Estuardo Mazariegos, a longtime South Central community member, was returning home from work one night in early February last year when he witnessed USC’s Department of Public Safety detain a non-USC student bicyclist for riding with a broken light.

The stop happened at the boundary of DPS’ 2.5 square-mile patrolling radius around the university.

Mazariegos pulled out his phone and started livestreaming on Facebook. The footage showed DPS officers handcuff and question the bicyclist, asking if he had any outstanding warrants. When the man responded that he had a dismissed felony warrant, they told him a Los Angeles Police Department officer would be checking on him.

According to Sahra Sulaiman, who wrote about it at the time on LA Streetsblog, the incident was a prime example of a pretextual stop — when law enforcement use a minor traffic infraction to investigate other suspicions. Activists say pretextual stops disproportionately target people of color.

Mazariegos said he started filming the exchange because he sees DPS as an “occupying force” in the neighborhood that seems to have “unchecked power.”

“It just seems like the USC police are there to harass anybody that seems not to belong with or around the campus,” Mazariegos said. “I know it’s just a matter of time until I get pulled over by them.”

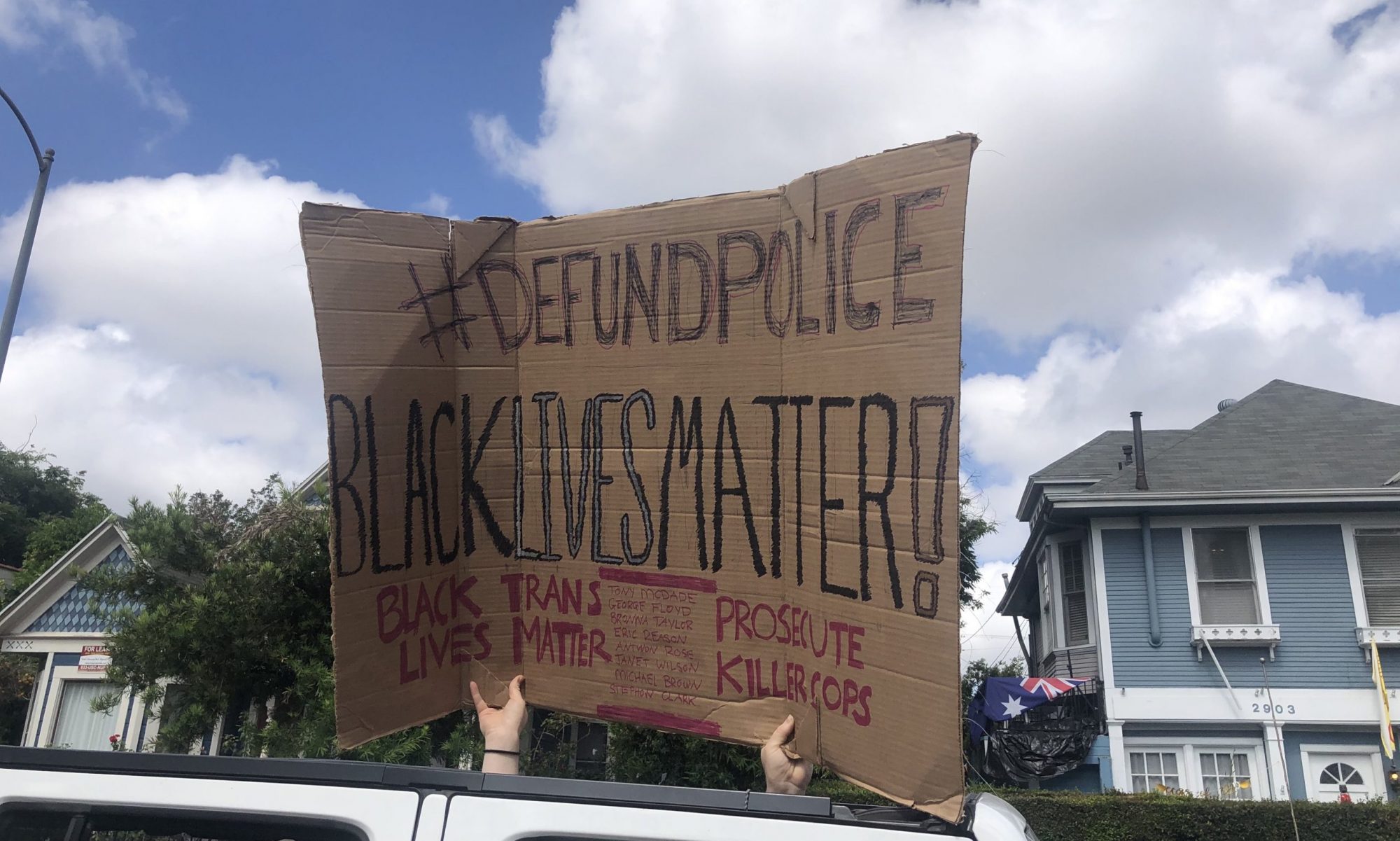

DPS Chief John Thomas admitted the officers could have handled the situation better, and said they were reprimanded. But many South Central community members, along with USC students and faculty, believe incremental reform is no longer enough. Amid the global resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, these activists want to fundamentally reimagine the notion of public safety in South Central, putting an end to what they call decades of overpolicing, by defunding DPS and redirecting that money toward the neighborhoods USC has gentrified.

Building a fortress

Sulaiman, who has been covering the community around USC for seven years, said she has traced back stories of police misconduct from both the Los Angeles Police Department and DPS for up to 30 years. But she said matters have worsened in the past decade.

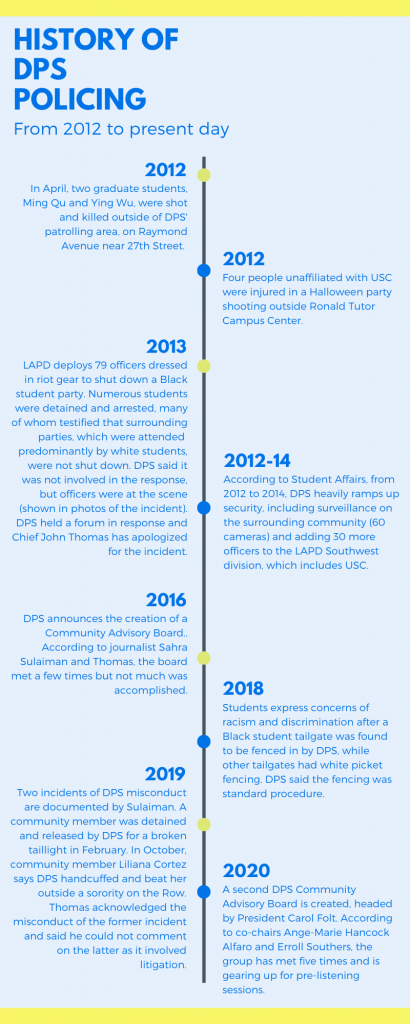

In 2012, there were two highly publicized shootings, one of which claimed the lives of two USC graduate students. Following the incidents, DPS ramped up security and policing in University Park and surrounding neighborhoods, and about 30 LAPD officers were added to the Southwest division, of which USC is a part. In 2014, USC announced it would extend coverage by neighborhood security officers, increase the number of DPS and LAPD foot patrols in the area and augment the number of cameras in the neighborhood, bringing the current total to more than 400 video or license plate recognition cameras.

But Sulaiman said the university should have done more to educate parents about South Central, instead of feeding into stereotypes about its predominantly Black and brown communities.

“Both USC and the parents were kind of implicit in that,” Sulaiman said. “This has been an issue for a long time that got intensified, because there’s so much ignorance about who the community is.”

Mazariegos said many longtime residents see USC as a “castle” and take offense that only people affiliated with USC can enter campus grounds from 9 p.m. to 6 a.m., a policy implemented by DPS in 2013.

“It’s only a matter of time until tragedy happens,” he said. “They have guns, they have batons, and they hurt people.”

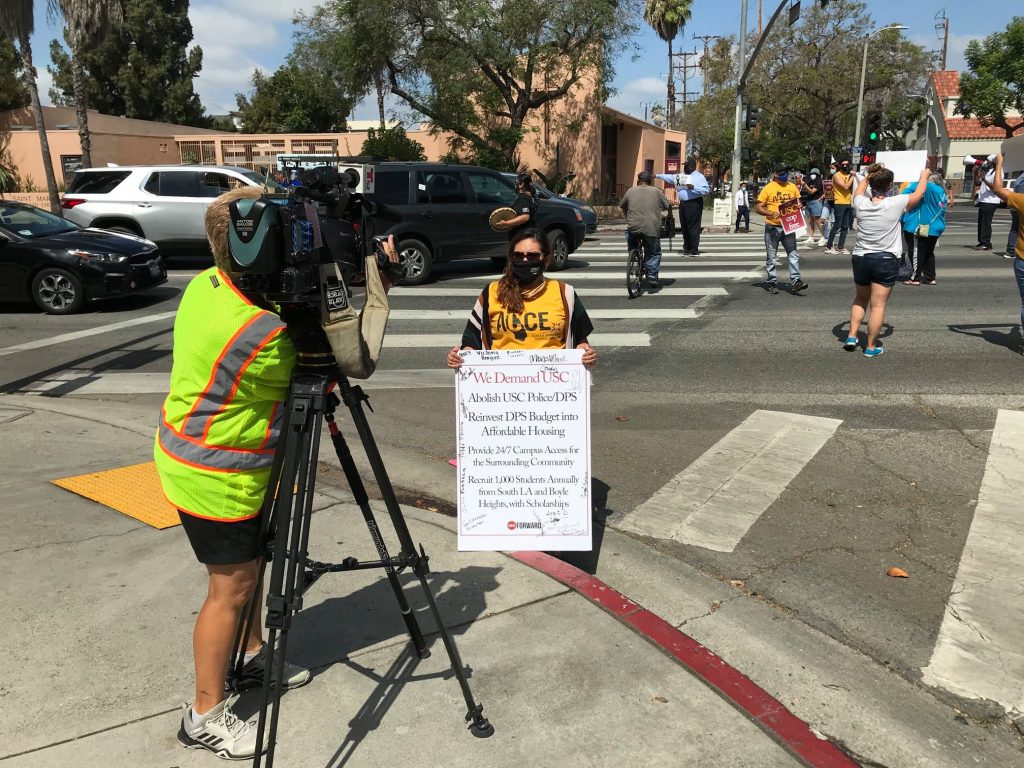

Joe Delgado, the Los Angeles director of the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment Action and a South Central community member, said many community members around USC no longer feel safe or welcome in their homes.

Delgado said all four layers of law enforcement in the University Park area, which include DPS, LAPD, USC’s private contracted security officers known as “yellow jackets” and the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, target residents of color.

“The overpolicing that happens in the community has been a problem for a long time,” Delgado said. “And it has not been addressed by USC. And that continues to be a problem for the community. So, [it’s about] taking a huge amount of money that they’re pouring into the police on campus, and using it for the community programs that are desperately needed for USC to be a better neighbor.”

The case for defunding

USC was one of the first universities in the U.S. to implement license plate recognition technology, a multi-million dollar initiative to enhance campus security measures. According to 2011 data from the U.S. Department of Justice, the university had more than twice the number of full-time and sworn officers, who have arrest powers and carry a firearm and badge, than most other universities with similar student populations. Since then, DPS has steadily grown to be one of the largest campus police forces in the country, boasting more than 350 officers, of which about 100 are armed, according to DPS Assistant Chief David Carlisle. Its 2018-19 budget was nearly $50 million, an increase of roughly $4.3 million from the year prior, when USC first began reporting its law enforcement expenditures in its annual financial reports.

Through California Penal Code section 830.7(b), DPS public safety officers are empowered with peace officer powers of arrest within their bounds of patrol. According to Carlisle, PSOs undergo the mandated 664 hours of California-required police academy training, in addition to 300 more hours required by the department. Under DPS’ memorandum of understanding with the LAPD, an agreement that dates back to the 1980s and has been renewed continually, according to Thomas, DPS officers have the right to author parking, bike and pedestrian citations. The agreement also requires DPS to report certain crimes, such as sexual assault and hate crimes, to the LAPD.

Thomas, whose tenure at DPS began 14 years ago, said that while DPS’ budget has increased throughout the years, he is not aware of the line-item budget of his department, as it is not within his jurisdiction. For students like Ochanya Ogah, Social Justice in Medicine co-president, that presents a glaring problem.

In July, Ogah and her student coalition met with Thomas and President Carol Folt to demand transparency from DPS regarding its exact expenditures. They also wanted to see documented complaints and arrest records and call logs from the last decade. SJMC pressed the university to commit to divesting $10 million each year for ten years from DPS toward increasing diversity among the cohort of medical students serving the predominantly Black and Latinx population of South Central. Folt said the university could not commit to the divestment plan.

“I think if the university really wants to show their commitment to the pain some of their students are going through right now with the racial injustices that are happening across the country, for students who want answers and want to feel safe, the university should release the budget,” Ogah said. “If you really can’t afford a divestment, if you really are only using funds that you need to protect students, there’s nothing to hide.”

Folt could not be reached for comment.

Ogah, who has been affiliated with the university since she was an undergraduate student 12 years ago, emphasized that she did not want to abolish the force, but rather consider the alternatives to policing that exist.

“There are countless stories about students who have been harassed by DPS; in my undergraduate experience, I was a student who was harassed by DPS and did not feel safe by the policing force, yet we continue to … strengthen our policing efforts, when we know that this is not necessarily the best way to spend the university’s money.”

The problem with reform

More than 20 years ago, Gould School of Law professor Jody David Armour was among the first pioneers to identify what he called “bias existing in the cognitive unconscious” — now referred to as implicit bias. He theorized that if people could recognize the unconscious bias they hold toward marginalized groups, they could actively work to overcome them.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that I was mistaken, I was sorely mistaken,” Armour said.

For Armour, who is also serving on the recently formed DPS Community Advisory Board, implicit bias training as a means of reducing racial profiling and discrimination by law enforcement is misguided.

“We’re wrong six ways from Sunday and we are wrong in ways that are harmful to members of those same stereotyped communities, because those officers are not going to be able to suddenly self-regulate their unconscious biases, just because they now know that they have them,” he said.

Instead, Armour said police officers, who he identifies as “violence workers” armed with guns, stun guns, batons and handcuffs, should not handle the majority of calls they get, which are overwhelmingly concerning nonviolent incidents. He believes the only way to reduce violence at the hands of law enforcement toward marginalized groups is to minimize contacts between them.

“We’re finally realizing that we can’t solve the problem of police misconduct, especially against members of stereotyped groups, through technological tweaks, like body cameras or through policy tweaks, like implicit bias training or de-escalation training or community policing,” Armour said. “Those fixes are … illusory fixes. They lull us into a false sense of security about having done something about the problem when we haven’t.”

Similar to other “defund the police” activists, Armour wants to redirect funds from DPS toward other services that could benefit students and the surrounding community, such as more mental health counseling and rehabilitation services for drug addiction. He believes this shift will not affect crime rates and that it is necessary to consider the comfort of individuals of color when weighing the risks of defunding. An examination of 60 years of crime data showed no correlations between police funding and crime.

In an interview, Thomas said he supported the “defund the police” movement, but contended that the slogan was a “horrible title.” He said law enforcement departments are often burdened with handling calls that should not be directed toward them, such as issues concerning homelessness, which have become criminalized as a result.

“I’m fully in support of redistributing resources away from police departments that would allow for officers to not be in a position where they’re, by default, criminalizing individuals who really need resources and support,” he said.

However, he said he wants to see more concrete solutions from “defund the police” activists, saying that he believes redirecting funds away from law enforcement without a plan in place will most detrimentally impact communities of color.

As a reporter, Sulaiman interviewed about 50 young men, ages 14 to 25, about their encounters with DPS. According to her findings, each had had a negative experience with the department and cited DPS as more aggressive than LAPD.

“LAPD can threaten them with citations, with jail — can really mess up and disrupt their lives,” Sulaiman said. “ DPS exerts their authority in other ways by handcuffing kids to their front gates, threatening to come up into their homes.” DPS lacks similar methods of accountability that exist for traditional police departments like the LAPD, according to Sulaiman.

“How, as an immigrant or a lower income resident, who has no connection to USC and doesn’t have the facility with university or the bureaucracy, or any kind of pull in any kind of way … how are you supposed to get justice?”

However, Thomas said DPS approaches policing in the surrounding community in a collaborative way, emphasizing that people living around USC appreciate and often prefer their services, such as USC’s yellow jackets program, to that of LAPD’s.

“The members of our community have become very well accustomed to seeing DPS in the area,” Thomas said. “There is built in trust from the community, a reliance upon DPS.”

According to DPS’ frequently asked questions page, complaints regarding DPS misconduct can be made at any time through any method, including phone call and email. Thomas stressed that it is DPS policy to investigate all complaints and that discrimination allegations are referred either to the department’s internal Professional Standard’s Unit or to the USC Office for Equity, Equal Opportunity, and Title IX. He also said he takes instances of racial profiling seriously and is committed to improving DPS relations with the community and students, often giving out his personal number to those who wish to discuss concerns.

The department is also currently reviewing its use of force policy and is likely to adjust its rules based on recent state law changes and evolving best practices. DPS does not permit the use of lateral vascular or other neck restraints.

DPS declined to discuss specific allegations of officer misconduct citing confidential personnel matters, according to a statement from Carlisle. The department also said it gets sued “because of the nature of [its] work.”

Reimagining public safety in colleges across the country

During the 1960s, college campuses saw a widespread increase in student-led activism at the height of the civil rights movement. As a result, higher education leaders struggled to maintain control over student demonstrations, using military and municipal police to constrain activism, according to a report published by USC’s Pullias Center for Higher Education.

Across the nation, campuses saw violent repression of student protests, from the Ethnic Studies Strikes at UC Berkeley to the deaths of four students at Kent State at the hands of the Ohio National Guard. The political climate eventually marked the birth of the “modern campus police department,” according to police scholar John J. Sloan, where institutions sought to militarize their police forces to curb unwanted student activism.

Decades later, many student activists and faculty members of color across the country are now calling on administrators to defund campus police and rethink public safety.

Led by Black student unions and groups, these organizations believe panel discussions, implicit bias training and committees are not enough to tackle the magnitude of the issue. They want to see universities galvanized into concrete action.

At Northwestern University, For Members Only, the university’s Black student union, has circulated a statement that has been signed by more than 8,000 people and student groups advocating to cut ties with the Evanston Police Department and the Chicago Police Department. Since mid-October students have marched for 33 days straight protesting for abolition. Evanston police responded by using tear gas, arresting participants and beating them.

Following the killing of George Floyd, former student body president at University of Minnesota Jael Kerandi penned a letter to administrators asking them to cut ties with the Minneapolis Police Department. Within 24 hours, UMN President Joan Gabel announced the university would no longer partner with the department for large events and specialized services. While not the victory Kerandi had hoped for, Gabel’s actions outlined a prompt, concrete response — one that many USC students and community members are still waiting for.

In July, more than 380 faculty members drafted a letter criticizing USC’s response to the testimony shared by Black students on the Instagram account @black_at_usc and Black Lives Matter movement, advocating for more robust action than listening sessions. Many faculty called on USC to redirect 25% of DPS’ budget, which is nearly two and a half times that of UCLA’s Police Department, to initiatives that will make underrepresented students and community members feel safer on campus, and to terminate its relationship with LAPD, who has killed 601 civilians since 2012, 80% of whom were Black or Latinx. These demands have echoed those of myriad student organizations.

According to the Pullias’ Center campus policing report, campus police officers are deployed in capacities beyond their law enforcement mandate, unnecessarily expose students to the criminal justice system and campus disciplinary process and negatively contribute to the campus racial climate. The U.S. stands alone in the world in its level of policing on college and university campuses.

Although research on campus policing is limited, the report outlines that three-quarters of higher education institutions in the U.S. permitted officers to carry firearms, with 94% of officers using a sidearm and chemical or pepper spray. Since 1990, more than 100 institutions have been loaned military-grade weapons from the Department of Defense 1033 program, with USC having access to LAPD SWAT officers.

The report recommends that higher education leaders create clear “upper bounds” for campus policing, such as eliminating the use of lethal weapons, limiting partnerships with external law enforcement agencies and detailing when and how campus police should be called. It also calls for creating new structures for campus safety, including using unarmed guards for daily security and focusing on restorative justice.

“Higher education leaders cannot afford to uncritically or passively maintain campus police departments within the current political climate,” the report read.

Moving forward

In 2016, following the passage of the Racial and Identity Profiling Act of 2015, the Provost’s Office created the DPS Community Advisory Board to ensure oversight and address issues of profiling. While Thomas and Sulaiman said the board met a few times, the commission did not accomplish anything of significance.

When Folt announced a second iteration of the board in July, which she would chair, many students took to social media to express skepticism at the ability of the commission to enact change, arguing that the board’s creation was a tactic by administrators to stall progress.

But Thomas said DPS oversight is of utmost importance to him and that DPS is not waiting for the board’s recommendations to be proactive, already partnering with USC schools and programs, such as the Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, to improve officer training. For Thomas, police accountability is personal, he said, as a former South Central resident and community organizer against police abuse.

“Me, not only as chief, but as a person of color, I want to make sure my experiences don’t become our students’ experiences,” he said. Thomas said in addition to CAB, DPS provides biweekly reports to the Black Student Assembly.

According to co-chairs Erroll Southers, a professor at the Sol Price School of Public Policy, and Ange-Marie Hancock Alfaro, professor of political science and gender studies, the commission is working off of, but not limited to, Folt’s five areas of focus: the role of policing and law enforcement at USC, race and identity profiling issues, DPS safety procedures, how DPS engages with neighborhood community stakeholders and how it interacts with agencies like LAPD and the Sheriff’s Department.

As co-chairs the two agree that a committee should exist in perpetuity to maintain oversight over DPS but CAB has not landed on exact conclusion of what that would look like.

“We’re building this, and we’re building it to be sustainable,” Southers said. “So we really are putting the necessary infrastructure in place: the governance, the policy, the procedural issues that have to be addressed.”

The board is broken up into four sectors, with four representatives each from faculty, community members, students and staff, as well as three at-large representatives, who hold full membership. Three board members, professors Southers, Rebecca Lonergan and Robert Saltzman, hold law enforcement backgrounds. The board also includes four ex-officio members who hold positions in the commission by virtue of their roles, such as Thomas and senior vice president and general counsel Beong-Soo Kim.

For Hancock Alfaro and Southers, being a part of the board is personal: Hancock Alfaro hails from a mixed family, with relatives who have been in law enforcement and who have previously been incarcerated. Southers, who became a police officer 40 years ago, said he constantly walks on “the razor’s edge” as a Black man in law enforcement, entering the field because of the injustices he faced as a teenager.

“It was really important for us to develop some shared trust, because it’s not clear at all that all of us agree on what the outcomes should be,” Hancock Alfaro said. “And so we are really trying to build the alternative version where we are able to civilly engage no matter whether we’re coming from one perspective about how much funding police should get or another.”

Lennon Wesley III, a USG senator serving on the board as one of two undergraduate student representatives, said he is “cautiously optimistic” that now is the right time for the board’s creation and that it will not skirt its responsibilities.

“The importance that’s been placed on the focus on actually getting the work done has … abated my fears a little bit,” Wesley said.

Since Sept. 18, the board has convened for five two-hour-long meetings, where members have discussed their mission and priorities, received an overview presentation from Thomas about DPS and discussed the implementation of listening sessions for the spring semester. To shape and design these sessions, CAB will pilot smaller conversations for two weeks in November.

According to Southers, the commission has not taken a deep dive into DPS operations, such as onboarding, hiring and budget. However, the co-chairs said they are committed to transparency and that CAB will soon launch a website, along with a social media account, to detail meeting summaries and facilitate conversation and insight.

Wesley, Armour and the co-chairs said they felt hopeful about what the board may accomplish and praised Folt for her leadership. Armour noted that the board’s effectiveness will rest on how responsive administration will be to its recommendations, as well as how focused the board members will be in committing to tangible change.

“I hope that we can live up to the expectations of those who are critical and skeptical,” Armour said. “And if we can’t, I hope our feet are held to the fire, I hope that we’re held accountable.”