The first things that come to mind when envisioning psychological therapy is a leather lounge couch, towering bookshelves lining the walls as if they were there to protect the security of your conversations, and most importantly, the inquisitive and empathetic therapist with his or her notepad, pen and glasses, staring back at you from across the room.

Now, what happens to this image when you add six feet?

Six feet is the least of it, really. Imagine all of these external, spatial, and human-centered factors are eliminated and replaced solely with a computer video camera – a completely virtual therapy experience known as “teletherapy.”

This is the new normal, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its subsequent social distancing restrictions leading therapist’s offices to shut down nationwide. This shift created a domino effect, sending shock waves throughout the entire psychological healthcare industry, creating change for licensed professionals and their patients alike.

Steven Scrivo, a 30 year old licensed professional counselor in the state of New Jersey, moved his entire private practice online at the beginning of the lockdowns to continue meeting with patients: “I was just starting out as a therapist, so I was subleasing from an office in Montclair, New Jersey, and then all of a sudden I was working from home one hundred percent of the time. I moved all of them [patients] to Zoom. It was all totally new.”

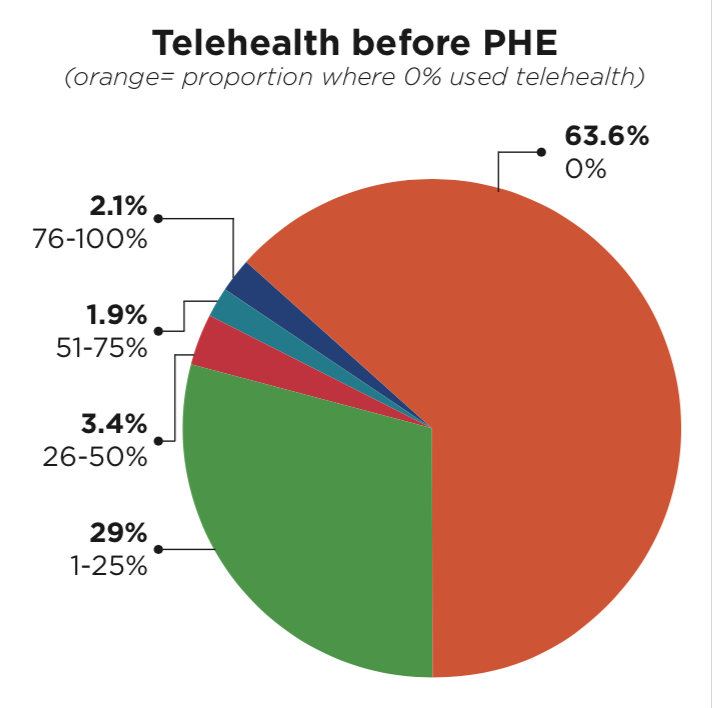

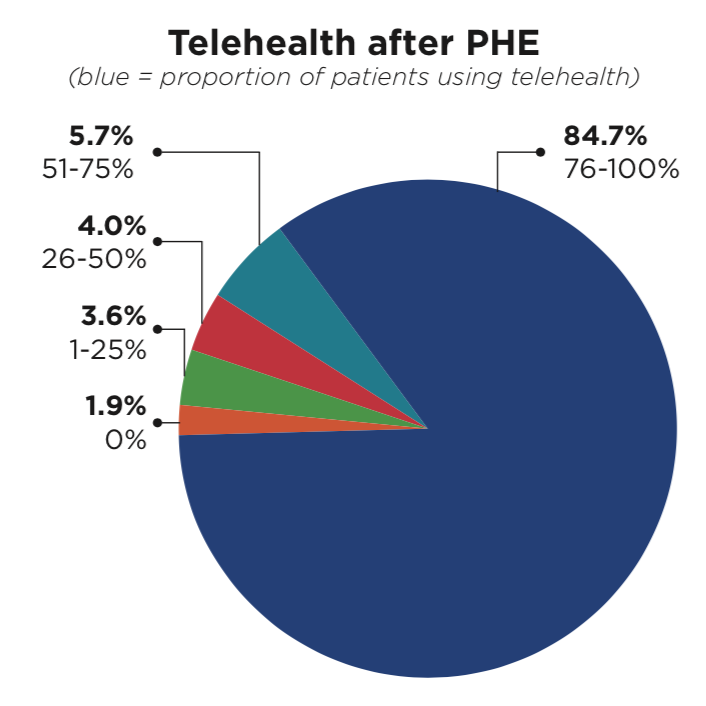

If people were not accustomed to virtual therapy before, they certainly were after the onset of the pandemic. In May 2020, the American Psychiatric Association conducted a telehealth survey sampling 500 of its members to study the frequency of in-person versus virtual sessions and compare the rates from before the public health emergency to after.

Results show that before COVID-19, 63.6% of the psychiatrists responded seeing zero percent of their patients via telehealth and only 2.1% used telehealth 76-100% of the time. Just a few months later once the pandemic hit, the number of psychiatrists participating in teletherapy the majority of the time jumped to 84.7%, leaving a mere 1.9% of respondents still not attending online sessions at all.

Adapting to this new way of life hasn’t been easy for some patients. Beatrix Thomas, a 21 year old college student from San Diego has been going to therapy for over five years now.

“The transition from going to her office and having a safe place where I can talk about my problems and then leave, leave those issues there, into opening up my laptop like I do for school, like I do for talking with my friends, and just sitting in my room and then what? I turn off my computer and I’m still there, stuck with my thoughts and I feel like I’m alone again… that was a really hard transition for me,” said Thomas.

Although telehealth can be extremely challenging, there are perks. Scrivo said, “everyone can admit that it’s easier to take out a commute to an office, it’s easier that you may not have to change an outfit, you know to get very personal, or you may be able to work from a different place.” He said it’s “undeniable” that telehealth gives his life convenience.

How Telehealth is Breaking Down Barriers to Accessible Mental Healthcare

Although there are benefits and drawbacks to a teletherapy experience, finding success in a new frontier was not guaranteed; in fact, once the pandemic officially settled in, it was widely considered to be too transitional of a time to take even a minor professional risk. Any business changes made in the first months of 2020 may have appeared solid, but as is obvious in hindsight, were subject to especially severe pandemic circumstances.

Brandon Shindo, a licensed clinical social worker in California, took a big career step in the early months of 2020 and decided to join forces with his partner to start their own group practice dedicated to servicing young professionals and minorities. Unbeknownst to them, the pandemic was about to hit.

However, theirs is not a story of crushed dreams; rather, Shindo calls coronavirus a “blessing in disguise,” crediting it for helping him expand his network.

“Prior to the pandemic what we were doing was we were servicing mainly LA County… what we realized was we weren’t quite getting the population that we hoped for and part of that was just logistics…With telehealth, the majority of my caseload is up from the Bay Area, in San Francisco, and in San Diego; 25% are here in LA County.”

Brandon Shindo

While the widespread use of telehealth is fairly recent, the demand for therapy to be more convenient and accessible has been talked about in the community for a much longer time. The Mental Health America’s 2020 Access to Care Survey states that 22.3% of all adults with a mental illness reported that they were not able to receive the treatment they needed – a statistic that hasn’t declined since 2011. The survey also reports that as of 2021, 64.8% of adults living in California with a mental illness received no treatment whatsoever.

“Individuals seeking treatment but still not receiving needed services face the same barriers that contribute to the number of individuals not receiving treatment: no insurance or limited coverage of services; shortfall in psychiatrists, and an overall undersized mental health workforce; lack of available treatment types (inpatient treatment, individual therapy, intensive community services); disconnect between primary care systems and behavioral health systems; insufficient finances to cover costs – including, copays, uncovered treatment types, or when providers do not take insurance,” the survey states.

Telehealth presents an alternative for people who feel let down by the traditional institutions of healthcare management, where there is a lack of general accessibility due to socioeconomic (SES) factors including but not limited to age, education, income, distress level and family structure.

Thanks to the internet, it’s become more possible for these people to access free resources online. However, free resources online do not equate to having a therapist with a personalized plan just for you. Noticing there was a market for digital yet still intimate therapist-patient relationships, clinicians took to the web to begin fostering those connections. It was not until the pandemic, though, that most therapists had a strong reason to transfer their practice to a digital setting.

Could Social Media (Actually) be Good for your Mental Health?

This new phenomenon in the clinical psychology world, like many other things in our daily life now, involves social media: many therapists, like Shindo, have chosen to rise to the new digital challenge at hand by creating their own platforms on social media and breaking into the world of mental health-oriented content creation.

“Time is the greatest gift you can give to a person and if you give them your time or even just have them read your post, it creates this relationship on an indirect or direct level. Content creation for me is therapeutic in a way and I enjoy doing it, but it also allows me to break that stereotype of what a therapist does. Sometimes people think therapists are very straightlaced and have this perfect life and I really aim to show that I’m not perfect… I want people to feel like I’m relatable and social media allows me to do that,” said Shindo.

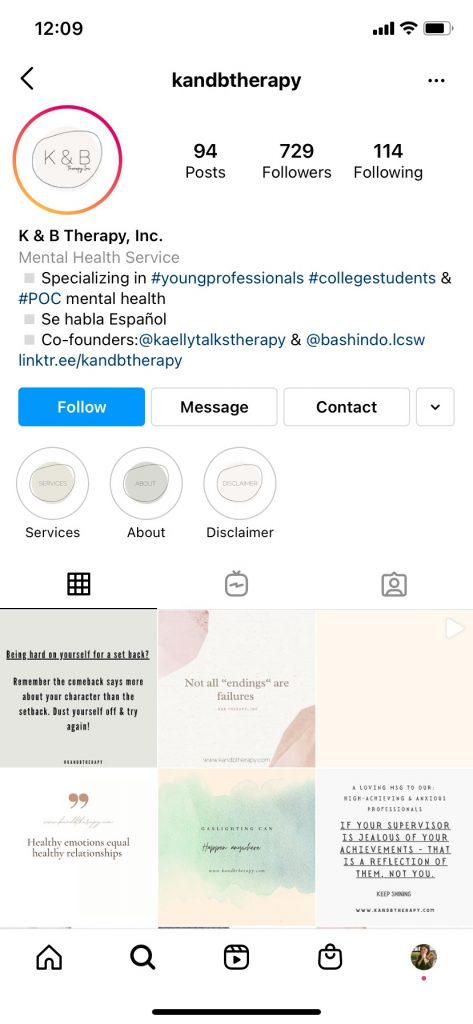

Shindo runs his own personal account, @bashindo.lcsw, as well as the representative Instagram of the group practice that he and his partner own, @kandbtherapy. These accounts are run across multiple platforms, with the largest followings on Instagram first, and then TikTok with a slightly smaller follower count, being that it’s one of the newest social platforms and has only gained immense popularity since the start of the pandemic. He operates a Facebook page as well. He began using the handle @bashindo.lcsw in the Fall of 2017, when he noticed how social media can be powered for good and stimulate healthy conversation around mental health. He has garnered about 2k followers since he began developing his social media presence.

Shindo’s Instagram bio tells you about himself; he’s an entrepreneur, a Japanese-American/Asian American therapist, Coach and Keynote Speaker, a cofounder of K & B Therapy, Inc. – @kandbtherapy – based in California.

He follows standard Instagram practice that focuses on aesthetics: having a theme throughout his colors, visuals and frequent posts, and utilizing the many features the app offers like feed posts, hashtags in captions to increase engagement, stories that survive for a 24-hour period and allow for aggregation and reposting from other accounts, highlights on the homepage where stories can be categorized and live forever, and IGTVs which allow for longer form video and live streaming. These long-form videos involve Shindo in front of the camera where he speaks about his own journey, what private practice entails, finding a therapist, and relatable anecdotes with thematic messages of self-help. His feed is filled with self-quotes, quotes by others he finds personally inspiring, and information on how to further connect with him for a real session of teletherapy.

When Shindo started his account in 2017, not every therapist was breaking into the world of social media, and not everyone believed it was a good thing. In fact, in that same year, one study conducted in England by the Royal Society for Public Health determined that Instagram was the “worst social media platform when it comes to its impact on young people’s mental health.”

Another survey produced by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that year proved that levels of mental illness in young people are rising. The 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health revealed that from 2008 to 2017, serious psychological distress – including general anxiety and feelings of hopelessness – among 18 to 25 year olds surged by 71 %.

Why the drastic jump? Over that decade, society experienced a major shift with the introduction of the smart phone and social media, affecting every one but especially impressionable young people. The evidence – seen societally and statistically – created a widespread belief that social media was the enemy of mental health.

When Thomas began experiencing mental health issues, she attributed her low self esteem to what she saw on social media.

“I was in a really low point in my life,” she said, as she thought back to her junior year of high school, the year she started seeking professional help. While going to therapy alleviated some things, Thomas wanted more than just a weekly session. What she wanted was to “change the narrative” of what she saw on her Instagram feed.

So, she went looking for something new, ended up online and found accounts like @ofkin, @ruokday and @beamingdesign – all of which post daily affirmations and small yet impactful positive reminders.

“I really needed something different, and oh my God, I found it. It was the most exciting thing for me,” she recounted.

A few years later, social media boasts thousands of accounts similar to these as well as other mental health based accounts operated by licensed therapists like Shindo, which makes for a wide network of diverse content appealing to every type of person.

In today’s world, we also have TikTok, a social media that’s taken a complete cultural hold over society in just the last year. The video app is coming under similar scrutiny as people are wondering just how psychologically detrimental it can be. Because it is so new, there are no legitimate studies or research on the app’s impact on mental health. It will take time to see if any data surfaces that support the claim that TikTok causes mental health problems.

So, Is your Shrink the Next Big Influencer?

Not necessarily.

There are such polarizing views on the effects of social media on mental health; people tend to see it as total good or total evil. Scrivo and Shindo, both men in their 30s, consider themselves in the millennial population, a group that reports almost 100% daily social media usage as of 2019. Shindo is a huge proponent of therapists creating content; and Scrivo is not at all – and said he never will be.

Scrivo has nothing against content creators, but simply prefers to keep his social media life separate from his professional life. “The reason why I didn’t do it is because they [the accounts] are very general and when I’m speaking with a client, it’s very specific to them,” he said. He mainly works with young adults who have trauma in their backgrounds, and who all typically have had a unique experience that caused their life to go array. These topics can be hard to tackle in one square box on Instagram or a video capped at 60 seconds on TikTok.

Shindo defended this perceived notion that content is too basic or vague because he – like many other creators – showcase their specialty and target their intended client base through the messages on their platforms. For instance, much of his recent content revolves around the struggles of the Asian American community, most notably the spike in anti-Asian race crimes since the pandemic began. Shindo makes sure his content relates to the real and current issues this population is facing to not only empathize, but stand out.

Both men, however, agree that social media accounts do not replace professional and customized therapy.

Shindo, who believes accounts like his are great for self-help, can only do so much. “You need to set those boundaries for yourself and recognize when it’s becoming overwhelming, talk to a professional,” he said.

“A real counseling experience is where it’s at when it comes down to the real work getting done.”

Steven Scrivo

Thomas said she will certainly return to in-person therapy when her therapist transitions back and state guidelines permit it. In the meantime, she is doing her best with virtual therapy and looks toward social media accounts for glimmers of positivity in what’s been a very dark time for many.

“I am one of the biggest advocates for mental health awareness on social media, because I suffered so much and when I was looking for help, it wasn’t something that was really out there or easy to talk about,” she said.

How are our Future Therapists Adapting?

This era of digital acceleration and the new age of therapeutic content creation has had trickle down effects in the psychology field all the way to PhD students, who are studying and training to become licensed professionals.

Crystal Wang, a 27 year old from the Sacramento area, is currently in her 5th year of the clinical science clinical psychology PhD program at USC where she is a doctoral candidate and approaching her graduation.

In her first few years in the program, she and her peers “didn’t receive any [digital] training whatsoever,” which she attributes to the older age of her professors. She said the majority of efforts to learn digital training once the program was rocked with COVID-19 effects were student-driven.

“I really had to push the faculty to find me telehealth experiences to get the minimum required hours to apply to internship, but it [telehealth] was a huge struggle for our program, trying to find the tech-based way of making that all possible.”

Crystal Wang

The students in the program could not see any patients for months; not until they eventually figured out an intensive protocol for telehealth that was HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) compliant, meeting intense requirements for patient confidentiality.

Despite the initial chaos and what Wang called an “extended transitional period,” they have figured it out now and even seen positive outcomes. She described her experience in the Interprofessional Geriatric Curriculum at Keck, where she was partnered with a mandarin speaking senior citizen to have conversations together. Prior to the pandemic, her patient was reluctant to attend meetings at all in the Downtown L.A. location, but now, she constantly texts Wang using the Chinese messaging app WeChat and she never misses a session.

“In the next ten years, there will be a lot of virtual and app-based therapy. I want to make it clear that although this is helpful, I really do think that for more severe cases, being in person face-to-face is the best solution,” said Wang.

Wang’s biggest takeaway from this whole virtual experience and the digital journey ahead of her as she enters her career is how paramount it is to maintain ethics in the psychological healthcare industry.

“Marketing your practice on social media has ethical implications, too. I am cautious because people can take these tips and run with them… I’m worried about liability issues,” she said.

Wang agrees with Scrivo and Shindo, her professional predecessors, in reaffirming that tailored interventions are best practice for diagnosing and solving mental health illnesses and cannot and will not ever be replaced by social media based therapy.

What can go Wrong with Therapy-Based Content Creation

Inherent in using social media for psychological care content are issues of privacy and confidentiality. To uphold these standards, the American Psychological Association published its own Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct effective in 2003.

Standard 5.04 references media presentations; the code states “When psychologists provide public advice or comment via print, Internet, or other electronic transmission, they take precautions to ensure that statements (1) are based on their professional knowledge, training, or experience in accord with appropriate psychological literature and practice, (2) are otherwise consistent with this Ethics Code, and (3) do not indicate that a professional relationship has been established with the recipient.”

The code is not to be taken lightly, and it is clearly stated that breaking any of the terms listed can result in loss of license or lawsuits. However, navigating the digital world with these rules in mind is an additional challenge that often makes lines blurry and potentially easier to cross; this is why institutions, private practices and individuals are implementing policies for proper social media use.

“A Therapist’s Guide to Ethical Social Media Use” written by Crystal Raypole on GoodTherapy.com while she was still Senior Editor emphasizes the importance of maintaining boundaries – similar to what Shindo said. The Good Therapy blog is a reputable resource curated by doctors, licensed professionals, and mental health experts.

For therapists like Shindo who use media to market their practice, Raypole’s guide says to “remember your likes and comments are often public, interact with other therapists carefully, avoid interacting with posts that could be unprofessional, and consider preventing incoming messages.”

Shindo ensures he stays within these boundaries by practicing social media sharing in moderation. In doing this, he protects both himself and his patients.

“I will share little snippets of my life, but I’m not going to put all of my business out there,” he asserts.

If best practices like these are maintained as the world moves increasingly towards complete digitization, the integrity of the industry will still be maintained along with it. But, only time will tell.

My Q & A with Brandon Shindo, where we discuss telehealth, social media therapy, and his personal methods of content creation.