It’s not something we mortal beings tend to discuss casually, or frequently, yet it’s the one of the few things that unites all of us. The fact is, none of us can escape death.

“Death and taxes. Those are the only two things that we can count on,” said USC Professor Judith Axonovitz, paraphrasing Benjamin Franklin’s famous quote.

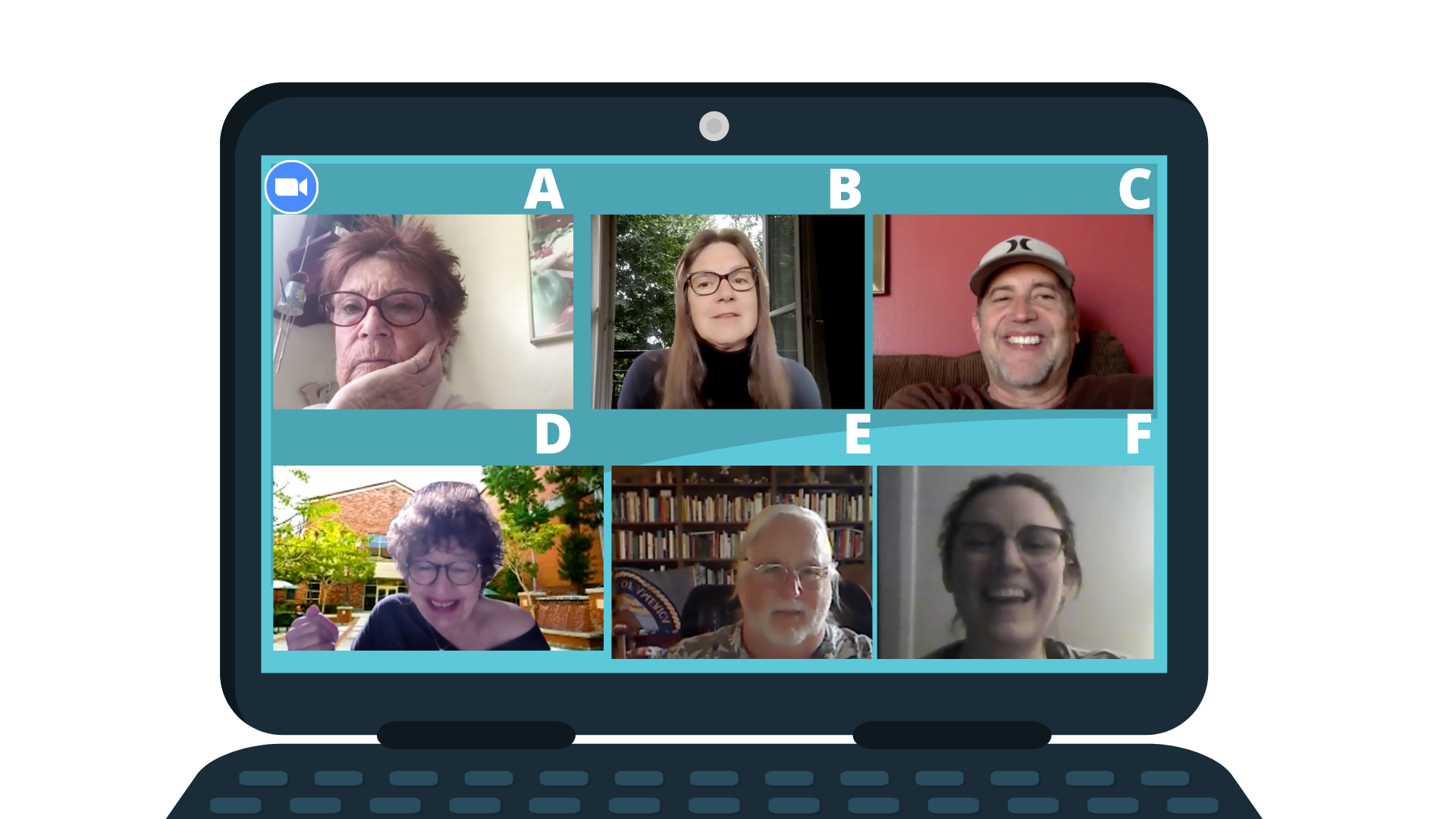

Despite taboos that may hinder us from even discussing the concept, there’s a certain slice of our population who enjoy talking about their inevitable expiration. On one Tuesday in February, some of them flooded into a 10am Zoom meeting. Spirits were high, as faces formed a grid. It felt like a gathering of old friends from California, Oregon, Connecticut, Florida and even Vancouver, Canada.

This was not a reunion, though.

Sponsored by Mission Hospice of San Mateo, this meeting was the virtual version of what’s called a “death cafe.” According to deathcafe.com, the formal definition is “a group directed discussion of death with no agenda, objectives or themes. It is a discussion group rather than a grief support or counseling session.”

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this particular death cafe, which would have normally been held in-person, has been hosted online since March 2020.

TO LISTEN TO A PODCAST SUMMARY OF THIS ARTICLE:

“A death cafe is a safe environment for two hours,” said 71-year-old bay area and North Carolina resident Jan Brewer, who started going to death cafes in 2015, and Mission Hospice virtually when the pandemic hit.

“Death cafe folk have big hearts,” said Jack Fong, a professor of sociology at Cal Poly Pomona, who has studied death cafes extensively and wrote a textbook called The Death Cafe Movement. “

“These are contemplative people who are seriously contemplating their mortality,” said Fong.

“We’ve got experience with [death] and we’re willing to talk about it. It allows us to have a fuller life. We get to live every day to our fullest, knowing full well that you know, we can drop dead any second because it is right here in our face. We’ve allowed it to come into our reality,” Brewer added.

Perhaps some of what makes death cafes different from a grief therapy group or seeing a psychologist, is the method and the price. Participants can drop in and out (made even easier by the zoom platform), don’t need to be grieving anyone in particular, and pay no fees.

Though some death cafe leaders are psychologists and hospice workers, technically, anyone can start a death cafe, as long as they have a host/facilitator, a venue with refreshments (at least, pre-COVID), and participants who want to talk about death. Hosts can publicize their events on deathcafe.com, which lists all registered death cafes and their zoom/RSVP links. In exchange, hosts agree to talk to the press and others about the death cafe movement and operate on a non-profit basis.

Here’s what the process looks like to find a death cafe meeting to attend on deathcafe.com:

Participants come for a variety of reasons. Some are on the verge of death themselves, others lost a loved one. Recently, a new type of participant appeared, “death doulas.” That’s a new career in the end-of-life industry, aimed at guiding someone through the dying process. Some just come to listen and learn.

Gemma Norburn, a mortuary technician based in East London and a death cafe leader for three years, said the rise in death cafes may be linked to the “death positivity movement,” which also came with the birth of the death doula career. Norburn said that trend does not advocate for death, but rather tries to create a climate “open to discussing it, and trying to aim for the best death, by talking about it and accepting that that is going to happen one day.”

According to Norburn, no two death cafe meetings are the same. Topics in these meetings range from existential ponderings of the afterlife, experiences with angels and ghosts, ethical scenarios for assisted suicide and cryogenics, and the logistics of making a will. End-of-life wishes, a common issue according to those who have spent years working by the bedsides of the dying, also come up. Experts advise that making a plan, which a death cafe can help facilitate, may allow for a smoother and more enjoyable end-of-life.

Curious about the types of conversation and stories that may arise from a death cafe?

It’s against the cafe rules to recording a meeting, but these are personal snippets from interviews collected, to catch the drift. Think of each story as a “mini” death cafe itself. Click on the audio clip with the picture’s corresponding letter.

A) Jan Brewer (71-years-old)

B) Susan Barber (63-years-old)

C) Dr. Brad Christerson (57-years-old)

D) Judith Axonovitz (74-years-old)

E) Dr. David San Filippo (68-years-old)

F) Gemma Norburn (33-years-old)

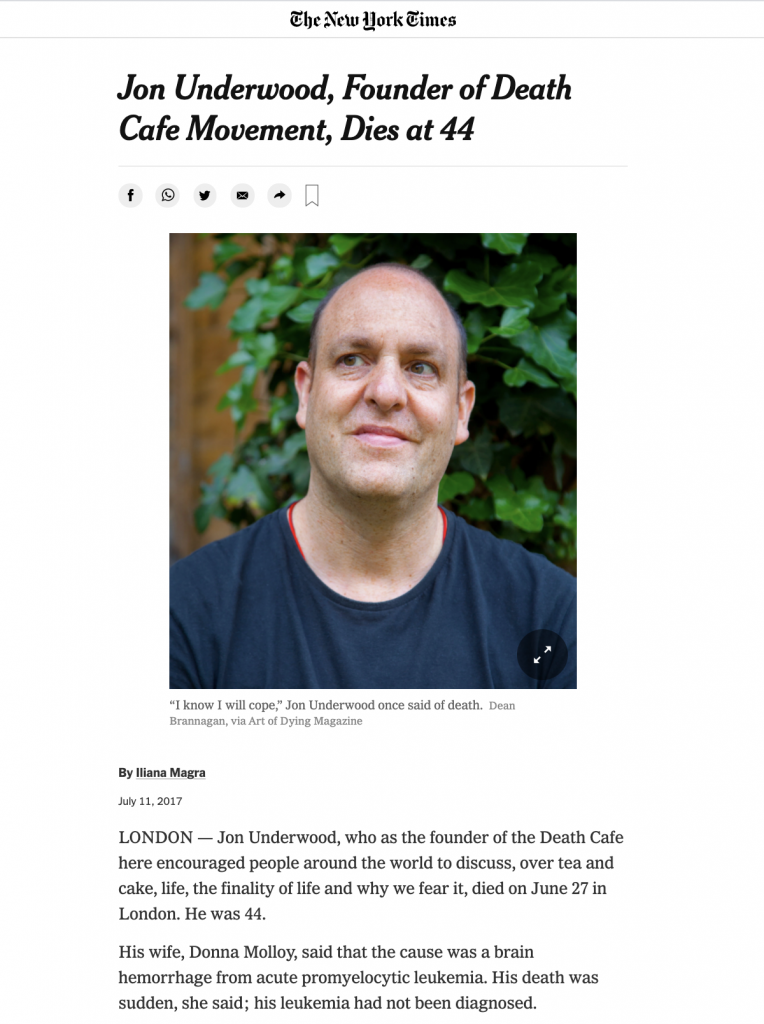

THE HISTORY OF THE DEATH CAFE

The birth of death cafes, actually go back to 2004, when Swiss psychologist and anthropologist Bernard Crettaz started the first “café mortel.” In 2011, U.K. web designer and self-designated “death entrepreneur” Jon Underwood heard about Crettaz and his cafés and hosted his first death cafe in the basement of his house with his mother, a psychotherapist. The “tea and cake” that is traditionally eaten at most death cafes around the world comes from the London location of Underwood’s first meeting.

In a 2013 interview with NPR, Underwood talked about Crettaz’s influences, “In continental Europe, there’s a tradition of meeting in a public place to talk about important and interesting subjects … So there’s a café philo, which is a philosophical cafe, and a café scientifique. And Bernard Crettaz, he’s a Swiss sociologist, [who] set up a café mortel, or death cafe.”

Underwood died unexpectedly in 2017 at 44 from a brain hemorrhage caused by undiagnosed leukemia. In his final years, Underwood helped spread the death cafe movement worldwide, from one cafe in 2011 London, to now over 12,450 Death Cafes in 78 countries, according to the death cafe website. If 10 people came to each cafe, that would be 124,500 participants total. Death Cafes are most popular now in Europe, North America and Australasia.

Underwood’s death hit the cafe community hard, said Betsy Trapasso, a Los Angeles grief worker, self-proclaimed “end of life guide” and one of the original “first five” American death cafe hosts. “John did a beautiful, beautiful thing, you know, just completely grew and took off,” said Trapasso.

It was Underwood who back in 2013, over Skype from England, pushed Trapasso to open up a death cafe in her house in Topanga, when no cafes or restaurants in Los Angeles county were willing to host her events. “People were like, no, like this thing called death? Like, we’re not going to let you have a cafe,” said Trapasso.

Besides her cafe in Los Angeles, other original cafes in the U.S. started in 2013 were in Albuquerque; Seattle; New York City; St. Joseph, Missouri; Atlanta; San Francisco; San Diego; and Ann Arbor, Michigan. The first Death Cafe in the US was held by Lizzy Miles in Columbus, Ohio in 2012.

She said social media was the key to the movement catching fire after that. One of her Twitter posts attracted the attention of a Los Angeles Times reporter, who came and wrote about her first meeting. The article on tmade the front page of the LA Times. Along with the article, a huge photo of a poster in Trapasso’s house, showing a diverse array of spiritual icons and gods and goddesses, such as Jesus, Kuan Lin and Buddah, was featured.

The article happened to be published on the same day as the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.

“It was really comforting, like, I don’t know, divine forces were at play, because Jesus is never like on the front page of the LA Times. It is very crazy how that worked out,” said Trapasso.

After the article, her meetings went from zero to four or five times a month. She didn’t continue to hold them in just her home, and instead drove around LA County to find locations to host the meetings.

“I wanted to go to every neighborhood, cover other cultures, cover all the religions, cover all the spiritual bands, cover all the races, the classes,” Trapasso said. Soon, other individuals started to host, and the meetings expanded to residences in Santa Monica, Calif., Santa Clarita and Pasadena.

Trapasso has not hosted online meetings during the pandemic. Her in-person meetings were unique from other cafes, in that she kept them very small, around four or five people. She organized exactly which dishes everyone brought, encouraging participants to bring dishes that had meaning to them or their family. It was that intimate feel that compelled her to hold off on online cafes.

“What Betsy [does] with the death cafe [is] creating the space to understand more healthily, mortality … without the vulgarity, without the market selling you fast coffins at a Costco checkout, or without medicine treating you simply as a dial that they adjust with dosages in medicine,” said Professor Fong, who was introduced to the cafe space by Trappasso.

Norburn originally hosted her cafe in what she said was a “lovely little cake shop.” Norburn said changing to the virtual platforms and promoting her zoom calls through social media has significantly increased her number of participants. Meetings in-person generally averaged around five or six participants, but Norburn said zoom meetings bring in around 20 per session. She said other café leaders have reported the same for their meetings.

When the cafes went virtual, it didn’t change café enthusiast Jim’s attendance. In fact, he went deeper into the movement and, once he discovered zoom, he started going to meetings around the world, as he described it, “obsessively and compulsively.”

THE LOGISTICS OF A DEATH CAFE – ALL “I’S,” NO “YOU”

Participants like Jim can easily jump into discussions across the globe because the rules are similar, and simple at most meetings. For instance, no one can give another participant advice and it is recommended to only speak about your personal experiences.

“That’s what I love about death cafes is that people are able to voice their ideas. And even if they’re very different from other people’s ideas in the death cafe, people can believe different things and be received,” said Susan Barber, the creator and current leader of the Mission Hospice death cafe.

“We pretty much stay away from religious topics,”said North Carolina café participant Brewer. “Immediately I hear the word Jesus, and I hear the word ‘you’ and I go away,” she said. “It’s like a 12-step meeting. No crosstalk, no advice giving, none of that ‘you,’ sh*t.”

From her perspective in the U.K., Norburn believes that, although religion can provide community and be helpful to someone going through a tough time, “there’s a certain amount of pressure on people to behave in a certain way because of religion and to do certain things because of religion. And I think it can kind of like box people in. We all know that grief and bereavement … don’t really fit into nice clean boxes,” Norburn added.

Brewer, the daughter of a preacher in the deep south who considers herself “a recovering baptist,” said all she had to do as a child was “use the word I or me and I got knocked across the room.” Now, in the death cafes, she appreciates that participants are encouraged, if not required, to speak about personal thoughts and feelings.

“When you go to a death cafe that you’re not told what to do, but you’re encouraged to conceptualize your way out of things,” said Professor Fong.

COVD-19, THE ZOOM WORLD, AND DEATH CAFES

As many people went online during lockdowns for death cafes in the last year and a half, more than half a million Americans died because of the coronavirus.

Susan Barber, the creator and current leader of the Mission Hospice death cafe which has met once a week since the beginning of the pandemic, said the virus may be behind the larger number of people participating in death cafes because it has, in her words, “removed the veil on death.”

Dr. David Schonfeld, the director of the National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles said that people may also be using the pandemic as an excuse to begin a long overdue conversation, “I think if you go to a death cafe, you can talk about death and grief without having to be labeled someone who’s grieving. And I think that’s just a lot of people right now because I think most people have someone they know who has died. And so, you don’t really stand out. But I don’t know if that’s the same, for example, if there’s been an earthquake somewhere or other types of crisis events,” he said.

Americans have been exposed to more death and a greater magnitude of death due to the pandemic, but in a way that may be harmful and unnatural, said University of Notre Dame sociology doctoral candidate Isaac Kimmel. He believes in-person funerals and end-of-life events are an integral part of the grieving process.

“Physical co-presence puts people in sync with one another in a physiological way. When we’re co-present and participating in a ritual, that really reinforces the collective understanding of what we’re all going through … that helps us to learn and feel a sense of solidarity with one another. We can understand traumas, or triumphs, or anything else, in a way that’s really well-established,” Kimmel said.

Kimmel questions if death cafes can provide the same solidarity and processing, but says they are “an innovative way to fill that gap,” especially when in-person meetings are impossible.

Dr. David San Filippo, a professor at National Louis University in Chicago who specializes in death and dying, said the major transition of our lives and relationships online could actually make general death anxiety, a common fear addressed in cafes, worse.

“Death is a personal thing. It’s also a social thing. I’m really concerned about the future, just because of the depersonalization that’s going on,” said San Filippo. “Yes, you have friends [online]. But it’s a two dimensional friend. One of the foremost things we hear from people who are dying or who are fearful of death is to be alone. We also thrive best in groups,” he added.

Dr. David Schonfeld believes death cafes have thrived because of the lockdown isolation. “You have really over a year of social isolation, so I think people are looking to connect in venues that are virtual in a way that they probably wouldn’t if there was a different type of crisis,” he said.

NATIONAL MOURNING IN HISTORY

Some death café leaders, who have decades of experience working with those on their deathbeds and those who are grieving, said the rise in support groups like death cafes appears to be similar to other times of national mourning, including the AIDs crisis and 9/11. Barber notes though, that during the AIDs crisis, those support groups were specifically for those with AIDs and caregivers. She says the general public didn’t really care, other than to keep those who were suffering from AIDs away from them. Trapasso says it was the LGBTQ communities who started a variety of support groups and gatherings for their communities. In Los Angeles specifically, Louise Hay started a gathering called “The Hayride” which supported those affected by HIV and AIDS. Trapasso also notes that other similarities between the AIDs crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic were crises in the medical world at the beginning of each event, over not knowing exactly how each disease was transmitted.

Though COVID-19 has caused significantly more deaths, many have also drawn comparisons between the pandemic and 9/11. Sociology doctoral candidate Isaac Kimmel said that what made 9/11 so striking for our country was that it was simply easier to process as a collective identity.

“It was so startling and so public,” Kimmel said. “It was very easy to use 9/11 to draw sharp collective boundaries between the victims and the aggressors between the nation and outsiders, between patriots and terrorists, right. Whereas, with COVID. It’s like, you know, first our president tried to make it a Chinese virus, a clear enemy.”

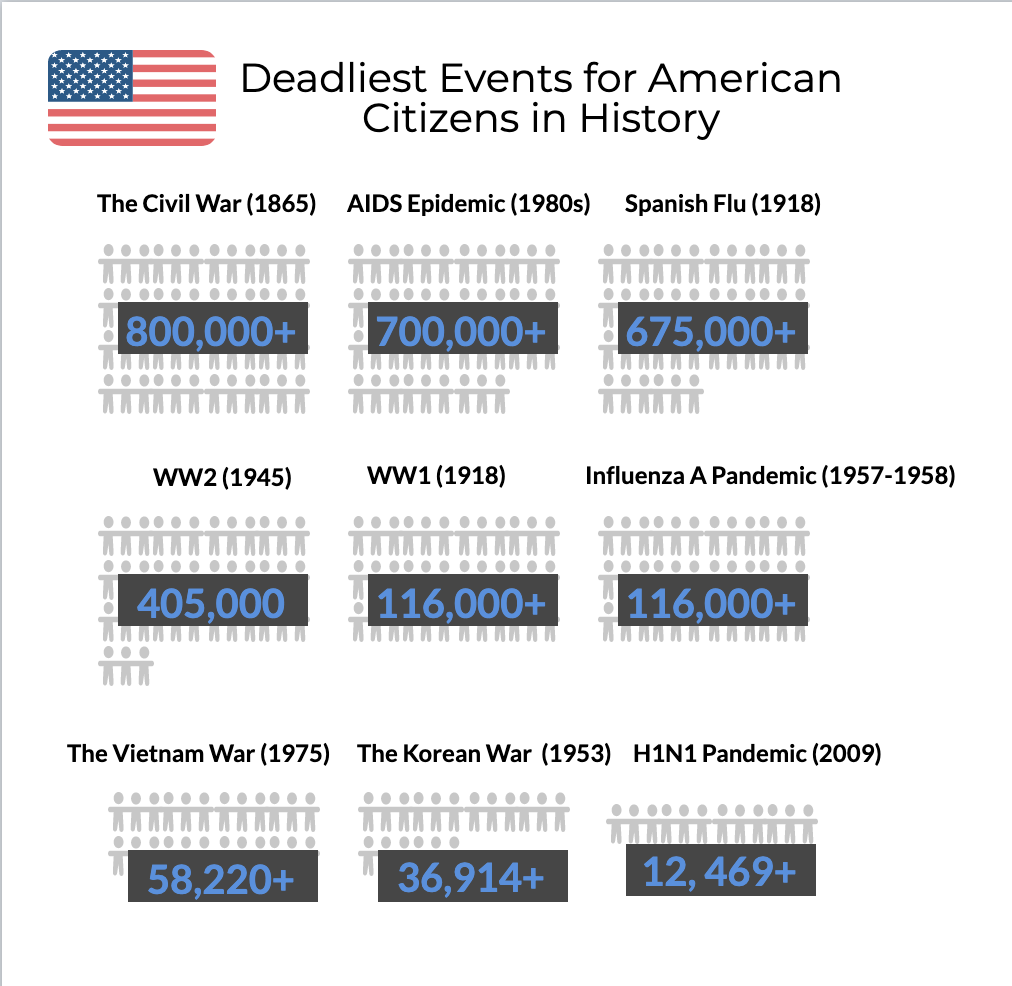

To understand how deaths can compel us to confront the impact of those events, here’s how the coronavirus pandemic compares to other periods of mass casualties and deaths in America.

*All death toll numbers estimated

*Numbers sourced from Britannica

[ DATA AT A GLANCE: From a historical mourning perspective, the coronavirus pandemic casualties have been monumental, but COVID-19 is not quite number one. The Civil War holds that title, with an estimated death toll ranging from 600,000 to 850,000 Americans. That’s almost a tie with the HIV/AIDS epidemic which has claimed about 700,000 American lives. The September 11th attacks (which killed 3,000 people) are often included in lists of events that led to mass mourning. To put that in perspective, though, during the deadliest day of the pandemic (September 18th, 2020) 3,660 Americans died from the virus ]

THE BENEFITS OF PARTICIPATING IN A DEATH CAFE

Besides helping process a mass casualty event, a death café can have strong positive impacts on someone’s life. There’s a reason why participants keep coming back, despite the morbid, and presumably unappealing, subject matter.

To those who may call the conversations dark, Susan Barber, creator and leader of the Mission Hospice death café, said it’s not so much what participants learn about death, as it is what they can learn about life.

It’s not so much what participants learn about death, as it is what they can learn about life.

“Our life is given to us so that we have an opportunity to prepare for death,” Barber said. “How do I want to show up at my death whenever it is? With a lot of unresolved things, and a lot of anger, unforgiving? Or do I have opportunities now to make sure that at my death, those are not the things that I am concerned about.” Barber said death cafes give participants that opportunity to evaluate what’s most important, no matter how old or close to death they are.

UK-leader Norburn said death cafes encourage people to live their lives to the fullest. “That can sound really cheesy. But it does mean that to some extent you’re enjoying your life now for what it is because you accept that one day, you’re not going to be here,” she said.

Dr. San Filippo, agrees with the effectiveness of death cafe philosophy. “ If you look at life, from a critical standpoint, you realize you don’t get out of this alive. So you may as well accept it,” he said.

If you look at life, from a critical standpoint, you realize you don’t get out of this alive. So you may as well accept it.

“People at death cafes look at life differently,” said participant Jan Brewer, who has learned to live a life of no regret through accepting death through deep conversation in the cafes. “I’ve made the commitment to myself, that every night when I go to bed, it can be my last day on earth. I’m clean and clear. I’ve said what I needed to say. I’ve lived the best day I can live. And tomorrow if I wake up, it’s another gorgeous, glorious day. And if I don’t, I have no regret. That’s my philosophy of life. And so, death cafes allow me to live that way. That’s how people in death cafes look at life,” she concluded.

Barber said one of the main lessons of the death cafe is learning to address the common fear and anxiety around death. Berkeley resident Jim, who has been going to the Mission Hospice death cafe since 2018, agrees.

Jim recalls the moment his anxiety around death sparked, when he saw his father lying in a coffin. “I’m sitting at the, at the funeral parlor. As the younger people are walking by, I have both visual and auditory thoughts, which are, I’m next up in that coffin. I went into a number of years of anxiety, death anxiety.” After that, he experienced another loss, his wife. “After that loss, I was scared to death to love and be loved. I was scared to death,” he said.

This anxiety started to affect Jim’s work as a psychologist, when clients would come to him for help on their own grief. “I said, My God, stop this, I do not want to deal with this. I do not. I didn’t throw anybody out of my practice,” said Jim, “but I didn’t want to deal with this.”

It took accompanying his own mother to her death years later, to find his personal peace. “She said to me, ‘Jimmy, in my experiences, the vast majority, when it’s time to be ready to face death, they’re ready.’ And that launched me into hospice,” added Jim.

After 20 years in hospice, he said the “fear hasn’t disappeared, I can be afraid of all kinds of sh*t. However, I can walk through it, meaning I have courage. It really brings me closer to living more fully, and to be present for living a meaningful life, which is a prerequisite to being prepared for the death of others and the death of myself.”

Fear hasn’t disappeared, I can be afraid of all kinds of sh*t. However, I can walk through it. It really brings me closer to living.

It was after Jim retired from his career as a psychologist and started volunteering at a hospice that he stumbled across death cafes. Jim said the hospice volunteer coordinator knew “he was not fulfilling my desire to spend more time with families and persons who were dying. And he said, ‘You know, there’s this death cafe. Have you been?’” Jim’s first death cafe experience was in Alameda, California.

Now he admits, he is a “lover of death.”

A caveat of the cafe space, is that “the people who attend death cafes tend to be the people who are quite open talking about death already,” said UK café leader Norburn. For her, though, some of the most rewarding experiences of leading a cafe come from seeing someone with an intense fear of death, or what Norburn calls a “bad relationship with death,” turn it into a more comfortable concept.

She recalls a woman who started attending her zoom death cafe during the start of COVID and who was quite fearful of the subject. After a year of being involved in cafe conversations, Norburn said that person now works as a volunteer in a hospital, sitting with people while they are dying, if they don’t have friends or family to do that.

“She started coming because she wants to understand why on Earth people would go to this thing and talk about death. It’s amazing that she’s gone on this real journey. I wouldn’t say she’s totally okay with it, but she certainly opened her mind up to the idea of thinking more about it and helping people at that time which is brilliant,” said Norburn.

DEATH CAFES, THE ROOT OF EMPATHY

The cafes don’t teach everyone to “love” death, or want to be around it frequently. Some café hosts said, if anything, they may simply teach how to let go of trying to understand and conceptualize death. In a time when so much is uncertain, that may be just what is needed.

Café leader Barber compares it to something as basic as exercising a muscle.

“I think being able to practice with these things about letting go in smaller ways is the same example about going to the gym and trying to pick up the 300-pound weight,” she said. “Practicing with letting go with smaller things that maybe don’t matter so much but I can say okay, I can prep just letting go that my hope is that on my deathbed that I’m able, at some point, let go there as well.”

After decades of talking to those who are in their final days, and those who are just curious, Barber reflects on what she has personally gained by opening the conversation on mortality and introducing others to the idea of the death café.

“I learned something new about myself, every single time I show up, because really, when people are at the end of their life, there’s no time for bullsh*t,” said Barber. “What there is time for is compassion and care. People can learn to build their capacity for compassion, they can learn to build their capacity for hearing somebody else who’s really different and has completely different ideas about them.”

“Now, as an old fart, it allows me just to be more authentic,” said Brewer. “We’re realistic when looking at death. We don’t do it based on fear.”

DEATH CAFES SPARK UNIFICATION IN A FEAR-DRIVEN SOCIETY

“There are theorists that write very clearly that our fear of death is the basis of all fear and anxiety,” cafe participant and psychotherapist Jim said.

There are theorists that write very clearly that our fear of death or fear, anxiety, is the basis of all fear and anxiety.

America is a fear-based society now, more than ever, which may contribute to tension, violence and anger in our country. Nailing it down to a basic psychological principle, the more we live driven by fear, the more we tend to be selfish, less trusting and more egotistical in our decisions according to the Neuroscience Education Institute.

“I mean, just look at the way TV is reporting on COVID deaths. It is so shock value oriented, nonstop. ” said Fong. “[We] fear our public spaces. Whenever we think of our public spaces, we have this kind of like, boogeyman out there that’s gonna kill us, rob us, rip us off, drive by shoot us, hit and run us.”

The non-judgmental atmosphere of the death cafe may help us take on not only our fear of death, but our fear of so many other things.

Death cafe leaders and participants agree. “Being around death, like sort of facing one of the biggest fears I had, really has allowed me to face other fears in a much healthier way,” said Barber.

Cafes could be the start of some sort of unifying tool, a sign of hope in a divided country controlled by fear. “Where do you find Americans, who don’t know one another, sitting down having food, respecting one another, you rarely see that in the community anymore.” Fong said.

America is only becoming more diverse, both culturally, and in our thoughts and beliefs. We can physically move ourselves to new locations, and through the internet, virtually be exposed to beliefs other than the ones in our own home community.

Sociology doctoral candidate Kimmel comments on the divided, political environment of America, and how the struggle between conservative and liberal often relates to the fear of letting go of old ways, and comfortable traditions.

“Which is not to say that the old way was any better because so many people were marginalized, right, and so many people were excluded. As individualism and even economic autonomy result as core values of a society, it makes it so that people are really disenchanted with old rituals and old senses of collectivity activity and shared meaning,” he said.

“We are such a diverse group of people here, we’re not homogenized, like a lot of some other countries are. So how do we have respect for the background and the mindset that people have to be able to have these big discussions and to talk about it?” said Axonovitz.

The challenge is to unite us as a country, as we only inevitably become more diverse in our religious and philosophical understandings of the meaning of life and mortality. Without some form of uniting, we risk the taboo around death increasing, and our fears of being alone in facing death.

However, death is a universal shared experience, so anyone of any background could come and talk.

Dr. Schonfeld remembers addressing parents concerns about talking to kids about death at a school presentation: “I think it’s part of it’s facing the fear, but it’s also talking about something of substance with people, whether they be strangers or people that you come to know. (The parents) said, ‘what happens if your child believes in heaven and another child’s parents tell them they don’t.’ That’s good to talk about, we have to as a society, learn that there are different viewpoints, and that those are respected. It’s okay to have a different belief system than someone else. Because if we just assume, we can’t talk about anything that’s controversial, then we create more controversy. Because then what happens is, we get polarized … where it’s okay not to agree with things.”

“That’s why you mix with people of different beliefs and backgrounds so that you can learn from it, not so you can convince them to do what you do, or what you believe. So I, yes, I mean, I think it’s part of building empathy as part of building community. It’s part of dealing with conflict, all of that becomes important,” he said.

As more Americans become less religious, Kimmel comments that death cafes could be a solution, as an “innovative way of restoring that sense of collective meaning and collective belonging. Deaf cafes are interesting in that they don’t have the same kind of established frameworks to draw on, but they pull off, or they they pull from these new modern expectations of, you know, subjectivity, and individuality and sharing your own experience as such, and allowing others to sort of sift through it for the things that they need.”

Professor Fong comments “the death cafe is not only about seeking answers for the afterlife, but seeking all of the themes that people use to assemble their interpretation of it.”

With death being a universal shared experience and death cafes promoting that listening atmosphere, there may just be something to learn from.

Fong said death cafes won’t provide the answers to harmony, simply because “no one’s going to give up their faith and run toward this quasi-bohemian movement,” but “I think there’s a greater capacity for the death cascade to be a global movement rather … to unite those who for much of their lives have felt that religion didn’t give them an answer, ” he said.

Death or politics, in a divided country, a death cafe could be the start of confronting the fears that may control us, which may be a benefit.

“Societies who can operate without being in fear, tend to do better because they can. Go fear fear causes doubt. Fear causes hesitancy,” said Dr. San Filippo.

THE ROOTS OF THE AMERICAN FEAR OF DEATH GO DEEP

Perhaps more harmful than the taboo around death, is our fear, or anxiety about it. This anxiety can be rooted back to a dramatic shift in how we dealt with it in 20th century America, according to sociology professor Brad Christerson, who teaches a class called “Death and Dying” at Biola University. Professor Christerson, as well as Dr. Schonfeld, Professor Fong, and doctoral candidate Isaac Kimmel break down that change in perceptions and priorities into six categories.

CAPITALISM : “In an agricultural economy, the more kids you have, and the more people you have around, the more labor you have. It made sense to bring more people in and live more communally. Under capitalism, and wage labor, people leave the home to go make money. Kids couldn’t work in factories anymore. Kids become a financial burden rather than an asset. So, communities get broken apart. People get more and more individualized. Particularly in the middle and upper classes, people just move for better opportunities. And so, you get more and more disconnected with your family members. Because people are so mobile and particularly the middle and upper middle classes. And then you’re just not around people when they die. And you’re doing things for your own career pursuits. This leads to that lonely, fearful interpretation of death.” – Professor Christerson

INDIVIDUALISM: “There’s not kind of one explanation of why death, why death happens and what happens to you when you die. When it’s individualized death isn’t just something that happens to all of us. You know, we’re all in this together. But now it’s ‘Oh, no, that’s so tragic that this happened to me.’ You’re like, ‘why did it happen to me?’ And, and people ask that when they get their, you know, their terminal cancer diagnosis, ‘Why me? Why is this happening to me?’ And, and that’s because we live in an individualistic society where we’re, we’re not thinking communally that ‘Oh, yeah, that this is just something that happens to everybody.’ – Professor Christerson

INDIVIDUALISM: “There’s not kind of one explanation of why death, why death happens and what happens to you when you die. When it’s individualized death isn’t just something that happens to all of us. You know, we’re all in this together. But now it’s ‘Oh, no, that’s so tragic that this happened to me.’ You’re like, ‘why did it happen to me?’ And, and people ask that when they get their, you know, their terminal cancer diagnosis, ‘Why me? Why is this happening to me?’ And, and that’s because we live in an individualistic society where we’re, we’re not thinking communally that ‘Oh, yeah, that this is just something that happens to everybody.’ – Professor Christerson

DECLINE OF THE LARGE NUCLEAR FAMILY IN AMERICA: “It’s a much bigger deal when one of those four people dies, right, or one of those five people dies, rather than if you’re living in a household with aunts and uncles and grandparents and bigger families. So, a lot of families had, you know, four to eight kids and expected to probably lose one of them. But when you have smaller families and nuclear families, it’s more devastating when one of those people dies.” – Professor Christerson

RISE AND FALL OF RELIGION IN AMERICA: “Previously, we would be embedded in these religious and cultural communities where we had shared and well established sets of norms and rituals for coming together and focusing on the common object of death and constructing common meanings around it and coming to understand it in a shared way. And, you know, like you were saying, that’s less true now, because religion is so much more individualized, it’s so much more atomized. So, you can’t rely on those shared meanings quite the same way because you don’t know that the people around you share them. Without them is a threat to our own awareness and existential comfort.” – Isaac Kimmel

MEDICALIZATION OF DEATH/THE DEATH INDUSTRY: “I think nowadays kids are actually exposed to death less than they were generations ago. In the past, kids grew up on farms, and people would die at home, funerals were at home, they were exposed to it, it was part of the natural life cycle, the life span was less, and then started putting sick people into hospitals and they die in hospitals where children can’t visit, so there’s been this removal of death from life experience. And I think some of the taboo of death started once we started to remove children from exposure and involvement in it, which is the reason why you have to have a death cafe, because you didn’t talk about it beforehand, but in other societies you would have.” – Dr. Schonfeld

DEATH IN MEDIA: “There’s a whole genre of film specifically, that capitalizes on creating the vulgarities of death. When you have really crappy foams or primetime films, where every episode there’s an explosion that kills someone, we’re in every episode someone a shot. We’re in every newscast someone has run over by a hit and run driver, if not shot by police. You have a sort of accumulation of toxicities toward death which I find to be very unhealthy. It makes us look at death as a less sanctified and sacred.” – Professor Fong

DEATH IN MEDIA: “There’s a whole genre of film specifically, that capitalizes on creating the vulgarities of death. When you have really crappy foams or primetime films, where every episode there’s an explosion that kills someone, we’re in every episode someone a shot. We’re in every newscast someone has run over by a hit and run driver, if not shot by police. You have a sort of accumulation of toxicities toward death which I find to be very unhealthy. It makes us look at death as a less sanctified and sacred.” – Professor Fong

TACKLING DEATH ANXIETY AND TABOO – THE BIGGER PICTURE

Aside from attending or hosting a death cafe, experts point to other ways we can face our country’s death taboo.

An easy start to bring up death in a familiar way with loved ones?

The arts, according to Trapaso.

Trapasso said art was a universal, and oftentimes the only way her hospice patients knew to process death, “I go to people’s homes, and they would say, ‘Oh, I love this song, or I saw this movie, right? Or I saw this play, or I saw something.’ So they could talk about death, kind of an artistic way, something that they liked, much easier than actually talking about death as like the reality of it.”

Axonovitz pointed towards death education in more college classes, and even elementary schools as a necessary solution, but said it won’t be easy. “There’s resistance by parents not wanting, you know, their children, whatever the age to talk about these things, you know, because then they have to confront it,” she said.

It can never be too early to introduce death to kids, according to Dr. Schonfeld, who said kids can conceptualize the idea of loss as early as six-months-old, “Once they start to develop object permanence, between six and nine months, they start playing peekaboo in every culture in the world. And it’s a game about death.”

It’s not just parents’ silence on death with their children, but also about how they talk about the afterlife, that’s a problem according to Schonfeld.

“Children can understand death is irreversible, but we don’t teach them that when somebody dies, they don’t come back to life. Kids will ask ‘what happens when you die?’ And they said, ‘Well, you go to heaven.’ And then they ask, ‘where’s heaven?’ The response ‘i’s in the sky … doesn’t make any sense. Then kids say, ‘Well, if you bury people in the ground, how do they get to heaven?’ There’s only two ways that I’ve seen kids come up with. One is [deceased people] come out when it’s dark, and that makes you afraid of the dark, or they’re invisible, and then they’re ghosts. And that’s also scary. So religious concepts tend to be much more abstract, it tends to confuse them … leads to guilt and shame,” he said.

Schonfled said there’s not a “right” age we should introduce death to kids, but suggested explaining it whenever the conversation pops up naturally.

“If they see a dead bird outside and they ask why isn’t the bird moving? You have a conversation that everything that’s alive eventually dies, and when they die, they don’t move anymore. Doesn’t have to be a long conversation, but they can learn the concepts through general discussion,” he said.

Schonfeld said the Amish had some of the most memorably effective ways of introducing death to kids and grieving in general, crediting this to the communities grounding in nature, particularly due to growing up on farms. “It is more accepted as part of the natural life cycle.”

IS THE DEATH CAFE A REAL SOLUTION?

Professor Fong sees the death cafe as a tool that allows Americans to think independently from the capitalistic and religious influences mentioned above. “What the death cafe opened up for me was this amazing tsunami of self-authored interpretations of mortality, freed from the influence of what I call the trinity: the mass media, the market, and medicine,” he said.

Professor Herbert Northcott, a professor of sociology at the University of Alberta, said he is skeptical about the effectiveness of death cafes. He teaches a death and dying class, and said after his students read a 700-page textbook and spend 39 hours of talking about the subject, the group is not any more prepared to deal with the reality of it.”

When a student in his class tried to get him to speak at a death cafe a couple years back, he refused. He said he didn’t want to participate in the enterprise.

To Northcott, the cafes are “an attempt to make something attractive, that isn’t attractive, to make something acceptable that we really have at some level can’t accept.” He believes that really can’t come face to face with death, until we do.

“How do we deal with existential threats … we dress them up, we find meaning, we find poetry, we find religion, we romantic love, being a good citizen, or parent, or we find philosophy. Maybe we use hedonism, partying as a solution. I see [the death cafe] as just one more pathetic attempt to keep death at a distance.”

Northcott finds it hard to distinguish between going to church and going to a death cafe. “In church, they acknowledged that they were going to die … unlike some religions, the death cafe focuses on the present. We don’t need God, we don’t need heaven or hell. But we need to focus on the present to make life meaningful. My argument is quick and dirty. It’s simplistic. People stopped going to church and went to death cafes.”

Professor Fong disagrees and said the movement never aimed to provide concrete answers, like religion does. “To say that death cafe is therefore another sort of religion is really a very lazy use of the term religion. If that’s the case, I can say, well, I think the real religion of America then is money. We spend our entire lives working for it. We worship money,” he said

Northcutt offered up optimism after his cynicism on the subject.“If people sitting there, drinking beer, wine and chatting and talking about this helps, okay, great. Whatever works,” he said.

San Filippo has similar thoughts as Northcutt. Death cafe or not, he thinks one can’t accept death fully no matter how many death cafes you attend, if you’ve actually experienced death firsthand.

“I think that they [can understand death] up here,” he said as he points to his head, “but when it happens [to them directly], they’ll feel it here,” he said while pointing to his heart. “They’ll understand the human experience.”

Professor Fong hopes the cafes might be a catalyst for discovering something greater beyond.

He views the movement as “a phase into something we have yet to figure out, perhaps into another horizon …now religious folks might say, hey, Dr. Fong, are you implying a heaven? Well, I do not think the physics we have at this time to answer that, but .. let’s say you’re the ultimate extremist atheist, you still can’t deny that our body, which is made out of matter, has given us this consciousness. So perhaps if this thing called the universe is out there, and it’s matter, maybe there’s a consciousness that our measly little brains are limited physics yet to fully illuminate.”

Perhaps the death cafe is a space for those grappling with the harsh reality of death, but it’s also a space for anyone else with just a trace of curiosity, willing to explore what could be beyond “our measly little brains.” Above all, the cafe provides strength through a community, and encourages its participants to find joy in everyday life and keep going.

“All the death cafes that I’ve attended, when I leave, I feel good. I feel kind of like, wow, I could handle this. I’m a human being that has the courage to deal with this,” says Fong.

For more information on death cafes, and how to start your own, or attend one across the world at no price, visit: https://deathcafe.com/what/

Natalie Ruxton is a student journalist at the University of Southern California. She is interested in all things existential, and recently started her own spiritual podcast, MINDF*CK, available on all platforms.

contact: natalieruxton@gmail.com

twitter: @natalieruxton, instagram: @natalieruxton

Front page gif credits to: deviantart.com and trans-lu-cen-cy