As they witnessed history on three different screens in two different time zones, separated from him by anywhere from five to 10.7 million feet, ranging from the quietude of a retirement home to the pandemonium of Wrigleyville, their minds all traveled to the same exact place.

Ray Ackerman’s daughters, Karen Witter and Cinda Klickna, were with him in his apartment at the Concordia Village retirement community in Springfield, Ill. Randall Ackerman, his son, was home in Alamo, Calif. Alex Ackerman, his grandson, was standing outside Wrigley Field, eyes glued to a small TV screen through the window of a bar charging $75 for admission — when it happened.

A weak dribbler up the third base line. A charging Kris Bryant, who gathers his feet and scoops it up. A panic-inducing slip and a subsequently relieving grin while still making the throw — a little bit high, but not too high for Anthony Rizzo to snag it, 108 years of heartbreak and agony ending as leather met leather in the back of his glove.

“The first call I made was to my dad,” Randall said.

“[He] was definitely front of my mind,” Alex said.

“Literally, it still brings tears to my eyes,” Witter said. “It was like a spiritual experience, you know?

“I mean, he had waited so long.”

How long, exactly? Just 301 days — and 98 years.

Measured by the sheer density of those 98 years, though, it felt like it could’ve been 98 more.

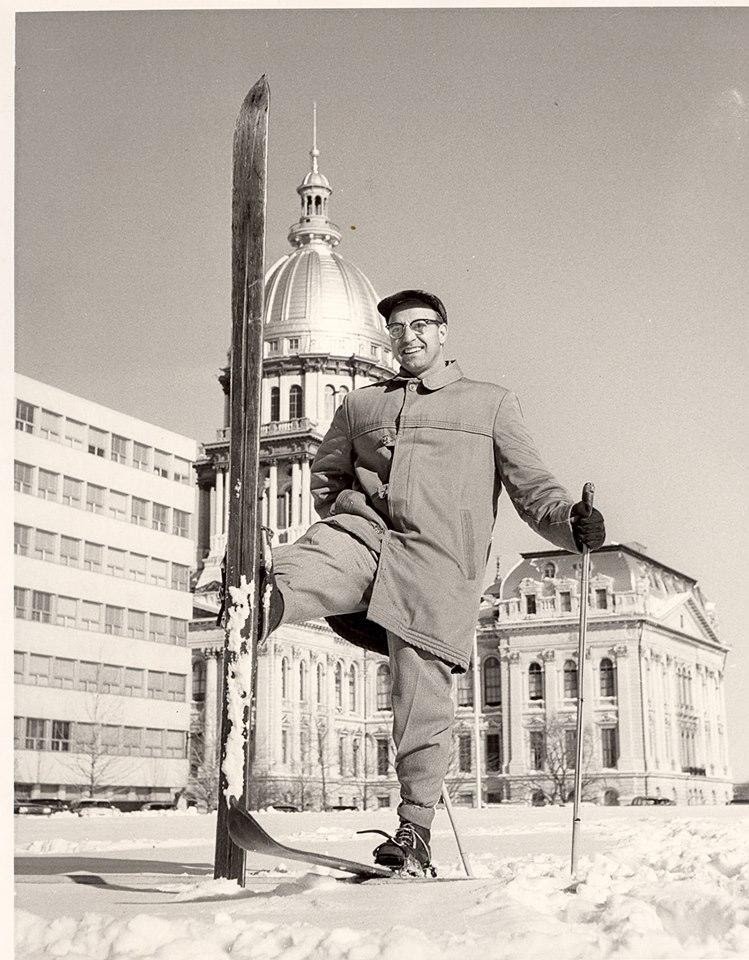

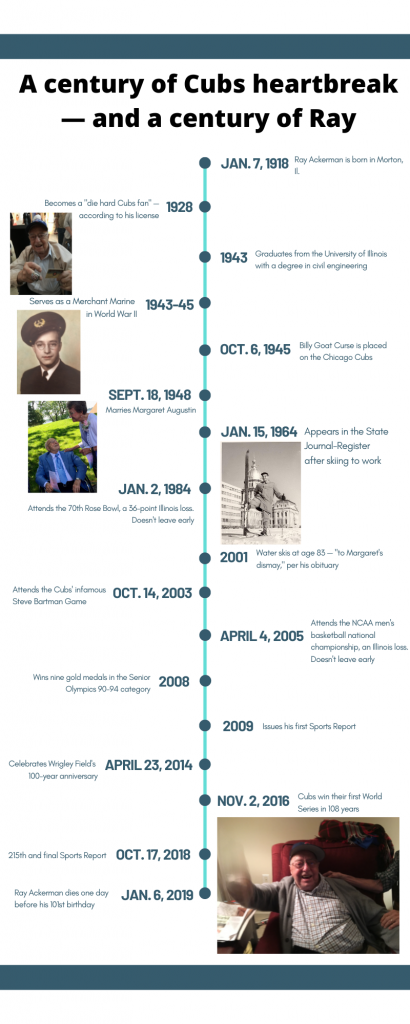

Ray Ackerman had done it all. He’d lived through the Great Depression. Served as a Merchant Marine in the South Pacific in World War II. Appeared on the front page of the State Journal-Register alongside Jackie Kennedy and the cover of the Chicago Daily News with Elizabeth Taylor for skiing to his job as an Illinois Department of Transportation engineer. (What else are you supposed to do when you’re snowed in?) He’d won nine gold medals in the Senior Olympics, competing, in his own words, “against every 90- to 95-year-old in Illinois that didn’t show up.” But those are just some highlights; a more exhaustive list can be found in his three-volume autobiography aptly titled “Grandpa — The Boy.”

There was one thing — and only one thing — he hadn’t done. He hadn’t seen the Cubs, the team whose insignia he carried everywhere on his “Die Hard Cubs Fan Since 1928” license, win the World Series.

He’d seen some milestones along the way, to be sure. Wrigley Field celebrated its 100th birthday four years before Ackerman did his own, and he was there for the occasion, snapping a photo with Miss Wrigleyville down on the field before the game. He’d been there with Randall for the infamous Steve Bartman Game in the 2003 NLCS — and the following Game 7, where the World Series drought officially hit 95 years. He’d seen his favorite player, Hack Wilson, drive in 191 runs in 1930, a feat about which — per a source familiar with the situation — he never stopped talking.

He’d just never seen them win it all.

“I guess I just remember the neverending being a fan,” Witter said of her father. “And — ‘Well, wait till next year.’”

The problem: “Next year” kept giving way to more and more “next years,” eventually morphing into “next decade,” “next century” and “next millennium.” Still, Ackerman never wavered. The license stayed firmly tucked in his wallet.

“He never gave up on them or threw the towel in,” his wife of 70 years, Margaret Ackerman, said. “No, no, he didn’t do that. No matter what. He didn’t then switch to the winner. He didn’t do that. He was still loyal to his team, the Cubs, through thick and thin.”

Perhaps no one has ever been more equipped with the emotional equilibrium required for Chicago Cubs fandom than Ray Ackerman. They say patience is a virtue, and Ackerman was indeed a virtuous man.

“Patience.” That word might surface more than any other in a typical conversation about Ackerman. “Patience galore” — along with fairness, honesty and giving credit where credit is due — was how his wife described his core principles.

He was patient with his grandkids, teaching them how to put bait on fishing hooks or stand up on water skis — foundational elements of two favorite hobbies. Klickna, Ackerman’s first daughter and child, went on to be an English teacher, so growing up, she hated math. But Ackerman would sit with her anyway, helping her with “stupid story problems,” never losing his patience when concepts didn’t stick.

“He just always would take time to work with you and not push you aside,” Klickna said. “He would just keep at it until we were successful or didn’t want to do it anymore.” (She did, however, recall one time he lost his patience with her, washing her mouth out with soap after she’d talked back to her mother.)

“The most patient person I’ve ever met” was how Randall described someone who saw plenty of Cubs losses but also a healthy dose of letdowns by their shared alma mater, the University of Illinois, yet never wavered in faith.

The two were at the 1984 Rose Bowl, where No. 4 Illinois lost to unranked UCLA in a not-so-nail-biting 36-point beatdown. They were at the NCAA men’s basketball championship game in 2005 against North Carolina, another Illinois loss.

No matter the score, though, the most patient person in the world refused to leave early. That was his sticking point.

Witter remembered one particular Illinois football game against Ohio State, which Ackerman refused to depart despite a three-touchdown deficit with less than two minutes remaining — circumstances almost impossible to come back from — and, for good measure, miserable weather.

Ackerman’s “never leave early” approach extended beyond sports. Two days before he died of heart failure from old age in January 2019 — and three days before his 101st birthday — he successfully lobbied his two daughters to wheel him to a Concordia Village staple: Happy Hour, where their favorite pianist would play, a Friday 4 p.m. tradition for Margaret and him.

“He was having a lot of breathing issues, and he had to have breathing treatments, and he would cough a lot and this and that. He was not doing well,” Witter said. “And Dad said ‘I want to go.’ And I said ‘You do?’ Cinda and I look at each other. We’re like, ‘20 minutes ago, we thought he might take his last breath.’ He says ‘No, I feel better now. I want to go.’ And it’s like, ‘OK … ’ So we wheel him out of there. We go over to Happy Hour.

“Saturday he’s not good, and overnight he died. So even there, to the very, very end, he just didn’t leave the game early.”

Ackerman actualized the adage that baseball is a metaphor for life. He seldom complained about either — the century of heartbreaking Cubs losses to which he bore witness, his general immobility in his wheelchair-bound final years.

That doesn’t mean he lacked opinions.

“He might complain about the coaching and the Monday Morning stuff and who should have done what,” Witter said, adding that he might express disdain about TV broadcasters from time to time before simply muting them and turning on the radio to supplement the visuals with his preferred announcers, a practice she always found peculiar. “But on things that related to him, he just didn’t complain.”

He was meticulous, a stats geek — for which the engineering background is likely responsible. He developed the nickname “Stats Ackerman” by keeping the scorebook at all of Randall’s youth baseball games, compiling everyone’s batting average ahead of the end-of-the-year party and, once, summoning an artist in his office to create a statistical visualization of that season’s doubles leader.

And, of course, as a fan — a father — he was patient.

“He wouldn’t criticize; he wasn’t loud and demonstrative. I mean, he wasn’t loud and demonstrative anyway, just in general, but especially not at the baseball games,” Randall said. He did, however, have two firm rules for his son: 1) Don’t golf if there’s a baseball game later that day; it’ll mess up his swing — though that rule was oft violated — and 2) Don’t watch strike three. Ever.

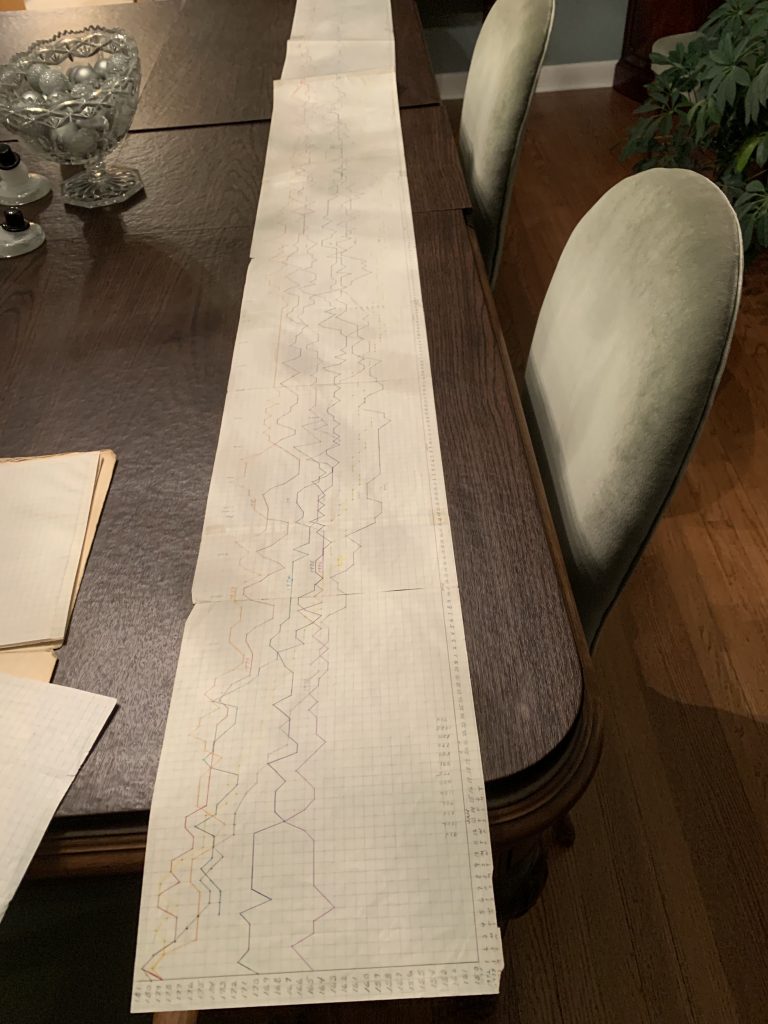

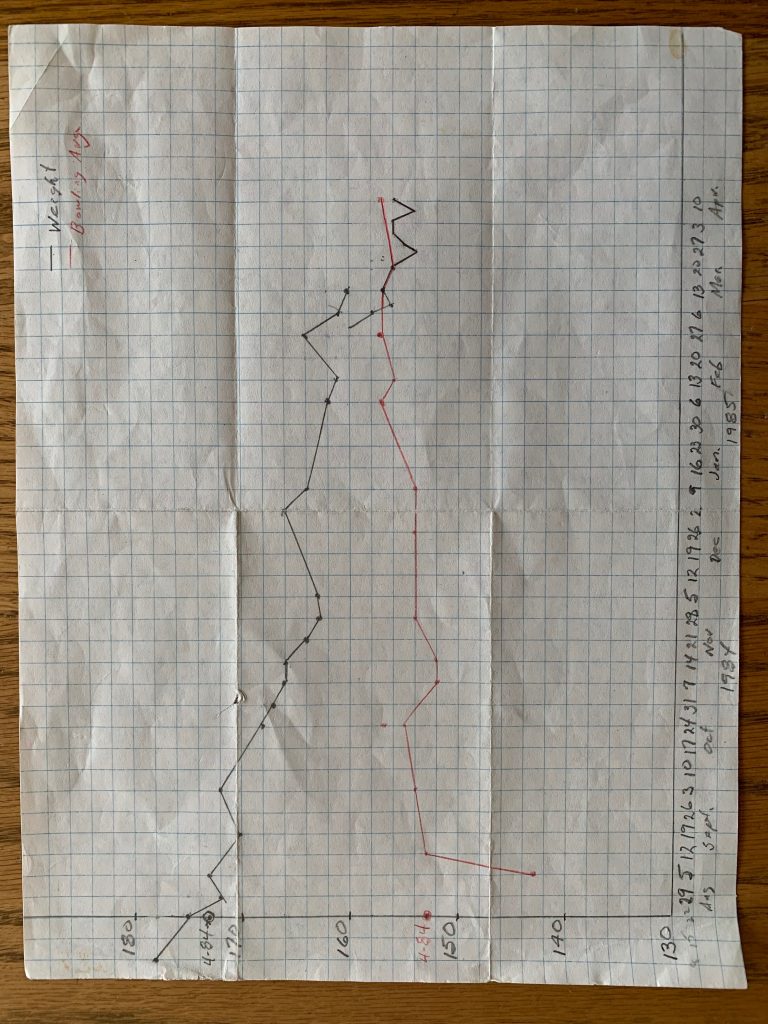

Ray wasn’t just meticulous and calculated as it pertained to Randall’s athletic exploits. He did his own taxes up until the very end. He taught Randall how to keep a scorebook at baseball games, a skill he had possessed since tracking the play-by-play of his recess games in grade school. He kept a graph, which extended longer than Witter’s dining room table, that tracked his weight every day for several years — and a separate graph with his weight against his bowling scores, hoping to keep the latter above the former. He carried a notebook which tabulated his daily spending, divided into categories such as “food,” “car” and — consistently the priciest — “wife.”

“I don’t know how he had time to do all that,” Klickna said.

He was clever, too. Klickna recalled an afternoon out on Lake Springfield where her dad — for whatever reason — wasn’t supposed to water ski, yet he did anyway. Evidence of his transgression came in the form of wet clothes, but Ackerman had a simple solution.

“We get back to the boat dock, and he — accidentally-on-purpose — as he’s pretending he’s hooking up the boat, falls in the water,” Klickna said. “Mom says, ‘What’s going on?’ And I think he finally said, ‘Yeah, I went skiing’ … He didn’t care.”

His wit and sharpness remained until his final breath. That stood out to everyone who knew him, including David Blanchette, a writer who interviewed the 100-year-old Ackerman for a State Journal-Register feature in 2018.

“The guy was a hoot. Sharp as a tack,” Blanchette said. “I knew he was 100 years old, and I had this image in my mind of, well, this is what 100-year-olds look and sound and act like. And he was none of those … He just seemed to be able to recall instantly names, dates and posts that he had made, people he had talked to, instances about games, what team was playing whom in the week to come and everything. And that’s just not something you see from a centenarian.”

Those aforementioned qualities came in handy every time Ackerman wrote a Sports Report.

Sports Reports — the subjects of Blanchette’s story — were emails in which Ackerman updated dozens of friends and family members on the latest happenings in the sports world, especially (but not exclusively) the Cubs and Illinois, making sure to inject his opinion where necessary, however harsh. There were 215 Sports Reports in total, spanning (with varying levels of consistency) from 2009 to 2018 — his age-91-through-100 seasons.

Inspired by a comment from fraternity brothers in 1990 that they never heard about Illinois athletics anymore, Sports Reports eventually became an outlet for Ackerman to mesh his wit and creative flair with his passion for sports. His trademark: intentionally misspelling the names of teams he disfavored. The St. Louis Cardinals were the “kardnulls,” the University of Michigan was “Mistch Again” — “mistch,” obviously, the word for manure when a young Ackerman worked on the family farm in Morton, Ill.

In his interview, Blanchette also uncovered another of Ackerman’s baseball-as-a-metaphor-for-life-isms: He opposed the idea of an electronic strike zone, insisting that “people need to learn from their mistakes.”

After initially receiving the story tip from Witter and approving it with his editor at the State Journal-Register, Blanchette sat down with Ackerman at his apartment, started his recorder, listened to a filter-less centenarian speak his mind for an hour and came to a realization.

“I contacted my editor,” Blanchette said. “I said, ‘This is gonna be longer than I thought it was gonna be.’”

The story, Telling it like it is, ran in the SJ-R on Jan. 18, 2018, all 1,433 words exactly as Blanchette submitted them.

“I just loved listening to his anecdotes … I just didn’t want him to stop,” Blanchette said. “I’m a freelancer, and I’ll do three- to four-hundred stories a year. And out of that I’ll probably truly enjoy about 50 of those stories. And I’ve gotta say that for 2018, that was one of the ones I enjoyed doing the most … To get paid for doing something like that, that’s a blessing.”

Allow me to break the fourth wall a little.

Ray was the first sports writer in the Ackerman family, but a grandson, yours truly, is following in his footsteps now. And as the lone non-Cubs-fan in the family (if you think Cubs fandom sucks, try the Phillies), I like to think this — sports writing — is our own unique commonality.

Don’t get me wrong: My humor never has and never will land like his did, though I’ll be damned if I haven’t tried. He successfully manipulates the English language itself for comedic effect, I write stupid dad jokes. There’s levels to this craft, and mine is lower.

Yet something about this story feels oddly timely, despite its focus being an event enjoyed more than five years ago by someone who died more than three years ago. This story here is the culmination of my higher learning experience, but in some ways, it feels like more of a beginning than an end. However many dad jokes I land from here on out, and however many (way more) of them flop, it’s somewhat grounding to know where the lineage began. I’ll always have that.

Alright, fourth wall back up.

That’s just one of countless examples of Ackerman’s legacy remaining across generations well after he said goodbye. Another: the fandom that brought a different grandson to Wrigleyville for that curse-breaking World Series Game 7 back in 2016.

“That was the reason I became a Cubs fan in the first place — was because I wanted Grandpa to see the Cubs win the World Series someday,” said Alex, Ray’s now-25-year-old grandson. “I don’t know how many things there are that are popular among 5-year-olds and popular among 95-year-olds. Sports, it bridges the generational gap, you could say. There’s something timeless about it. The feeling of when your team wins when you’re a kid — it kind of stays with you.”

To be brutally honest, Ray Ackerman the kid never quite knew what it felt like when his team won, because it seldom happened.

Maybe, when it finally did in 2016, his reaction was not just about the Cubs winning it all that year, but also about 98 years of unfamiliarity with baseball glory suddenly paying off.

“We were cheering and stomping on the floor,” Witter recalled of that night’s celebration. “It was like, ‘Oh my gosh, we’re creating a ruckus.’ He’s like, ‘I don’t care! I don’t care!’”

It was, in some sense, a race against the clock, and Ackerman had won.

He took his victory lap, too. When the Cubs toured the World Series trophy to the Illinois State Capitol in Springfield, each representative could invite two people into the gallery to see it brought out onto the floor.

Tim Butler, a state legislator and a friend of Witter’s, called to invite her and her dad.

“I was told this morning,” Butler announced to the crowd from the Capitol chamber that day, “he has his Cubs fan club card from 1928 in his wallet still. So, Ray, for you, we’re gonna bring you back next year when you’re 100 and do this all over again with another world title.”

Later, the trophy made its way down to the Secretary of State’s office on the first floor, and visitors lined up for the opportunity to touch it. Ackerman and Witter got in line early and struck up a conversation with the one woman ahead of them, who told them she’d grown up watching Cubs games with her late father and was there in his honor.

“And then she said to Dad, ‘You need to go in front of me in line because you should be the first person in this line to go in and touch the trophy,’” Witter said. “They were having this spiritual kind of experience, because it really was so much more than a win.”

And when the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum hosted an exhibit about the Cubs-Cardinals rivalry, and Ackerman showed off his die hard Cubs fan license, a representative from the Cubs’ administrative office even let him try on her World Series ring.

If the Cubs hadn’t come back from their 3-1 deficit against the Cleveland Indians (now the Cleveland Guardians) in 2016, if the World Series drought had reached 109 that year before turning 111 by the time he died, Ackerman’s life would have been no less fulfilling.

In fact, he probably wouldn’t even have dwelled on it all too much. That wasn’t him.

“He just took that ‘baseball is a series of failures’ as part of the way he went about what he did,’” Randall said. “He took [losing] as, ‘I really wanted them to win, but it didn’t work out, and we’ll try again the next day, and life goes on.’ It’s like, even though he was a passionate fan, I think he had it overall in perspective of life and the things that — I mean, you know. He fought in World War II. So, like, in comparison, he had that sense of it.”

But Ray had taken enough losing in stride over the course of his life. It was time to reap the rewards. It would have been cruel for him not to. And if you don’t believe in the baseball gods, 2016 should have you reconsidering.

The gods rewarded his patience, indeed. The day he died, Witter summed it up in an email on the Sports Report chain with one line in particular — a line that certainly applied to his Cubs fandom but which was appropriately meant to describe his life in general: Dad certainly didn’t leave the game early.

A couple years before he died, Ackerman celebrated his 99th birthday in a Concordia Village ballroom, where a near-century’s worth of anecdotes and Ray-isms coexisted with one outstanding question regarding longevity:

What’s his secret?

To the complete stranger who knew nothing about him but that aforementioned number, which presently carried two digits and would tack on a third the following January, it was a valid question.

To everyone else, though, including the entirety of that ballroom, it was rhetorical.

Ackerman answered it anyway.

“First, you gotta stay active and keep your sense of humor. And having a young wife that takes care of you for over 68 years is your number one thing.

“Then,” said Ray Ackerman, my grandpa, “I had to wait for the Cubs to get rid of the Billy Goat Curse and win the World Series!”