“We meditate on the three eyes of the Absolute

That permeates and nourishes everything like a sweet fragrance.

Just as the ripe cucumber is released from its bondage to the stem,

So may we be freed from death to dwell in immortality.”

Neel Iyer, an Indian American sophomore at USC, chanted his prayer in Sanskrit to the victims of the Atlanta shooting at a vigil. The event was co-organized by the USC Asian Pacific Islander Faculty and Staff Association, USC Office of Religious and Spiritual Life, and Asian Pacific American Student Services, in which more than a hundred people congregated together at USC Village to remember the victims of anti-Asian hate crimes, a year after the tragic event of Atlanta Spa Shooting.

On March 16, 2021, a shooting spree occurred at three spas or massage parlors in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia. Eight people, six of whom were Asian women, were killed in the string of deadly shootings. And this tragic event marked the climax of the exponential growth of anti-Asian hate crimes after the COVID-19 pandemic.

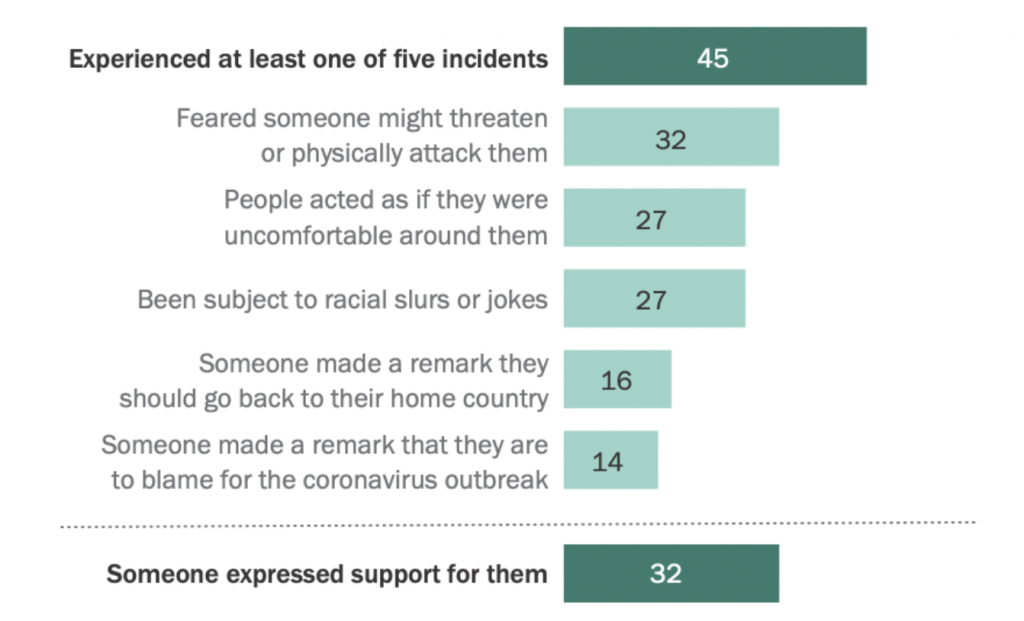

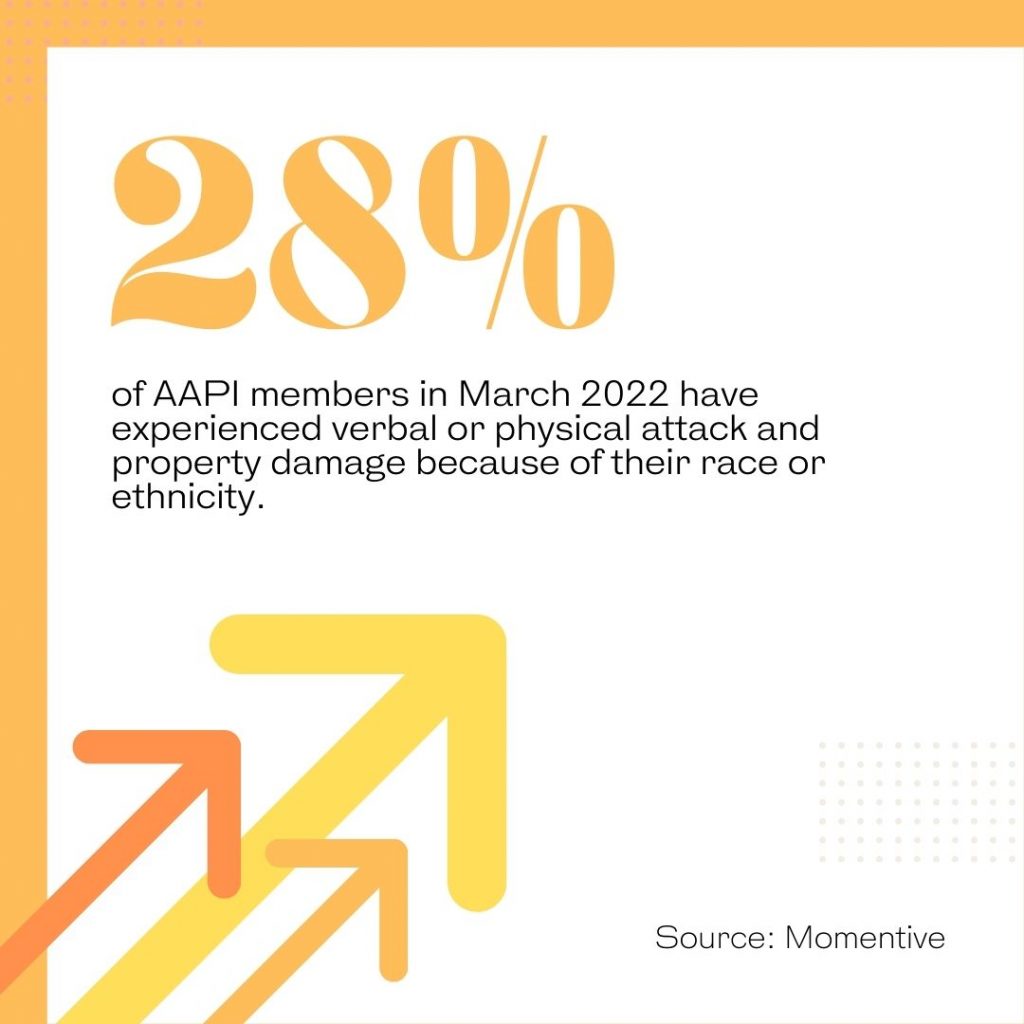

The rapid rise of hate crimes targeting Asians followed the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and then-president Trump’s rhetoric that falsely associated the COVID-19 pandemic with Asians. A Pew Research Center survey showed that 45% of Asian adults have experienced some form of hate crime. More specifically, another survey conducted by Momentive in March 2022 has indicated that at least 28% of AAPI members have experienced verbal or physical attacks and damage to properties specifically because of their race or ethnicity.

The existence of hate crimes against Asian Americans was not a peculiar product of the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, its history is rooted in a long history of anti-Asian racism in the United States, dating back to the first wave of Asian immigration to the United States in the 1800s. However, the Atlanta shooting was particularly perturbing to the Asian communities, especially women members within, because of the flagrant racism and misogyny indicated in the massacre.

“The Atlanta shooting was the was what we all feared the most, building up to all of the different hate crimes that had been happening since early 2020,” said May Lee, an award-winning TV anchor and the host of the podcast “May Lee Show,” the first pan-Asian talk show for women.

“He specifically targeted Asian businesses, and he specifically targeted Asian female,” Lee said. “And this was a modern-day example of how those negative stereotypes of Asian women still exist.”

Robert Aaron Long, the perpetrator of the shooting, said that he targeted these parlors to get rid of sexual temptation for himself and others, which, again, reflected the perennial hypersexualization and objectification of Asian women in the country, which incited further anxiety from Asian women.

“They weren’t even really talking about [the victim]. They focused on the shooter, saying that he was having a bad day,” Lee said. “That’s why it hit us so hard, especially Asian women. We were reminded that yet again, society doesn’t see us as whole. They don’t see us as fully human.”

Because of its peculiar severity and detrimental effects, the tragedy spurred a reckoning about hate crimes targetting at Asian communities and galvanized community members to build grassroots coalitions and political solidarities to raise awareness about the issue to provide victims with platforms to seek help and healing. Asian pain and unification permeated the public sphere on a national level simultaneously, for the first time in decades.

Vigils for the Eight Lives Taken in the Atlanta Shooting

Stunned by the Atlanta shooting, Linda Truong, managing director of USC Libraries’ information technology group, texted Grace Ryu, the associate director of the East Asian Studies Center at USC to establish a formal coalition for API employees at USC.

“After the Atlanta shootings, we were so upset, angry and frustrated,” Ryu said. “We didn’t have a forum where we could just kind of get together, and we’re all in our silos and just, you know, mad, angry and sad alone.”

Thus, in order to provide a safe space for all API faculties and staff to discuss what was happening and what should be done, the Asian Pacific Islander Faculty and Staff Association, or APIFSA, was established in April 2021, and more than 300 members joined the organization within a month.

“We mobilized very quickly and very organically,” Ryu said. “I started emailing colleagues, and quickly from that we had our first meeting, in which more than 90 people attended the meeting.”

Shortly after its first meeting, the association established six committees for distinctive AAPI-related issues in the local community. For instance, The Advocacy and Policy Committee was responsible for direct outreach to leaderships within the USC administration and faculty senate bodies; the Community Outreach and Relations Committee was in charge of building a wider USC community of API and other affinity groups to develop programming and partnership at USC.

“Not only is it an attempt to highlight the uniqueness of our own experience within the USC community, but also to bring us together and find commonalities with other groups across the campus,” Truong said.

Accordingly, on the anniversary of the Atlanta Spa Shooting, APIFSA organized a vigil, in collaboration with the Office of Religious and Spiritual Life and Asian Pacific American Student Services, to mark this memorable moment and honor the victims of anti-Asian hate crimes.

During the vigil, Vanessa Gomez Brake, the associate dean of Religious Life, delivered a prayer for passed victims of the Atlanta Shooting and other hate crimes.

“I wanted to express the outrage and the deep sadness that I have felt, for my own family has experienced anti-Asian violence,” Brake said.

In addition to articulating her sadness, Brake also channeled her grievance to her vision of a more inclusive future for marginalized groups, based on her observation of the younger generation of Asians in comparison to the experience of elder Asian Americans, like her mother.

Brake’s mother immigrated to the U.S. in 1975, during which she encountered unnumbered discrimination, but she, like many other first-generation immigrants in the past, did not choose to stand up against the rampant injustices.

“If you ask her about that, she will say, ‘that’s just the way things were,’” Brake said. “But now our generation and those younger than me are in a different place. They do not want to put up with the microaggressions, or the actual violence. We don’t want to put up with it anymore.”

Additionally, reflecting on the trauma brought by the Atlanta shooting, Brake believed that the vigil and countless initiatives made by community organizations is the most effective way to tackle the systemic racism and the obnoxious stereotype against Asian, especially Asian women.

“I have told people that change happens with our own hands,” Brake said. “I have seen a number of people who have been activated by the ongoing anti-Asian hates, and there are a ton of new initiatives that are reaching out to our communities around wellbeing, healing, or belonging.”

Social Organizations with Various Missions Came to Fight against Hate Crimes

Since the COVID-19 ravaged the world in early 2020, a multitude of Asian American social organizations with multifarious focuses have directed their attention to social justice issues brought by the anti-Asian hate. Asian American Christian Collaborative, a social coalition that was established to educate Asian Americans about the Christian faith has modified its mission to amplify the voices, issues, and histories of Asian Americans in the church and the larger society.

Raymond Chang, the president of the collaborative, believes that condemning and addressing anti-Asian hate issues is a natural move under the teachings of Christianity.

“We are all social creatures,” Chang said. “We thus cannot avoid social issues. We enter into life with Him and are called to participate in life with Him, which means that we extend His hands and feet into the pains and problems of the world.”

In its effort to raise people’s awareness about anti-Asian racism in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, AACC has endeavored to produce a rich media ecosystem, including social media, podcasts, magazines, and online events to have Asian Americans seek help and healing from the organization.

After the Atlanta shooting, Chang engaged in conversations with Atlanta-area pastors, from which he learned that some in Asian American Christian community in Atlanta wanted to facilitate a response.

As such, leaders in different cities reached out and agreed to facilitate a gathering at the same time as the Atlanta event.

The initiative developed rapidly in the course of a week. On March 28, 2021, at 4 pm EST, around 5,000 Asian American Christians and friends convened in 14 different cities across the country at the same time to mourn the eight lives taken in the Atlanta shooting, proclaiming against the anti-Asian racism that has spanned the centuries of history.

In the rally in Chicago, Jessica Min Chang, Chief Advancement and Partnerships officer at Wheaton College and Chang’s wife, expressed that “it is perhaps the first time we feel we’ve been allowed to be sad and angry about the anti-Asian racism we have endured throughout the centuries of Asian American history.”

On that day, as Asian Americans from various backgrounds organized, planned, convoked, shared, prayed, and sought unity, the rallies became a valuable space amid the surge of anti-Asian hate crimes as people could freely and safely express lament and seek solace.

“This was a new moment in the history of the Asian American church,” Chang said. “[That was] something I don’t think has ever been done before. And it was amazing to watch churches rise up to respond.”

Chang firmly believes that community-level organization and care is an essential route for Asian Americans to seek healing and growth against the “resurgence of anti-Asian racism.”

“Whether people believe in Jesus or not, I think one thing that people can rest on is that they are communal beings that were made to love and to be loved,” Chang said.

Establishing Feminist Collective Politics and Media

In December 2019, as massive cases of COVID-19 were detected in Wuhan, and the virus quickly plagued the entire world, Vivian Shaw, a professor in Asian American Studies at Vanderbilt University, noticed a wave of anti-Asian racism looming in the U.S. As such, Shaw founded the AAPI COVID-19 Project, which is a collective research project that explores multiple layers of harm connected to the pandemic—the virus itself and the intensification of racism and xenophobia.

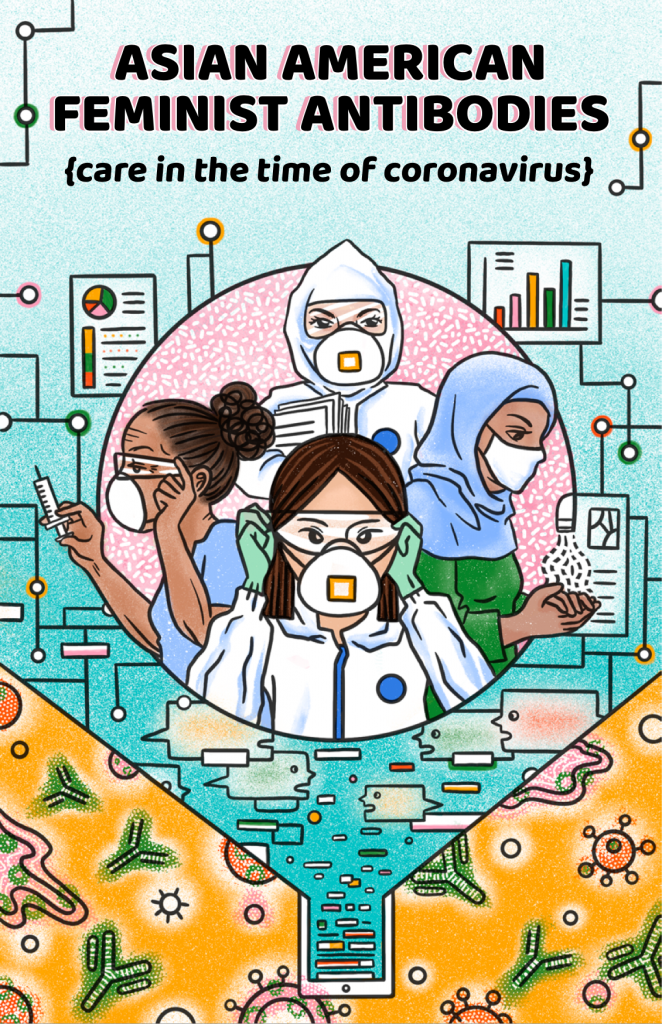

As part of the research, Shaw collaborated with her friends and colleagues at Asian American Feminist Collective, in which she contributed to the design and publishment of the zine Asian American Feminist Antibodies: Care in the Time of Coronavirus.

In the beginning, the editorial team drew primarily on their existing networks, reaching out to friends that whom they have previously worked alongside. Later, many poets, artists, and writers who heard about the zine quickly lend their work and perspectives to the zine.

As a result, through the effort of hundreds of AAPI community members, the zine features works contributed by a range of AAPI community members and perspectives, including healthcare workers, students, people living with chronic diseases, journalists, and community workers. It also incorporated contents from a spanning range of forms including poetry, essays, stories, visual art, and resource lists.

“The ways we touch, reach, make space, and connect reveal how we relate to those with whom we build community,” Shaw said when she reflected on her experience of making the zine.

Later, to generate further conversation from the zine and create additional space for dialogue around the topic, AAFC hosted an hour-long Tweetchat on community care in April 2020, using the hashtag #FeministAntibodies. According to Shaw’s research, the Tweetchat offers a specific discursive articulation of Asian American collective politics within a technocultural space as a way to intervene in and remediate the racialization of Asians during the pandemic.

Notably, Shaw concluded multiple themes that challenged dominant discourses around Asian American collective politics. The most important theme was the call for collectivity and interdependence.

Particularly, participants in the chat highlighted the urgent need for interdependence between individuals, families, and communities despite government neglect. Specifically, in the era of social and economic crisis, participants presented a feminist framework of interdependency and collective accountability to one another.

For instance, a disabled artist Matilda Sabal highlighted practices of interdependency to build intimacy across distance and isolation, as she described that “calling friends & comrades, coworking over Zoom, building space for rest and joy…the revolutionary work can be done anywhere, even your bed.”

Participants also acknowledged the feeling of being politically re-energized to mobilize with other people during this time.

Scholar and activist Kim Tran expressed the wish that people could “recommit to movement work…and focus on building people power, building with each other.”

The theme of interdependence also evinced the motivational effect of organizational work. “I think that community alternatives offer something and give you more options than relying on the police or certain types of administrative kind of resources that may take a long time or which people may become difficult to get eligibility for,” said Shaw.

Bar Associations Providing Free Legal Services and Toolkits

The National Asian Pacific American Bar Association is a national organization that represents the interests of more than 60, 000 Asian Pacific attorneys, law students, and judges around the country founded in the midst of the Civil Right Movement.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, NAPABA has leveraged its legal resources and national influence to help victims of anti-Asian hate crimes.

“As soon as the pandemic was sort of in full force, and we saw an uptick in hate crimes and bias incidents against members of our community, there was really an outpouring of support,” said Priya Purandare, the executive director of NAPABA.

As such, big corporations, including Apple and Walmart, and individuals reached out to NAPABA to discuss what can they do to help address the surge of hate crimes.

Having gathered copious resources and funds from corporations, affiliated organizations, and individuals, Purandare believed that the biggest challenge of NAPABA was “really figuring out, what can we build to help sustain a program where attorneys that might not have specialization in this field, and how can they make a difference.”

The first step that NAPABA took was that it resurrected its hate crime resource page. The page was established decades, as hate crimes targeting AAPI members have existed for centuries. This time, NAPABA led the charge that overhauled the web page, publishing videos calling for solidarity, inviting large corporations and law firms to make a pledge to address hate and bias, and collaborating with community-based social organizations at hundreds of localities to provide legal advice and services.

Moreover, NAPABA designed a hate crime report form, through which victims of hate crimes could report their experiences and procure legal help from attorneys at the association.

“If you’re a victim of a hate crime or a bias incident and you fill out a short form, then the pop up [will] refer you either to the alliance or to one of our local affiliates,” said Purandare. “We do evaluate every single one. We pride ourselves on responding to every single victim. because we know how difficult it is for members of our community to even talk about something like this.”

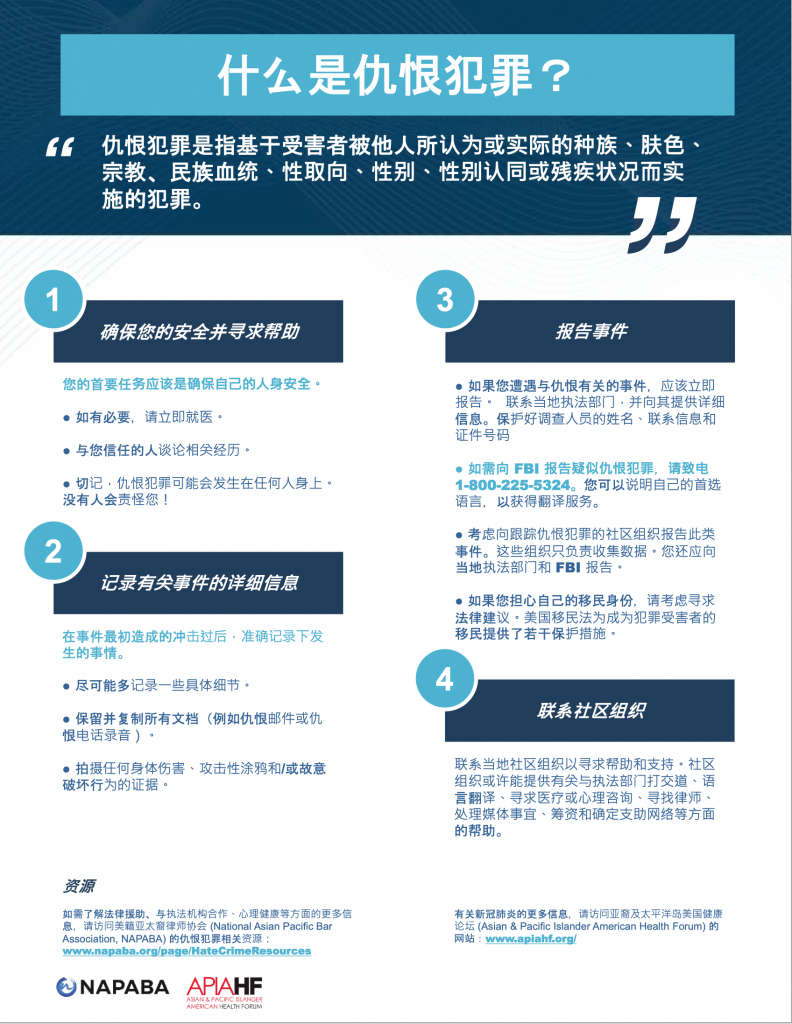

Moreover, NAPABA also developed toolkits in partnership with the Asian Pacific Islander Health Forum written in dozens of Asian languages that aimed to teach AAPI members how to report on hate crimes and the importance of vaccination.

“We’re providing information in an easily digestible, accessible way and obviously, having it in language is critically important,” Purandare said. “And we see that they’re effective, because it’s really hard to navigate this stuff and know what to do.”

According to Purandare, the toolkits have been distributed to thousands of Walmart stores, hospitals, and nursing homes in Asian immigrant neighborhoods. Moreover, those toolkits were even delivered to the Department of Justice and the White House when NAPABA was lobbying for policies that benefit Asian Americans.

Despite the unprecedented level of social collaboration and unionization, Asian Americans have not witnessed a decline in the hate crimes against them. The first three months of 2022 have already seen a long list of violent assaults against Asian Americans, including the death of Michelle Go, a 40-year-old Asian-American woman who was pushed to her death in front of a New York subway train.

However, without any doubt, the unparalleled robust unification of Asian members in society has become an effective source of healing and empowerment for many of them.

As the internalized invisibility and marginalization of the community keep its members extremely vulnerable, which allows media and the state to shape the Asian narrative with multifarious ill-minded narratives, including model minority myth and the China virus, members of social organization found organizations as a valuable platform to break out those narratives and voice their own opinions.

“But when people show up for each other and build trust, we disrupt that pattern. Ultimately, that is the best way to fight back against prejudice and violence,” said Julie Ae Kim, the founder of Asian American Feminist Collective.