It’s 7:30 p.m. when Vincent Montalvo picks up his cell phone to answer missed calls.

Since 8:00 a.m., as he has for the past two decades, Montalvo starts his day to the sound of his phone buzzing, residents of Los Angeles calling for help, waiting for answers to their livelihood.

Eviction protection, land use, housing insecurity, environmental hazards, gentrification: Montalvo knows all the issues as the neighborhood councilman for the city of Lincoln Heights. By 10:00 a.m., he has answered almost 10 calls. Families need letters to be written, rights to be protected, and lives to be saved.

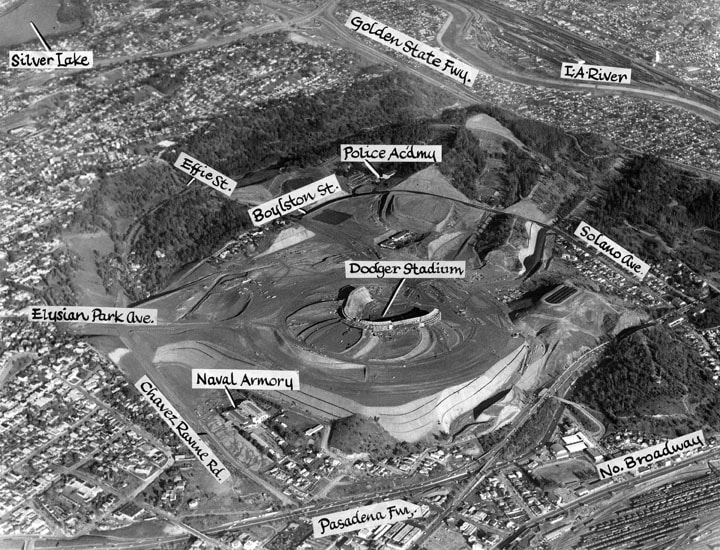

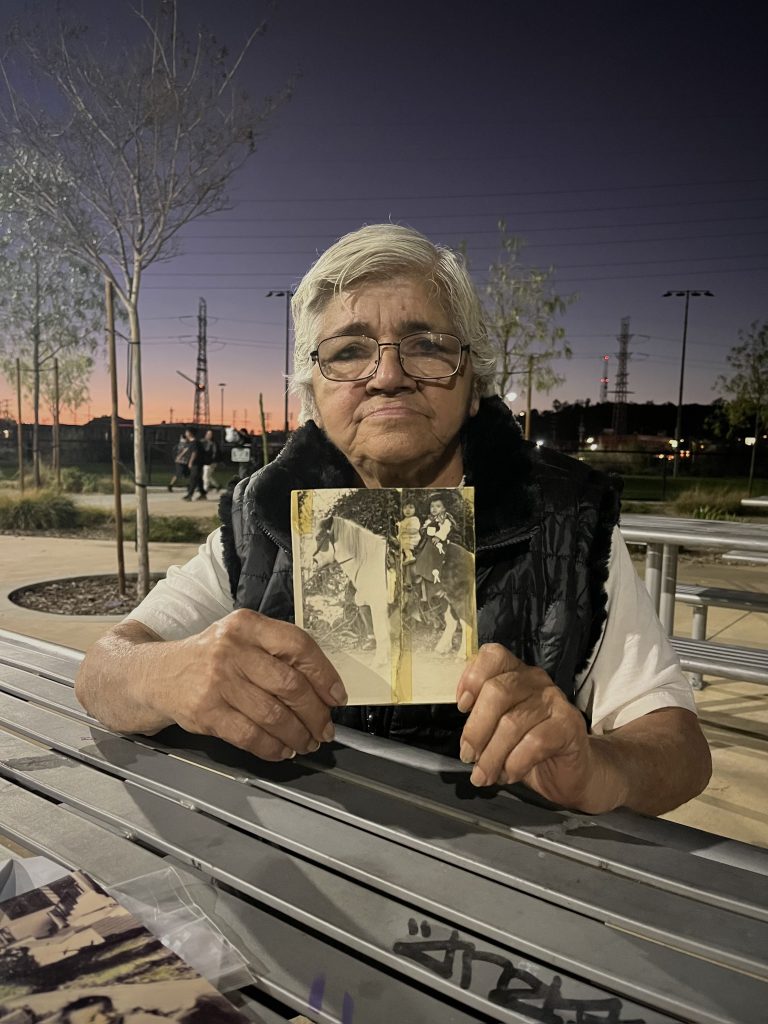

Montalvo credits his lifework to his grandmother, Adela De Nava, who more than 60 years ago watched as the city of Los Angeles planted police cars and bulldozers in her barrio to raze an entire community to make way for what would become Dodger Stadium. The pain carried by those who once lived in the area now commonly referred to as Chavez Ravine has been passed on through generations.

Never again.

That’s the mantra De Nava, now 85 years old, and her grandson live by.

Call by call, Montalvo seeks solace in maintaining community in an era when few know their neighbors by name.

Montalvo writes at his small desk inside his bedroom in his shared family living space on Avenue 18 in Lincoln Heights. His mom, dad, and younger brother live under the same roof. The small space isn’t that glamorous, but for him, it gets the job done. What fills the walls of his bedroom are the thoughts he speaks out loud. Ideas like how do we protect the city, our people, the most vulnerable? What outdated city laws continue to oppress the rights and livelihoods of the poor?

“Democracy is indigenous by right,” Montalvo yells into the phone, explaining how indigenous contributions play into our own political systems — discussing and creating tribal laws by chiefs and leaders of native tribes parallel modern-day senate and council meetings according to Montalvo. But the policies supported by city officials that create rent control and housing laws enacted into the City of Los Angeles, he finds, to continuously harm those he works to protect most, Black and Brown folks who come to him day after day, in search of hope.

By 12:00 p.m. Montalvo has answered 25 calls.

Just six cement stair-steps down from his front door and a slight left turn over the shoulder, Dodger Stadium’s palm trees peek through the neighborhood trees — what would consist of a half-hour walk to his grandmother’s past life.

“I only do this because it’s part of my identity. My grandma can tell you her story,” Montalvo says. “She is why I do what I do, why I love what I do.”

Less than a 15-minute drive away, seven and a half miles north of Montalvo’s home in Lincoln Heights, De Nava lays next to her husband, John, as he fights recurring, unexpected illnesses. First a cold, then pneumonia, then a hospital visit or two, and then back to their home of over 25 years. De Nava suspects it could be old age; he is 95.

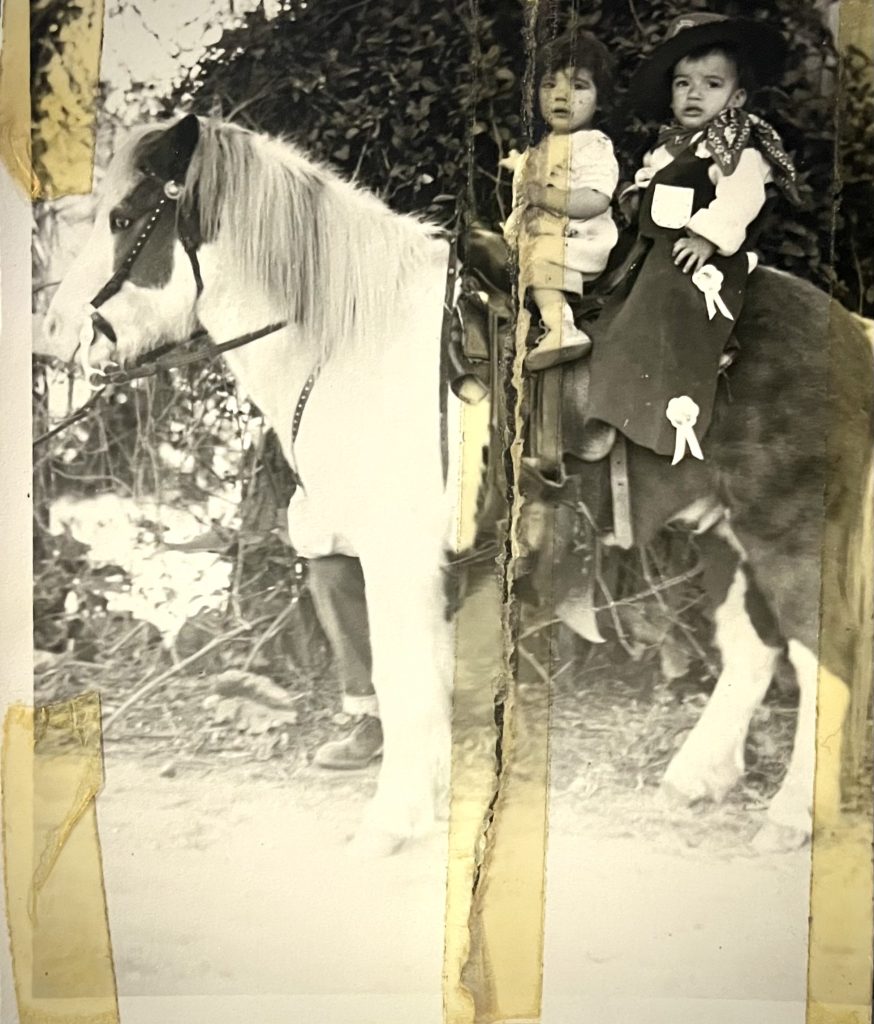

She takes care of her husband, her home, her cat named Papi, and her memories of Palo Verde. She brings up her childhood constantly, asking her husband if he remembers the white donkey that accompanied the neighborhood fruit man. Her white, combed-back hair makes space for her blue eyes and light skin to glisten, a voice that catches anyone’s attention, and a sharp attitude that, in her words, is quick to call “bullshit.”

De Nava describes her upbringing as beautiful, full of community, love, family, friends, music, kids, and pure bliss. “It was like a fairy tale; there was nothing like Palo Verde. There will never be anything like it ever again.”

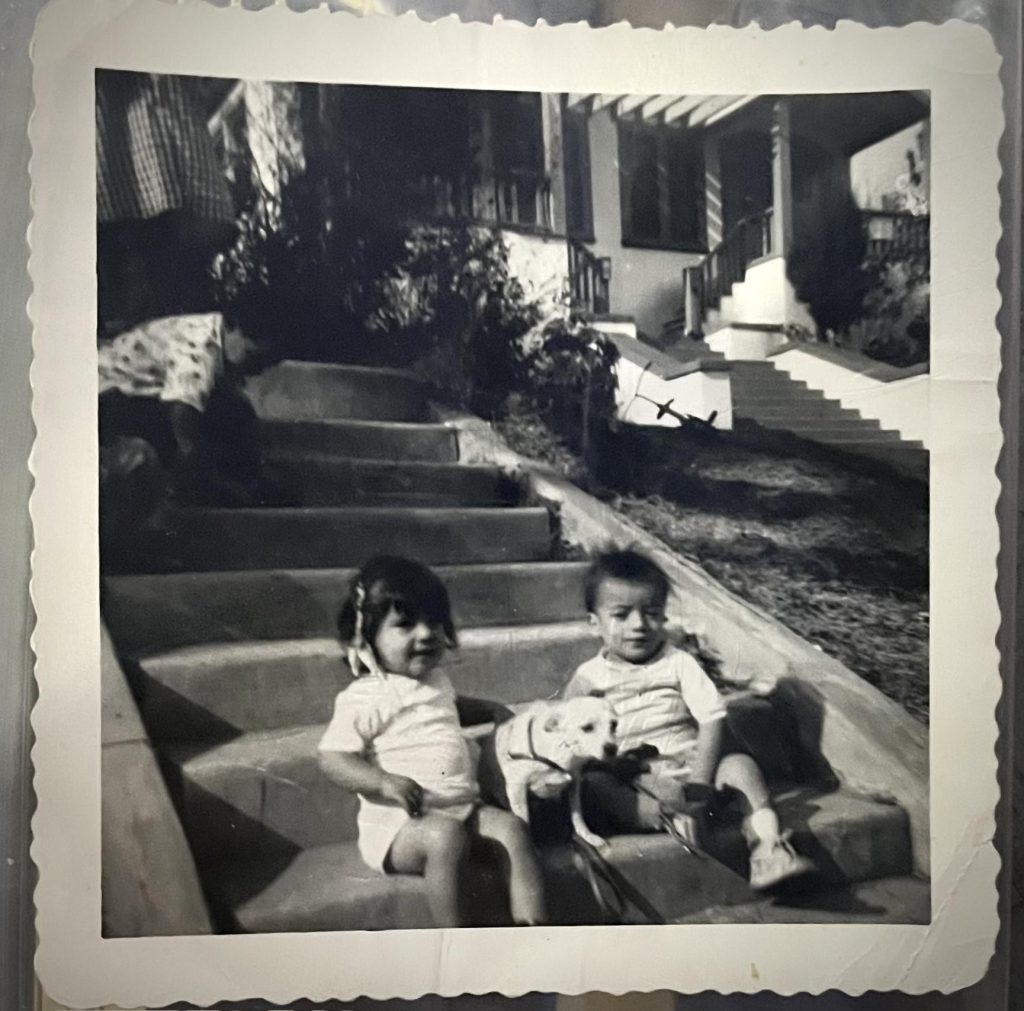

In 1959, at just 23 years old, De Nava — along with her husband, mother, father, and eight-year-old twin children — were forced to leave their home at the top of their barrio, Palo Verde. Their beloved community would no longer be their oasis, their safe haven, their home.

“What can you do when people have more power than you?”

Adela De Nava on being evicted from her Palo Verde home in 1959

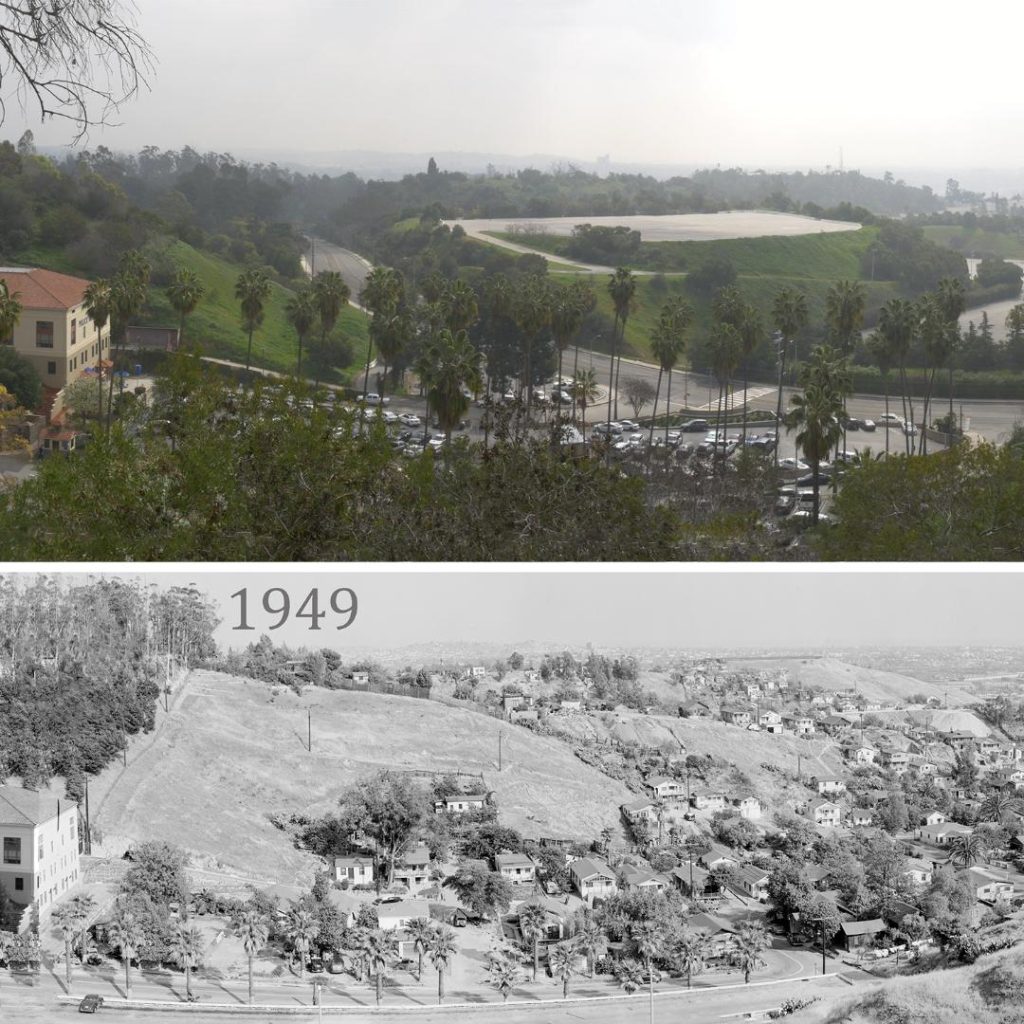

The De Navas and nearly 1,100 other families were pushed out of their homes as Los Angeles welcomed the construction of more than 300 acres over the land of Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop communities. Today, it is Dodger Stadium.

“It wasn’t just Mexicans in the barrio. We had Russian neighbors and Black neighbors too, and they all spoke Spanish because of us, the Mexicanos,” said De Nava. She paused mid-thought, lowered her shoulders, and shook her head slowly. “What can you do when people have more power than you?”

The trauma of her past haunts her. If she receives a bill in the mail, De Nava turns to her checkbook at arms reach, and pays the bill without hesitation. She despises the feeling of owing anyone anything, whether it’s a check, food, apologies, or the apartment she’s rented for over 25 years. Paying her bills is how she finds stability, a way to protect against anything being taken from her ever again.

The Palo Verde community of Los Angeles, along with La Loma and Bishop communities, comprised what is known to Angelinos today as Chavez Ravine.

“I don’t get why they call it that today,” De Nava says. “From what I remember, Chavez Ravine was on the other side of the [LA] River. We were never that; we were Palo Verde.”

Remembering her home address, 1776 Reposa St., De Nava still has trouble fighting back her anger.

Looking over at her husband John, whose breathing is supported by an oxygen aid for the majority of his days, she knows his stories still live deeply in his heart as much as in hers.

“Living in Palo Verde was freedom. It’s a freedom where you could do what you wanted to do,” he chimes in. In the hills, he’d fly his kites and ride his skateboard through the sunset. Adela could be found at the baseball field between the ridges of another hill, known as “lefty” for her good arm.

In between his left-hand thumb and index finger, “P.V.” is inked into his brown skin — for Palo Verde.

The communities that comprised today’s Chavez Ravine were developed in the 1840s by Julian Chavez, the first recorded landowner. Beginning in the 1900s, Mexican American communities began to populate the region. The three neighborhoods formed on the ridges between the neighboring ravines. There was a local grocery store, a local church, and Palo Verde Elementary School.

“All the barrio was family, a big family, a happy family…everyone knew everybody,” De Nava says. She remembers times of joy — birthdays and baptisms, graduations, and Christmas. Because everyone didn’t fit in a single home, “We’d all be at the park to celebrate, the comadres and compadres, everyone was there, a dream.”

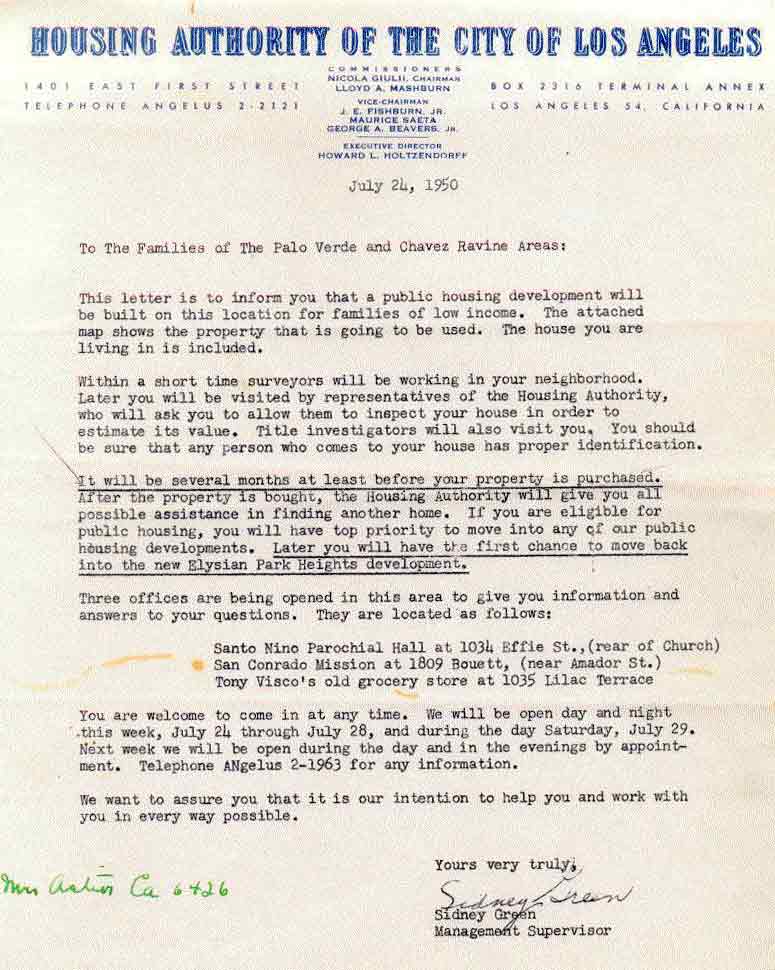

What hurts De Nava the most is her naivety at the time. There was no understanding of the term eminent domain, which refers to the power of the government to take private property and convert it into public use. She instead remembers the six white men scoping around her barrio.

“Quien va ahi?” the mothers at home would ask. Everyone was too scared to ask the group of men directly.

The men would point at the homes, scouting for land, making promises of a new neighborhood of new apartments, complete with a bigger park, a pool, and a new way of life. That promise was not kept for long

The Fifth Amendment provides that the government may only exercise the power of eminent domain if it provides just compensation to the property owners.

For De Nava, the money never added up. She says her family, along with the remaining families in Palo Verde, were given checks below their house value. City government officials providing these checks would visit the local hospital first, add up the amount of money residents owed to the hospital based on their various doctors and emergency visits, and take that balance out of the total check for their home values.

According to Montalvo, these archival housing documents are “being destroyed” at the C. Erwin Piper Technical Center in Los Angeles after he asked to retrieve them for family purposes.

To this day, it infuriates De Nava and her husband. All of the freedom they could ask for was theirs, until it wasn’t.

Palo Verde Elementary School, Palo Verde Cemetery, and the hundreds of neighborhood homes were buried and bulldozed. According to John, the graveyard headstones were removed, but bodies remain under the 110 freeway. The elementary school’s roof was taken off, and the building was filled with dirt to even out the hillside.

For De Nava’s eldest daughter, Adela Montalvo, her memories from eight years old have stuck in the back of her mind since 1957.

“I heard mom say that we’re going to have to move, that we’re not going to be able to stay here. That’s the only place we knew as home,” says Adela. “[The kids] would sit around and talk about, ‘What are we going to do with our dogs, our cats, the cows, the goats, the chickens?’ We understood what was going on.”

When she gets the chance to pass by Dodger Stadium, the tears in her eyes flow unapologetically.

Montalvo makes it a point to call his grandparents every other week, checking in on their health, food supply, and living conditions.

In 2021, De Neva noticed her senior living community, Reflections at Yosemite, struggling to pay for their housing every month. The troubling conversations among her neighbors made her think of calling her grandson for his advice. It also reminded her that nobody deserves to have their home taken away from them.

De Nava and Montalvo helped introduce Section 8, the Housing Choice Voucher Program, into her senior living community. For De Nava, it was a way to spread her grandson’s knowledge and the guidance she wishes she had back in 1959 and in the decades that followed.

“Home is community and community is home,” says Montalvo. Today, he sees himself as the caretaker of his grandparents’ stories.

He visits community colleges across California to speak on behalf of his grandparents and is the co-founder of Buried Under the Blue, a nonprofit organization made up of direct, living family descendants of residents of Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop working to preserve its history. He partners with professors in Mexico City, cross-examining his indigenous roots, the indigenous practices used in Palo Verde through the sobadores and curanderos — naturalistic massagers and healers — the musica, and their native Nahuatl tongue. To Montalvo, these stories never end regardless of being buried under stadium lights, palm trees perforating the historic ballpark, and Dodger blue.

On a wooden coffee table placed against the wall of her cat-caricatured, snug living room, De Nava keeps an 11 x 14 black and white photograph of her barrio. Pictured are eight children making their way through a back entrance of Palo Verde Elementary School, two of them jumping, playing in the sunshine that only an Angelino can recognize. Behind it, perched on the hill are 14 homes, hiding behind agaves, camphor trees, and nopalitos. They sit in neat condition, with stable roofs and solid foundations. The roads make way for the families to visit each other with open arms, comadres y compadres — godmothers and godfathers — watching out for each other, the children, the pachucos, and the barrio they love.

“If only I had a time machine,” she says. She’d transport herself back to the barrio to play among the hundreds of children. Just one last time.