To belong,

is to dance folklórico

For Chicanos who dance folklórico in the United States, folklórico has become part of our story.

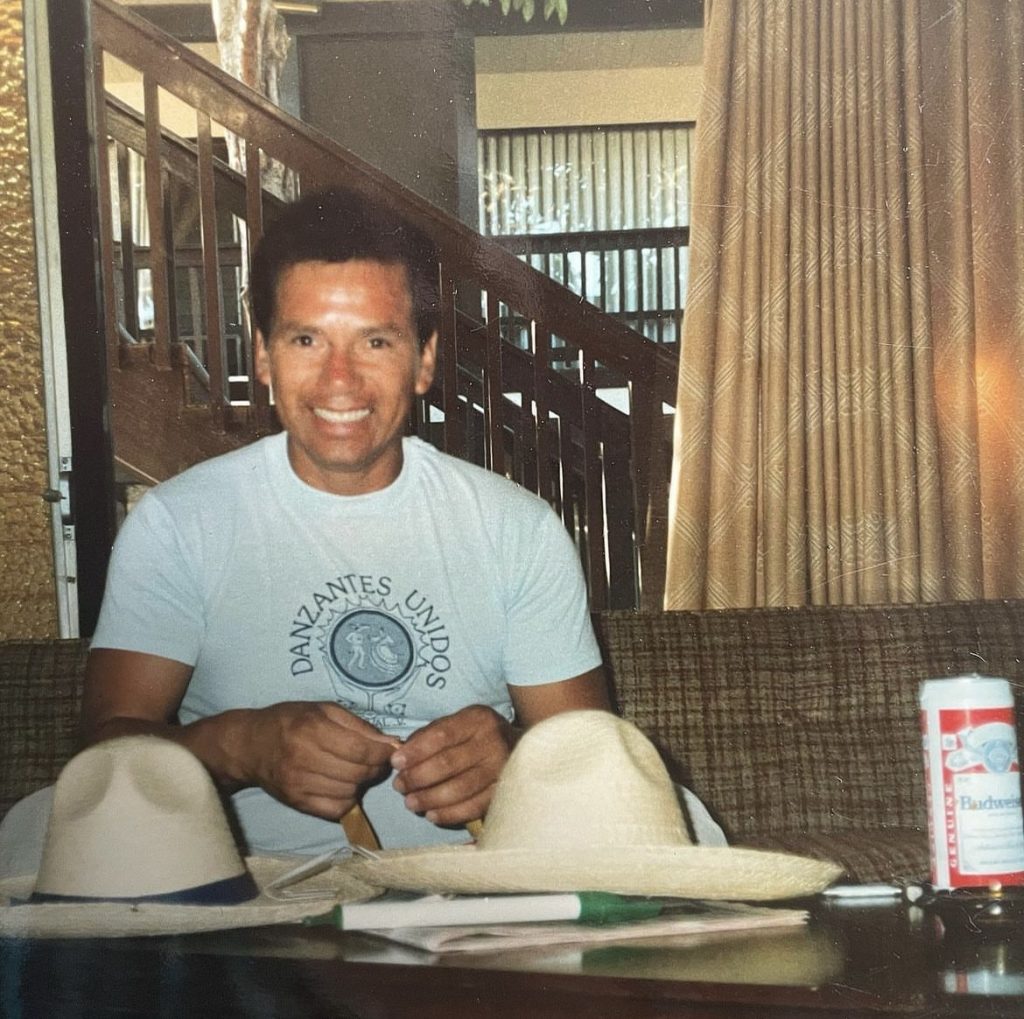

Photo Courtesy of Steven Tan

Dear Reader,

Since I began dancing folklórico at 18, I can’t imagine living without it.

Folklórico has given me a community, a home, and has become synonymous with my identity as Chicana.

But I am not the first.

Folklórico has touched many souls before me, some who I have been granted the privilege to speak with for this project.

They continue to live and breathe folklórico, after all these years.

This capstone is dedicated to them, and it’s a recognition of the significance folklórico still holds for Chicanos today.

Sincerely,

LeeAnna Villarreal

Folklórico dancer, Emily Hurtado, performing a dance from the Mexican state of Nayarit.

Folklórico, originating in Mexico, is a traditional style of dance that reflects the various regions of Mexico, each with their own set of costume-wear (vestuario), dance, and music. Influenced by both indigenous and European cultures, each performance tells a story about the daily lives and traditions of the region’s people.

When Ballet Folklórico de México, under Amalia Hernandez, toured the U.S. in the 60s, it gave way to the widespread movement of folklórico across California. At a time that coincided with the Chicano Movement, many Chicanos were inspired, and saw folklórico as an avenue to reconnect with their Mexican heritage.

“The pressures of assimilation were much stronger back then,” said Javier Sepúlveda Garibay, USC Performing Arts Librarian and folklórico dancer of 13 years. “It was like a radical thing to participate in the arts if it had to do with your culture.”

Groups emerged across the United States, in both university and community spaces, like Grupo Folklórico de Mizoc, a company that Maria Luisa Colmenarez, 63, and her sister created in 1975, just as they entered high school.