Playthings

by Rabindranath Tagore

CHILD, how happy you are sitting in the dust, playing with a broken twig all the morning.

I smile at your play with that little bit of a broken twig.

I am busy with my accounts, adding up figures by the hour.

Perhaps you glance at me and think, "What a stupid game to spoil your morning with!"

Child, I have forgotten the art of being absorbed in sticks and mud-pies.

I seek out costly playthings, and gather lumps of gold and silver.

With whatever you find you create your glad games, I spend both my time and my strength over things I never can obtain.

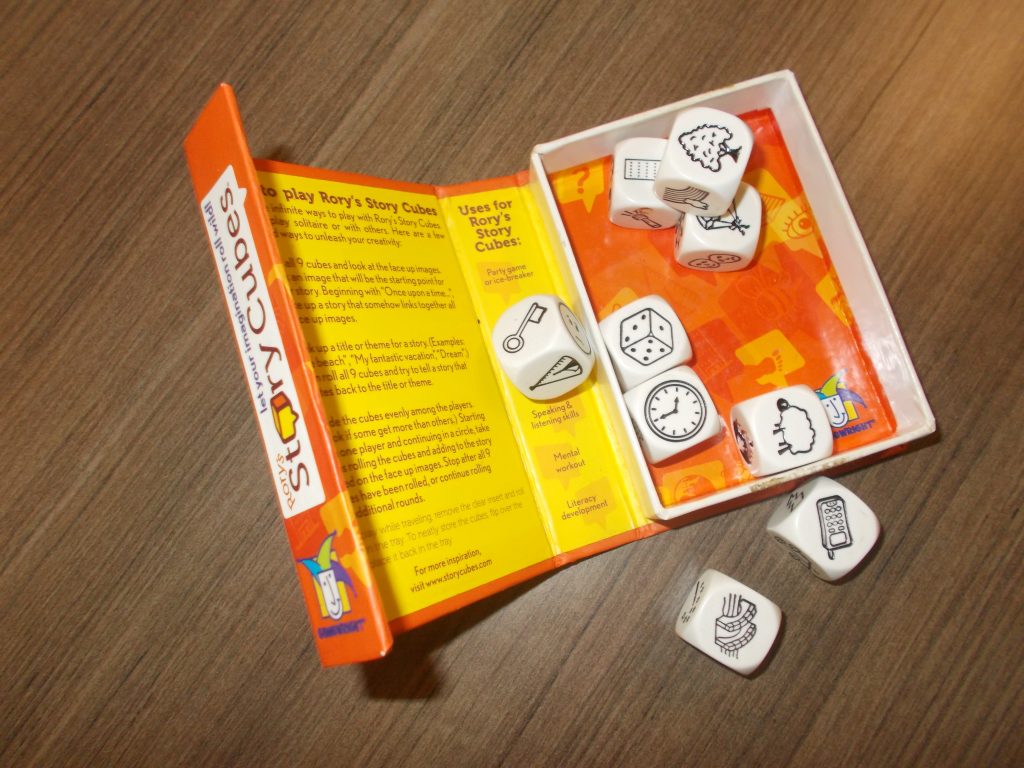

In my frail canoe I struggle to cross the sea of desire, and forget that I too am playing a game.One of my childhood birthday presents, Rory’s Story Cubes – a dice game for infinite stories.

Most everyone in the world is tied together by this one fundamental experience of childhood, shared beyond borders and across ages – most of us grew up playing pretend or make-believe.

Whether it might have been inventing an imaginary friend, running simulations of a tea party or a soft toy vet visit with plastic tea cups and miniature stethoscopes, creating fantasy scenarios of heroes and villains, or making up a dreamland with mythical creatures, we were privy to participation in this whimsy that was our ability to role-play and tell a story.

A child’s world of imagination is not hindered by a lack of access to material things, and takes inspiration from any available props at home or in nature, as outlined by poet Rabindranath Tagore in Playthings, 1913. It has been well-documented as a tool to help children develop social, language, interpersonal and problem solving skills.

There are some of us who take this spirit of whimsy and imaginative strengths of storytelling into our school years through activities like fiction writing, acting, or even babysitting. There are fewer who pursue majors in the creative arts, and subsequently even fewer who seek careers in fields like screenwriting and theatre.

And so, sadly, a lot of us lose touch with our innate abilities of world-building, role-playing and creativity. The art of storytelling, a concept so fundamental to the existence of human culture it is difficult to know who we were before our stories, may be dying out.

We are headed into a world that is now increasingly turning to artificial intelligence to create profile pictures on social media accounts where we present a highly curated version of ourselves, which could mean that we are losing our ability to be true to each other, even when we share personal stories (Instagram or otherwise).

My love for storytelling is what led me to pursue journalism as a major when in university in the first place. I love talking to people about their interests, and connecting with them over the universality of human experiences. I believe telling each other stories, and then telling each others’ stories, is how we build relationships in life and grow more empathetic to different lived experiences.

So when I stumbled upon the idea of table-top role-playing games (TTRPG’s) through Dropout’s Dimension 20, I was excited – here was a group of adult creative storytellers, coming together to build a fictional world, inhabit it as characters they create, and role-play to weave together a story rich in both backstory and developing obstacles, over more than 20 hours of play sessions.

There are many versions of TTRPGs, Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) being one of them. Most of them utilize dice as a form of randomization to determine player outcomes and are run by someone called a Game Master (Dungeon Master in D&D), who narrates, moderates and regulates play.

To understand the mechanics of how a TTRPG works, it is best to go through an example game. Let’s say we’re playing a modern fantasy campaign set in an otherwise normal high school full of fae, werewolves, witches and more. The players could encounter their first obstacle in the form of a math test. Each player suggests an action their playable character (PC) takes, such as staying up all night using magic potions and studying hard, or transforming into a werewolf due to the full moon and destroying the test papers, etc. The Game Master then decides how difficult this course of action will be, and this is where the dice come into play.

Dice in TTRPGs typically range from pyramid-shaped 4 sided dice to icosahedron-shaped 20 sided dice, with d6, d8, d10 and d12 along the way. The d20 is the most used dice for play due to its maximum variation, and the rest are used for secondary actions like healing post battles.

The GM may decide that the werewolf PC has a high likelihood of getting caught and could set their difficult check or DC at a higher number than that of the PC who took magic potions to pull an all-nighter. If the player rolls a number higher than the DC, then they would be successful in their action and get to dictate the play, telling us how they destroyed the test papers as a werewolf, otherwise the GM resumes control of the narrative and lets the player know their fate.

Now while those who play on Dimension 20 are more often than not actors, improvisational performers, writers, artists or otherwise, generally those who play TTRPG’s in real life come from all walks of life. The mechanics of the games easily lend themselves to learning settings and have been found to better scholastic and communication skills.

Recently, researcher Orla Walsh from Ireland’s University Cork College published a study in the International Journal of Role-Playing about the impact of Dungeons & Dragons on mental health. I examined the paper’s key themes by talking with players from varying experience levels, as well as creative and non-creative careers, to understand more about how we could utilize TTRPGs as a way to get better at storytelling and better renew our human connections again.