty and her siblings applied for defensive asylum citing credible fear of persecution by local gangs and drug lords.

The process of asylum is complicated. Buiges says Unaccompanied minors can choose to submit their asylum application to the immigration courts or an asylum office.

“One of the reasons why they created this sort of protection to kids is because it's non-adversarial,” Buiges said. “It's supposed to be a little less serious, you're just in a room being interviewed by an officer and you don't have a government attorney cross-examining you.”

However, unaccompanied children’s fate in the U.S. is dependent on that officer’s cross examination. Buiges says it can lead to arbitrary decisions.

Paty’s asylum application was approved in 2016, and she is now in the process of obtaining residency, but both of her brother’s applications were denied.

“We both had the same experiences, but my brothers didn’t go into as much detail as I did so that’s why we think their asylum was denied,” she said. Her brothers are in the process of appealing the decision. Paty hopes that they too are granted asylum so that their journey was not in vain.

Buiges says many factors go into a ruling on asylum. She says she often can’t predict what made an officer deny a client’s application.

“It's not just what's in your declaration, or what's in your application,” Buiges said. “A lot of it is: how did the interview go, what did you say in the interview, were you able to corroborate everything in your declaration, did you have any credibility issues.”

Buiges helped me file for a Special Immigrant Juvenile Visa. My case was denied because I was two months shy of my 18th birthday and my dad wasn’t served the court papers.

Reflections After Detention

So, was this journey worth it for all of us? The answer is a resounding yes.

Paty and her husband David, September 2017

Paty met her husband David, who became a naturalized citizen ten years ago, in high school. Paty is currently working at restaurants as a server and cashier, and David works in a warehouse. They are working on building a life for themselves there. Paty is about to apply for residency and is looking to becoming a makeup artist. She hopes to one day return to school to become a psychologist.

Estefany is in the process of applying for citizenship and gave birth to a son a few months ago. She and her husband moved to Brooklyn Park, Maryland. Before giving birth to her son, she was working as a waitress. Her husband is a carpenter.

It’s been a long hard journey. Since moving to Los Angeles, I have felt in limbo. It almost feels as if I have one foot here in the States, and another back in Peru. I understand we didn’t follow the rules, but I was too young to make my own decisions the first time we came. The second time, I was older, but still found it impossible to resist pressure from my mother. I made a mistake and I paid a high price.

Current talk about immigration includes critics who think immigrating to this country is easy and people come to take advantage of the system.

Buiges believes the system needs to be re-envisioned.

“We have created this idea that if you are fortunate and lucky enough to be on one side, you are now entitled to all these amazing protections and future, the American dream, but if you are born on the other side, that you have to do things the right way to get in and have access to that dream,” said Buiges.

2003, L.A. with my Grandma

As an immigrant herself who now contributes to her community, Buiges thinks we need to look at immigrants as more than a commodity with no value, shifting that lens to helping support them to become contributing members of society.

“I think you're a perfect example where you have contributed to this society,” Buiges told me.

I don’t see myself as coming to take advantage of the system. I was brought to the U.S. at a young age and I want to contribute to society.

That is why I am finishing a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Science in journalism at USC, so that I can become a multimedia journalist who continues telling stories of the voices that are unheard. In August, I received my work permit and now I can finally dream of a life where I don’t have to work under the table after graduation.

Since 2014, a lot has changed at the border. The Obama administration’s second term saw an influx in unaccompanied children migration. The administration successfully pushed for an extra $4 billion to tackle the border crisis. It also approved a $2 million program to fund free legal services to unaccompanied children via AmeriCorps.

With limited shelter space, the administration began placing unaccompanied minors in military bases, and then transitioned to holding children in temporary holding enclosures—also known as cages.

When President Trump took office in 2017, he categorized unaccompanied children as “opportunistic” and cut down their protections. His “zero tolerance” immigration policies slowly stripped unaccompanied minors of essential protections.

Shortly after Trump took office, the Department of Homeland Security began a pilot program, separating families at the border, to deter future asylum seekers. A month later, the Department of Justice terminated free counsel for unaccompanied children. In November 2018, the child refugee program that let children apply to refugee status from their home country was terminated, forcing children to make the dangerous journey to the border.

His administration has also made it more difficult for abused children, asylum seekers, and those seeking fee waivers, and removed protections for children who turn 18 in their care.

On November 18, 2020 a federal judge ruled against the Trump administration’s process of turning away children at the border, as public health risks, before they could request asylum. Earlier this year the administration turned away nearly 9,000 unaccompanied minors at the border citing that the CDC guidelines for the COVID-19 pandemic override the protections of children.

In my opinion, both administrations did an abysmal job caring for the safety and wellbeing of unaccompanied minors in their care. Following my time in care, I was diagnosed with anxiety and panic disorder. Sometimes I dream of still being in “La Hielera,” and wake up in a cold sweat.

As for my brother, he’s struggled since his release from detention on parole in July 2014. Since his release, he searched for pro-bono legal assistance, but most of the resources didn’t apply to him as an adult. Because he identifies as a gay man, he turned to the Los Angeles LGBTQ center in Hollywood—and began his asylum petition. In 2016, he was granted asylum, but has struggled to find steady work due to his mental health conditions. He is fearful to apply for residency, and simply can’t afford it.

Buiges believes immigration policies need to be changed.

“I think we need to go a step further and really look at some of the laws we have in place and really challenge those in the courts,” she said. She wants to see more time and independence for immigration judges, as well as a more child-appropriate process.

“We should make judges more independent in immigration courts, so that they can truly not feel the pressures of finishing cases quickly,” said Buiges. “We also need to think about how to make it a more child-appropriate process for kids.”

None of us know the exact solution to this, which is why it’s a crisis. I have hope that the current administration will give back unaccompanied minors the protections the previous administration took away. Most importantly, I hope detention can be revolutionized to make it so other kids can sleep at night knowing that their dream is within an arm's length and their painful journey has ended.