Nostalgia: a wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary

The Power of the “Good Old Days”

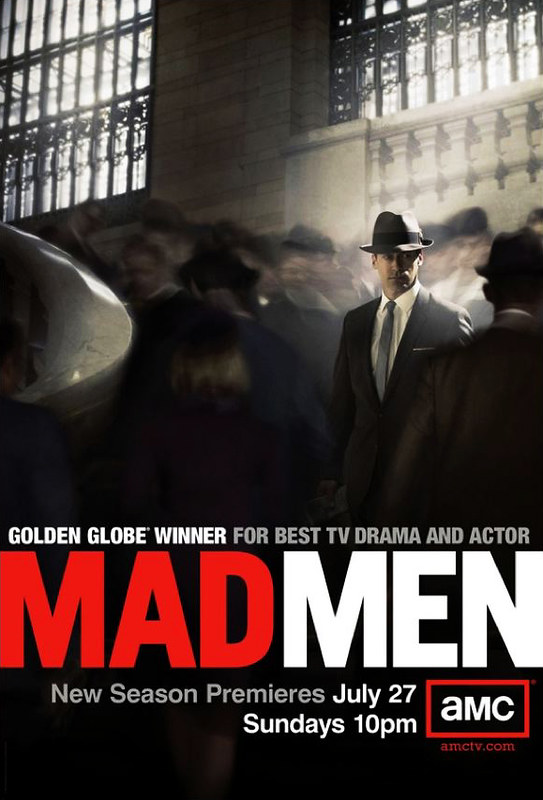

Nostalgia: it preys on our emotions and inspires us to hunt for pieces of the past and seek out the “good old days,” whether we as individuals personally experienced them or not. This human tendency is precisely why television hits like “Mad Men,” “Stranger Things,” and “Hollywood” enjoyed the immense popularity they did, and why film studios continuously give their audiences more and more content that romanticizes the past. Nostalgia industry in entertainment alone is responsible for millions of box office earnings annually.

Contributions from Lola Clark, Leo Driessen, Lindsay Luchinsky, Ada Tomczuk, Jennifer Veith, and Marek Zaleski

The word “nostalgia” holds a negative connotation at its root: “nostos” meaning return and “algos” meaning suffering. While this return to suffering can certainly be an uncomfortable journey to the past for some audience members, it is most often a highly desired catharsis and is frequently a positive, joyous, and sentimental experience.

Rebooted content is a prime example of the power of nostalgia. After a successful run from 1987-1995, “Full House” returned once more to televisions across the country from 2016-2020. The beloved “Arrested Development” (2003-2006) came back as well for a six year stint in 2013. “Star Wars,” originally released in 1977, has re-appeared to worldwide audiences and will likely continue doing so for decades to come.

According to a study published in the Science Fiction Film and Television journal, these returning series have “gone to great lengths not just to restart a once-profitable media property, but to do so in a way that recreates the original material as faithfully as possible.” By bringing back the same talent and creative teams, as well as using the same familiar aesthetics, set decorations, props, and costumes, these revivals craft a perfect specimen of what the journal labels as “transgenerational entertainment.”

This return to the past is a profitable choice for studios and production companies. According to a study published in the Journal of Consumer Research, consumers are likely to spend more money, or any money in general, on products that elicit nostalgic feelings. According to the study’s authors, when consumers were presented with nostalgic products they “were willing to pay more for products.”

As indicated in the study, film and television consumers are drawn to products that remind them of the past because they “foster social connectedness.” Other studies have shown that consumers of all ages are drawn to nostalgia and the age of the consumer does not impact his or her proneness to it.

The Downfalls of Restorative Nostalgia

The nostalgia industry is not unanimously viewed in a positive light. It can lead to inaccurate and problematic portrayals of the past, also known as restorative nostalgia. As defined by author Svetlana Boym, restorative nostalgia is “a politically reactionary mode that romanticises the past by refusing to critique or even acknowledge this earlier period’s negative aspects, and presenting it as an alluring retreat from an implicitly less desirable present.” It celebrates aesthetics of the past, such as a beautiful 1980s suburb, without mentioning the toils and hardships of the time, such as race and gender based inequalities.

The Netflix series “Stranger Things” exemplifies the problematic aspects of restorative nostalgia because it does not critically engage with or examine the cultural, political, or social aspects of the decade it celebrates. It centers around a friend group in 1980s Indiana that unravels supernatural mysteries and government secrets in their small town. The series recreates the cultural politics of the time period without any scrutiny, lacking a depiction of the severe homophobic, sexist, and racist issues present. As described in the previously mentioned Science Fiction Film and Television journal, fan reactions to content that employs reflexive nostalgia intensify the issue at hand. The journal explains this phenomenon by stating that “in evangelising about the show’s many qualities and ‘spreading the love’ on social media, we also choose to overlook the most basic political and ideological positions.”

For members of the film industry, nostalgia can be used as a method of gatekeeping. Nostalgia industry can be daunting, even suffocating, for filmmakers as it is direct proof that an old “tried and true” method works — why would Hollywood change a profitable method?

It may be hard for new visions and voices of diverse artists to be heard and accepted when old tropes, franchises, and concepts are constantly being recycled. Simultaneously, it can be difficult for creators of various backgrounds to find common ground in terms of the films and television shows they use as references. This creative language barrier is a frustrating obstacle at any point in a filmmaker’s journey, from lectures in film school to the development process for a feature film.

Los Angeles-based filmmakers and film critics reflect on their experiences with the nostalgia industry

Patricio Ginelsa

Patricio Ginelsa is an award-winning Filipino American filmmaker with several years of micro budget film directing experience, as well as an extended career directing music videos, most notably for the Black Eyed Peas. Ginelsa graduated from the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts with a film production degree in 1999. His latest project “Lumpia with a Vengeance” was an eight year long labor of love and recently won the audience award for Best Narrative Feature at the Hawaii International Film Festival.

Ginelsa recalls his days at USC’s prestigious film school as an exciting and uncertain time. While some of his professors encouraged bold creative choices and new stories, he frequently felt discouraged when he pursued less mainstream visions. In particular, Ginelsa said multicultural perspectives were frequently dismissed or passed over without consideration.

“I think people are more open-minded now for these stories, and there’s more of a playground — more streaming platforms now to do it,” said Ginelsa regarding his perception of his status in the industry. “I’m hoping that people out there are passionate enough and convinced to do it, because back in the day, it was hard to find people who wanted to make content like that.”

Although industry tastes and standards have certainly changed, Ginelsa made it clear that many challenges still remain. Resistance to take on these projects remains a challenge. When it comes to developing and producing content from a different era, Ginelsa believes that most creators aren’t cognizant of the brunt of responsibility they’re accepting. Throughout his career, he’s felt a lack of dialogue most significantly in the music industry where artists frequently want music videos with various geographical, cultural, and period choices that are not usually as simple as a design or directing choice. Ginelsa recounted how he’s had to explain why certain chosen aesthetics and styles cannot be used because they may be appropriative.

“You know, it’s our job to sell CDs and popularize the music,” said Ginelsa. “But for me, my responsibility as a filmmaker was to help teach or share something about the setting, both time and place.”

Ginelsa would like to see blockbuster franchises and the never-ending classic Hollywood cycle of reboots step aside and save space for new, progressive narratives. He is a self-proclaimed huge fan of “Minari,” about a Korean American family chasing the American dream.

“That’s an amazing, authentic film. I’m glad that it is winning awards, because that will just make it easier for filmmakers who want to do that, to do their own movie,” said Ginelsa after the film’s recent sweep of awards and nominations. However, he said, “There’s always going to be resistance.”

Jason Squire

Jason Squire is a professor at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts, a film critic, and an industry expert with experience in business practices, global industry, and audience issues. He is the author of “The Movie Business Book” and the creator of several cinema and media studies, including USC’s Marvel Studios Class.

According to Squire, Marvel actively capitalizes on the value of nostalgia when it comes to the films they slate for release, which manifests itself in two complimentary ways.

“One is the use of nostalgia because you’re doing a period piece, such as the opening segments of Captain Marvel with the Blockbuster video store or Guardians of the Galaxy with the tape deck. That’s so important to the story point,” said Squire, sharing a perspective cultivated from numerous conversations with filmmakers, writers, and studio executives. “And on the other hand we have the general nostalgic connection to Marvel because it is multi-generational in terms of movie audience.”

Originally, the studio, founded in 1993, started with only a sliver of the fanbase it can claim today. When the first phase of films was announced, the only audiences who responded were the ones that grew up with Marvel comics.

“There were about only two generations that grew up with the characters and were fans of the comic books,” said Squire. “All of that was, of course, totally repurposed for the current audience in their movies and done in quite a brilliant way.”

While most studios follow drastically different creative models, Marvel frequently takes chances on inexperienced directors producing immense projects. This studio aims to shed the old Hollywood formulaic method for making successful films, which includes recycling the same talent and repurposing profitable tropes. By constantly hiring industry newcomers to spearhead the projects, a fresh vision is guaranteed — a risk that continues paying off with the release of every film. As of November 2020, the studio had accumulated a worldwide box office revenue of $22.56 billion. Each individual film in the Marvel Cinematic Universe averaged an estimated revenue of $980.5 million.

“The studio content often gets a bad rap for being, you know, homogenized and because it’s expensive, it has to be bad,” said Squire about the stereotype surrounding studio spending. “The so-called new voices are essential to the future of the industry and the smart executives know that, and they don’t elbow them out in order to make some crappy remake.”

Christine Weatherup

Christine Weatherup is an actress, director, and screenwriter. As a Los Angeles native, she grew up at the epicenter of the film industry, wielding an encyclopedic knowledge of its ins and outs. She had been featured in “Watchmen,” “Grey’s Anatomy,” “Mad Men,” and “Westworld,” as well as in several web series and theatrical productions around the Los Angeles area. Over the past few years, Weatherup’s love for acting has been overshadowed by her passion for writing and directing, which she hopes to continue pursuing.

Weatherup wrote and directed “Killed In Action,” a short film about a veteran delivering devastating news to a housewife during World War II. The intention of the film was to focus on narratives that are frequently omitted in war-related films and television, despite the immense popularity of the genre.

“I wanted to explore questions like what are women doing? Usually when you see a World War II film, it’s focused on men on the battlefield,” said Weatherup in regards to her passion project. “Or you see the woman in the locket, but she has no inner world or anything beyond that.”

Weatherup’s idea for the film was inspired by her grandfather, who was a veteran and refused to share his stories and memories from the war, effectively making Weatherup’s imagination run wild. However, that curiosity soon found a different focus as she continued exploring the premise and doing more development research.

“I found myself curious about exploring my grandfather’s experience. But moreso, nobody ever talked about my grandma’s experience,” said Weatherup. “I can’t help but see it through my own eyes and wonder what those years would be like. I couldn’t think of any film or television show that did that.”

Similarly to other progressive, passionate members of the filmmaking community, Weatherup rejects the formulaic tendencies of old Hollywood and advocates for a turning of the tides in favor of younger, underrepresented, and unknown artists. She believes that an effective system from the past is not necessarily a superior one.

“Certain projects that I think are the most exciting right now are ones that are coming from voices that we haven’t heard before,” said Weatherup. “I think part of what is so exciting about them is that they take these certain formulas and things that are a part of our cinematic DNA, and find a new way to tell that story.”

Weatherup agrees with Ginelsa about the responsibility that artists must realize when approaching work from other periods. Artists are given a platform and an audience, both of which come with a sense of duty and accountability.

“Different artists can approach it through different ways. I think that sometimes by holding really true to the authenticity of the time but then shining a light on a story we haven’t seen, or shining judgment on a fact that we haven’t judged as harshly, is a way that an artist can speak out,” said Weatherup. “Or thumbing your nose at what the actual history is and crafting an alternative history.”

Drew McClellan

Drew McClellan is the Senior Program Specialist and Department Chair of the Cinematic and Visual Arts departments at the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts. He serves on the LACHSA Foundation Board and formerly taught at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts while attending the graduate filmmaking program. His professional credits have aired on Netflix, Viacom Networks, and international film festivals.

As an instructor to young, hopeful filmmakers, McClellan is glad to be a part of the flourishing filmmaking community during such a pivotal time. The industry’s mainstream standard of homogenous content is slowly shifting to a more diverse array, a change which McClellan hopes to be the paradigm of entertainment in this century. Filmmakers and creatives have been calling for this change for decades, urging studios to abandon their habits.

“There’s a lot of minorities that are coming forward and saying, ‘Look, we have stories that we want to tell that don’t necessarily fit the sort of stereotypical model that has been utilized throughout the history of Hollywood,’” said McClellan.

Although the change is slow, it’s clear that no one in the industry can stop the forward momentum. McClellan predicts that in the age of streaming services, gatekeeping as a barrier of entry will slowly be eradicated.

“You’re beginning to see a shift because all of these streaming networks, Amazon, Netflix, Disney Plus, they need content. And so they’re really having to stretch in order to integrate different types of stories,” said McClellan. “Narratives about the whole spectrum of different cultures, not just a slim window of difference in a very specific, stereotypical way.”

Additionally, the change is prompted by more diversity in positions of power throughout Hollywood. These executives can see the demand for new voices from the public and fill their slates accordingly.

“We’ll begin to see a very diverse array of experiences brought to the forefront because there is an audience. In the past, the gatekeepers created a very limited audience, meaning a finite amount of studios and cable channels,” said McClellan.

Nostalgia industry will never be abolished, nor does this article advocate for that. However, there must be a conversation undertaken in the entertainment industry about the responsibilities filmmakers sign on for when undertaking these projects.