Wandering through the briny banks of Fisherman’s Wharf as circles of fishermen slapped sea bass across damp pavements and construction workers roused the desolate corners with their foreign jargon was most reminiscent of the morning street vendors and passerby my father was used to back in Shanghai. A couple districts over, my mother was unlocking the steel chains to a local hair salon where she would spend the rest of her day inhaling bleach fumes and people watch as blonde-haired blue-eyed strangers biked past on Market street. This was 1989 San Francisco, a year where their peers back home faced rapid changes as the ruling Communist Party threatened political freedom, leading up to the monumental and deadly protest now known as the Tiananmen Massacre. With only a small sum of money in their pockets, a healthy touch of naivety, and an overriding sense of ambition, my parents resettled in the promising Golden City and faced a reality that would forever alter their life trajectory.

This is an immigration story about struggle, sacrifice, resilience, family, and the American dream.

PRE-IMMIGRATION, 1984-1988

Before coming to the US, my father, Chongbin Zheng, had a prominent role as an art professor at China Academy of Art in Hangzhou. He taught there for four years after graduating in 1984 and was acclaimed as one of China’s preeminent young experimental ink painters. At the time, venturing out of the classic traditional art style was considered progressive and daring. It wasn’t common to see a young artist utilizing overtly Western and contemporary influences within their practice especially post Cultural Revolution, which had pervading effects on the socio-political culture, and made an indelible impression on the following generations of Chinese artists.

“My formative years were deeply engaged with classic Chinese art, but making that transition towards western contemporary art was most crucial, particularly in the mid 80’s… It was an eye-opening generational change that us young artists needed,” he said.

He has his father’s tall nose, his mother’s deep-set round eyes, and long curly locks, which certainly contributed to his all around nonconformist image. He mounted his first solo exhibition at the Shanghai Museum of Art in 1988 which received the attention from local TV news stations and prompted a fellowship offer at the San Francisco Art Institute for installation, performance, and conceptual art.

My mother, Sha Xu, studied Japanese at the Changchun Foreign Language Institution and continued to become a Japanese translator for government agencies. She traveled around the country hosting tourists, businesses, and political figures. She is petite with soft features, and had hair down to her hips. She was a dominant force and adept at every task set forth. Both of them made a considerable salary and established themselves early on in their careers. Needless to say, they essentially had everything they needed by their mid 20’s. Despite all of this, they craved something even greater. They yearned for fresh opportunities and the freedom that their current environment could not provide.

In addition, they were fearful of a potential repeat of history that instilled such pervasive and ingrained effects, censoring and uncompromising.

“Your grandparents went through the cultural revolution. That was a really scary time. Lots of people died. We were just scared another cultural revolution was going to start. Our parents didn’t want us to go through what they had gone through and we didn’t want our future children to grow up in that kind of an environment, so your father claimed this opportunity at SFAI and we agreed to leave China.”

Little did my mother know just how challenging the emigration process would turn out to be.

THE INITIAL MOVE, 1988-1990

My father was granted permission to leave first in 1988 due to his position as a future graduate student while my mother remained at home. Receiving skepticism from the government having worked for a sensitive foreign agency, she recalled one particular afternoon when she returned home to an account of sabotage, perhaps by a coworker. Someone had dumped hazardous waste on her front doorstep and around the perimeter of her home. Dealing with the legal matters prompted a several month-long investigation that exacerbated the difficulty of her situation and prolonged her time away from my father,

“I didn’t know how many years it would take for me to see her again. Especially after Tiananmen…” he hesitated for a moment, “… if something else really serious happened to her and she couldn’t leave, then I would’ve gone back,” he said.

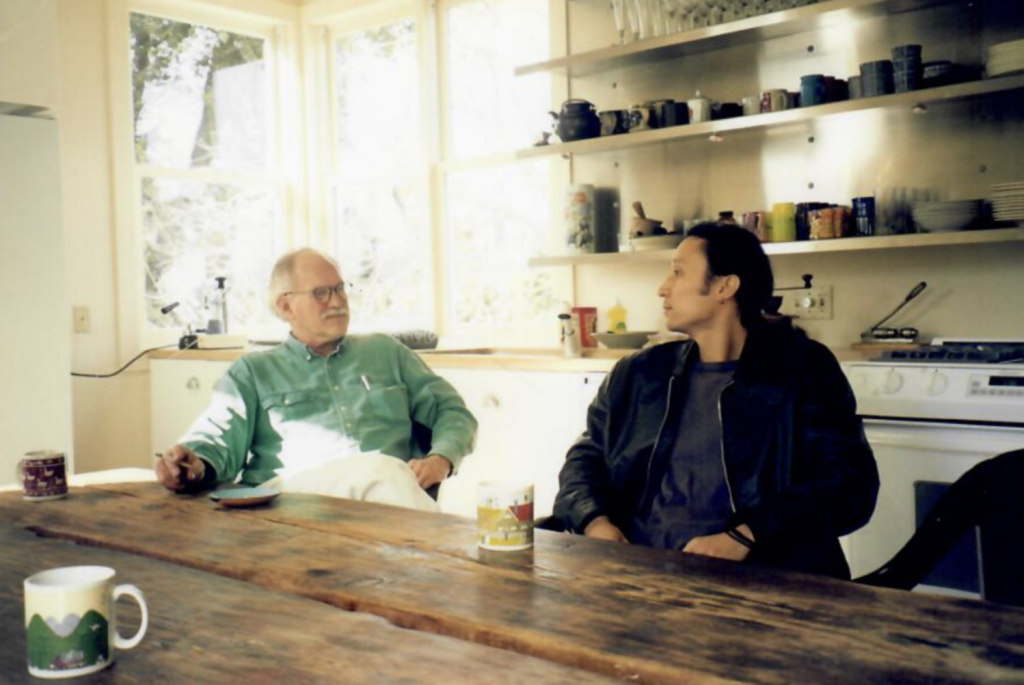

During that year, my father sought refuge at the home of a couple we now consider as family. Spaulding Taylor and Tony Manglicmot were merely strangers who generously offered their place to this young artist with nowhere else to go. They first met through a mutual friend in Hangzhou at the art academy in an underlit garage café. My father mentioned his dream of moving to California and they encouraged him without much thought, but to their surprise a couple years later they received an anonymous phone call.

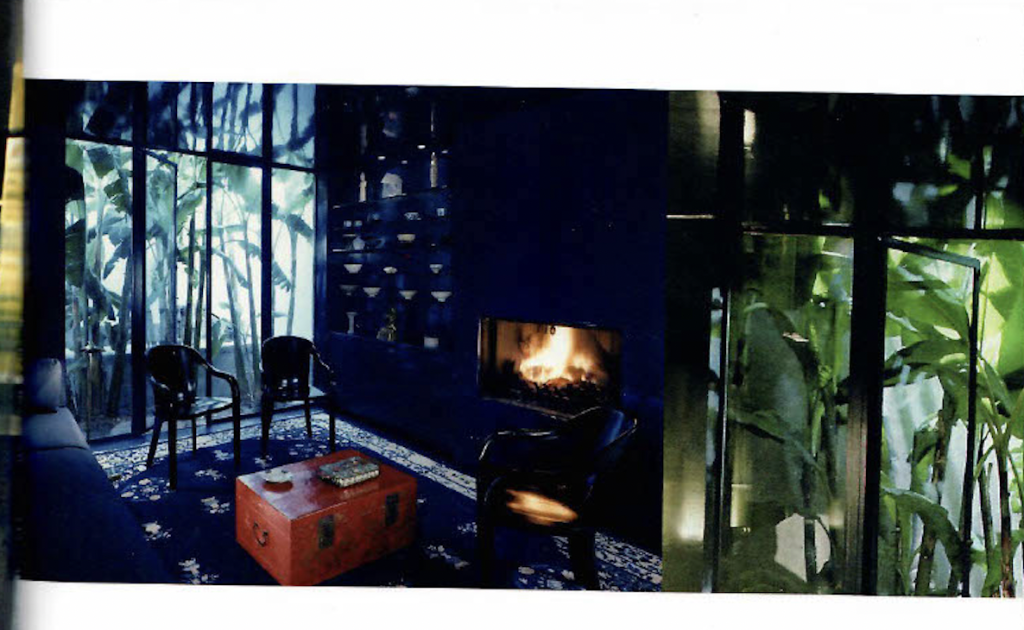

“I gave him a business card and said, ‘Let us know when you arrive.’ Next thing you know, there he was at Belcher street in the Castro. We had a guest room that was painted blue, and so he moved into the blue room. He called it his house,” Manglicmot said with a chuckle.

The couple reminisced on a handful of early memories with my father, but a highlight the three of them shared was the Muni incident.

“I lost myself. I lost myself,” my father repeated…

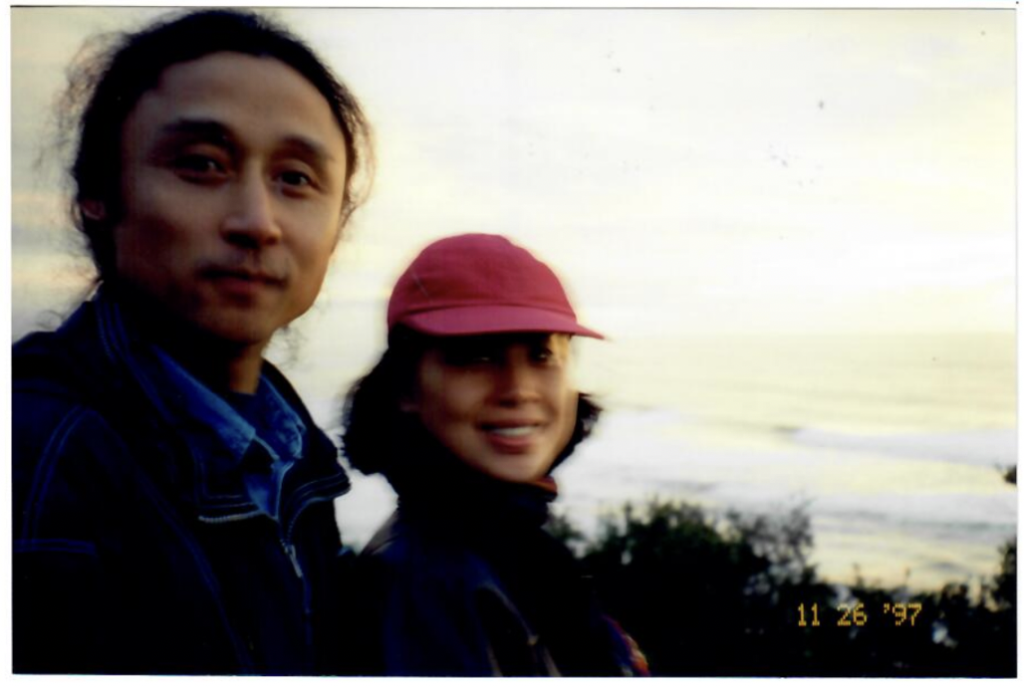

Being apart from his other half certainly contributed to his sense of disarray in addition to the initial shock of a foreign environment. It wasn’t until after the Tiananmen Square Massacre when President Bush signed the Executive Order 12711 that eased the immigration process when my mother could finally come to the U.S. and reunite with my father a year later.

EARLY WORKING EXPERIENCES, 1990-1993

Immediately upon arrival, she was hit with this anxiety.

“The biggest thing that was on our minds was, ‘We have to support our lives.’ We stayed at friends’ homes. Your dad needed a studio. How were we going to live? We made a total of $1000 a month – $500 for rent and $500 for food. That couldn’t sustain us.”

After a short period of working at a hair salon she transitioned into Japanese translation as it allowed her to speak a language she knew more often. In the meantime she also attended English classes generously funded by Taylor and devoted her time to honing on her third language skills.

“… She’s quite remarkable also in her own right because I mean she learned English very quickly… I think the reason she was able to learn so quickly was because she already spoke Japanese fluently so she had second languages,” Manglicmot said.

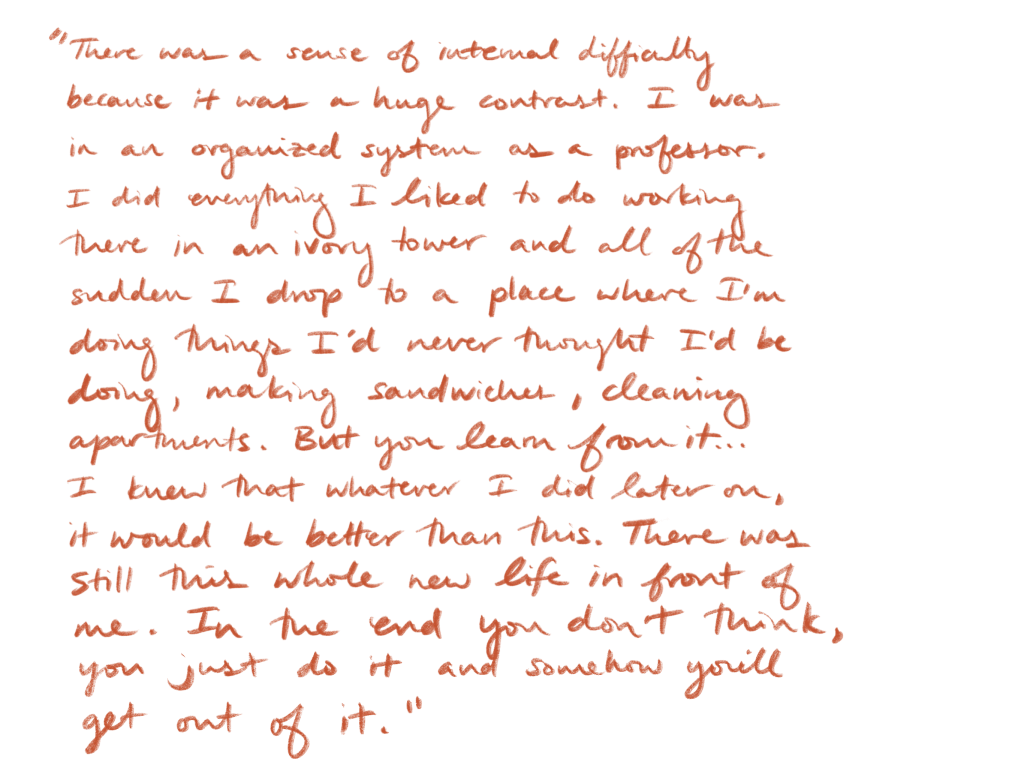

My father worked sporadically at several jobs alongside attending school for art and English. He delivered tourist photos for a small agency in Fisherman’s Wharf, made sandwiches at a shop owned by an older Vietnamese couple, installed for the exhibition department in the San Francisco International Airport, did set design for Berkeley Pacific Jewish Theater, Asian American Theater, Special Effects for Midland Productions and lastly, cleaned apartments. Endeavoring frequently exploitative experiences while having a very limited lexicon was a very isolating experience. There were moments that nearly pushed him past his limits both mentally and physically; however, despite these obstacles he saw the future as a green light ahead,

Soon enough after several years of diligent work here and there, my parents saved enough money to move into their own apartment on Market street.

RED AND GREEN COMPANY, 1993-2007

In 1993, my father finally went back to visit Shanghai and say hello to family. Filled with anticipation for the long-awaited reunion, there was nothing as joyful as finally seeing his mother.

“My mom said sometimes she’d see someone on the street who looked like me and would instinctively reach out wanting to touch the back of their head,” he said teary eyed.

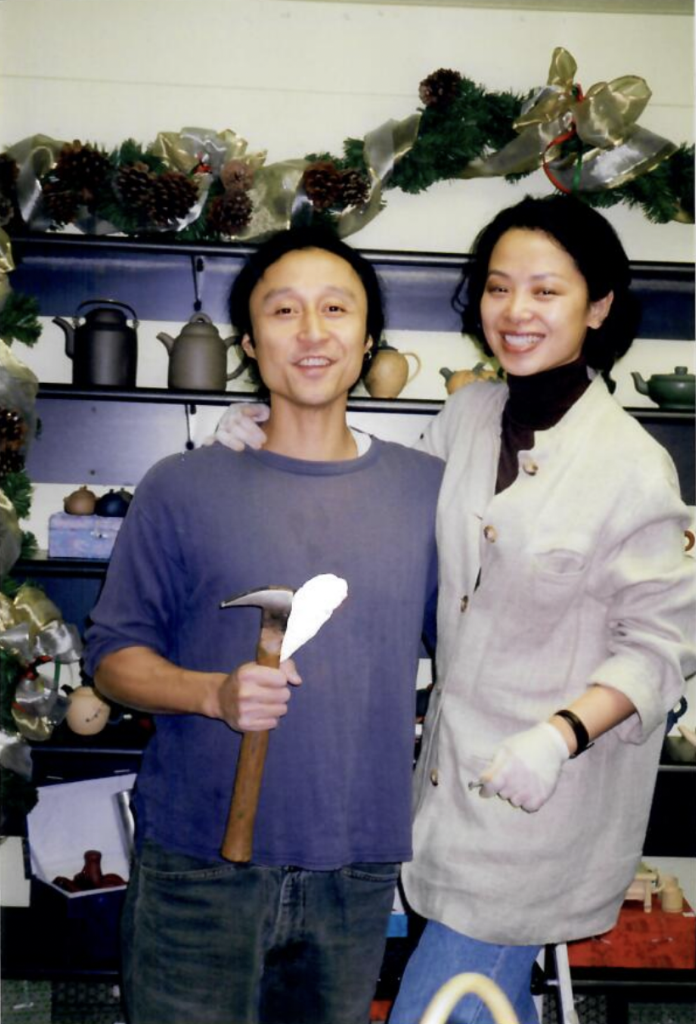

He had never imagined going back home so soon despite several years already passing. One day his friends took him to Yixing, a famous clay town that specializes in teapots. After browsing around the area for a day his friend suggested that he sell teapots, artisanal and authentically made from China. He came home with 50 pots.

With no previous background in business and marketing, my mother was absolutely shocked by the proposition, but something about a new change of pace sounded enticing. She had already been working as a translator for a while, so during her free time she quickly learned how to do accounting. And as an artist, one must be their own advocate and businessman with an eye for visuals and design as well, so by the time they were ready to move onto the next, they felt confident enough in their capabilities as a team.

“We started doing trade shows at the Moscone center; it was an instant success. Your father designed the booth in the most economical way, basic but good. We had no idea how to price them. But we got over $10,000 of orders. So we saw the light in this opportunity,” she said. So began the Red and Green company.

They learned everything from scratch, from how to import and export to the official set up of a company, advertising, how to price and catalog. My father drew each pot and designed the labels and the packaging. To him it was like an art form. My mother quit her job as a translator and started working full time on Red and Green. They communicated with customers who were initially locals, and throughout the years expanded nationally doing trade shows in Atlanta, Chicago, Minneapolis and New York just to name a few cities. Red and Green company’s pots found their way into major storefronts like Neiman Marcus, Dean and Deluca and smaller craft stores that sold internationally. Additionally, having to deal with clients and communicating with people around the country really helped propel their growth in terms of understanding American culture and society.

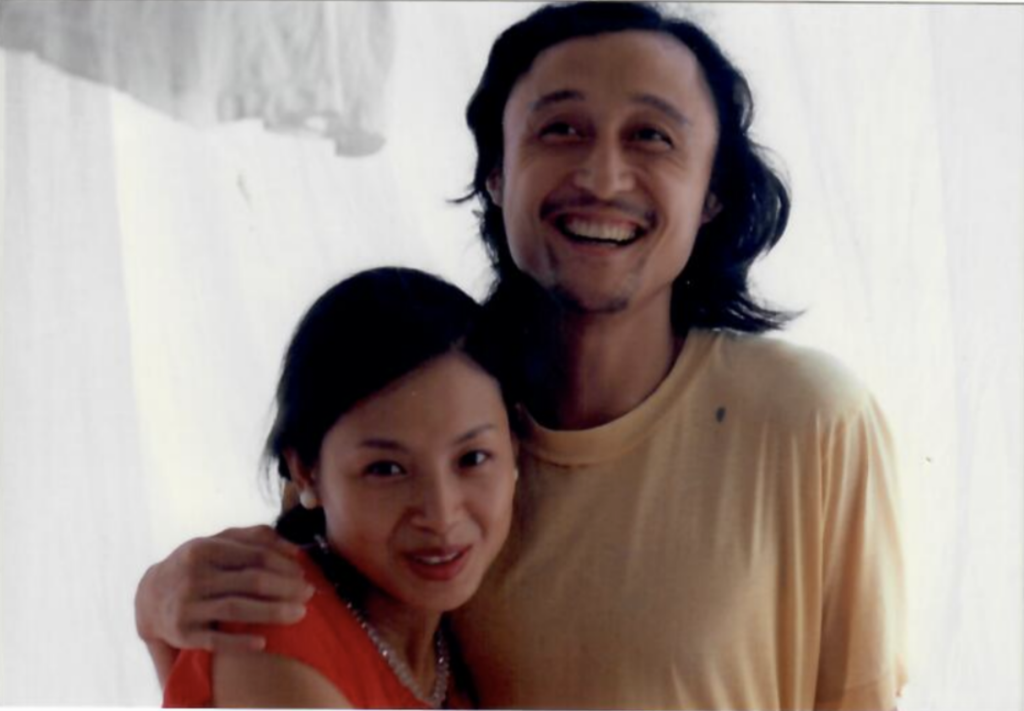

Throughout this time my parents were able to pay back Manglicmot and Taylor the share of what they owed for their hospitality, they moved to several locations around the area, finally landing in Marin County just north of the city, and they started a family in 2001. During all this change, one thing stayed consistent. My father always kept a place in the back of their South Market warehouse where he never stopped painting.

ART BOOM, 2007 – Onwards

Red and Green’s success built up to a foundation beyond what my parents could ever imagine, but along with that came some long hours, weeks of little sleep, overall tolls on health, and the major decisions that would determine the company’s future,

“We had to face the next steps. Either we stay at a small scale like a mom and pop shop or we expand the business,” my mother said.

My father expressed his fear that if they had stuck with the tea business for too long, he would end up making a lifelong commitment to this shadow career and grow further apart from his true passion.

“He had greater ambitions. I mean it’s part of the reason why we moved to America in the first place. Both him and I were not willing to give that up just yet and I was going to be there to support him every step of the way. Unconditionally.”

It was my grandfather’s 80th birthday in 2007. We were all celebrating with extended family back in Shanghai when my father got a call. I vaguely recall the moment, more so his beaming smile, and the palpable adrenaline in the room. The call was from Moshie Safdie himself, the Israeli-Canadian-American architect, urban planner, educator, theorist, and author who’s next project was the Marina Bay Sands resort in Singapore. He had been chosen for the largest public art funding project by the Sand corporation. He would compose 83 large-scale sized glazed stoneware ceramic vessels, each measuring three meters tall, holding trees within and along the outskirts of the building.

“I think it was because I was working with clay throughout Red and Green that propelled me into this first major project,” he said.

The project took three years to complete. While my parents’ business continued, mostly managed by my mother during this time, they agreed to dissolve the company in 2010 at last.

“For most people, Red and Green would be the success of their life… But at the height of that, your father decides, really all of a sudden, ‘Well, I’m going to go back to being an artist.’ I’m thinking, you can give up your very successful business and become an artist where most people starve to death,” Manglicmot said.

“But then within a very short period of time, he was able to apply the energy and the focus of what he had put into Red and Green into being an artist, and you know, that’s the magic of your father is that he does it so naturally.”

Both my mother and father are the epitome of the successful American dream. What I think is the reason why they were so successful is that no one ever told them that the American dream is in fact a dream. The vast majority of people only hope to achieve the potential they can reach by coming to America. Because they didn’t have that barrier, knowing that a dream is a somewhat intangible thing one can never quite reach, and because they believed in each other, they were capable of achieving success with every single thing they set their minds to. For passion, for the self, for family, and for love, they were able to make it all come true.

With a sigh of relief my father said,