Scuba Diving

Entering college as an environmental studies major in 2021, Emerson Damiano knew that she was interested in ‘ocean-related things,’ but not to the extent of what she would soon experience.

Shortly into her first semester at USC, her professor David Ginsburg, one of the heads of the Environmental Studies program, reached out to Damiano about potentially enrolling in his scientific diving class for the spring semester.

As a self-proclaimed “naturally anxious person,” the thought whisked her to a state of fear.

However, with steady encouragement from Ginsburg and a pact with a fellow ocean-enthusiast friend, she took the first step of her scuba diving journey – a decision that would eventually change her life.

During finals week at the end of the semester, she acquired her scuba certification – a prerequisite required to take the upcoming class.

The certification came with hesitation, as Damiano spent her pool training sessions tentatively deciding if she wanted to continue with the course. Once exposed to the ocean dives, though, her decision was made.

The turning point wasn’t the views, nor the few fish visible in the depths of Redondo Beach’s body of water – but the euphoric sense of peace she felt.

“Doing an extreme sport, as you call it, is kind of funny for me because I would normally avoid those like the plague. But when I’m scuba diving, it gives me the biggest sense of peace I could find.”

This was only the beginning, though. Following the open-water SCUBA certification, she began to prepare for the scientific dive course by passing the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (AAUS) dive physical.

In the spring semester of 2022, she began her course and the rigorous process of receiving the AAUS certification, which according to USC’s Wrigley Institute is the “prerequisite for advanced research in marine biology, oceanography, and many other ocean-related fields.”

Nearly two years later, she has scuba-dived ~120 times and is two certificates away from becoming a professional diver.

The underrated sport of scuba diving requires immense control and gear to be a successful diver. The reliance on an air tank and principal scuba techniques needed to avoid life-threatening situations, like barotrauma (failure to equalize ears), decompression sickness (resurfacing too quickly, and nitrogen narcosis (the feeling of drunkness or giddiness at deep levels), rightfully classifies it as an extreme sport.

For Emerson, though, these risks don’t source her anxious side.

“I think the reason why I feel so at peace while I’m diving, a situation that maybe one would describe as very risky, is that I have the complete power to protect my safety. I’m the one controlling my breathing; I’m the one controlling my buoyancy; I’m the one controlling all my equipment and checking it and putting it together.”

She continued by describing her experiences as a “forced meditation,” similarly relating her feelings to the psychology term, “flow state”.

The balance of improving well-being and passion towards a career focused on the environment differs from many extreme sports advocates. Damiano’s scientific diving course, Maymester at the USC Wrigley Institute in Catalina Island, and other dives have been spent researching species like eelgrass, a form of seagrass.

“ It’s a really big photosynthesizer, so it increases the amount of oxygen […] and because of climate change and increasing ocean acidification, it has started to decrease in population size.”

Eelgrass, according to Damiano is a keystone species that serves as a habitat for many fish species and could potentially be a natural filtration for harmful bacteria that are found at the beach or in the ocean.

Her environmental research and joy of scuba diving have inspired her to pursue a career with an environmental non-governmental organization (NGO), and hopefully, one day conduct her own diving research that can help push the government to make more environmentally protective legislations.

Unique and passion-fueled, Damiano’s story signifies how extreme sports is more than what a fellow bystander may witness – but rather provides encouraging fuel for all those who find the purpose within it.

Bungee Jumping

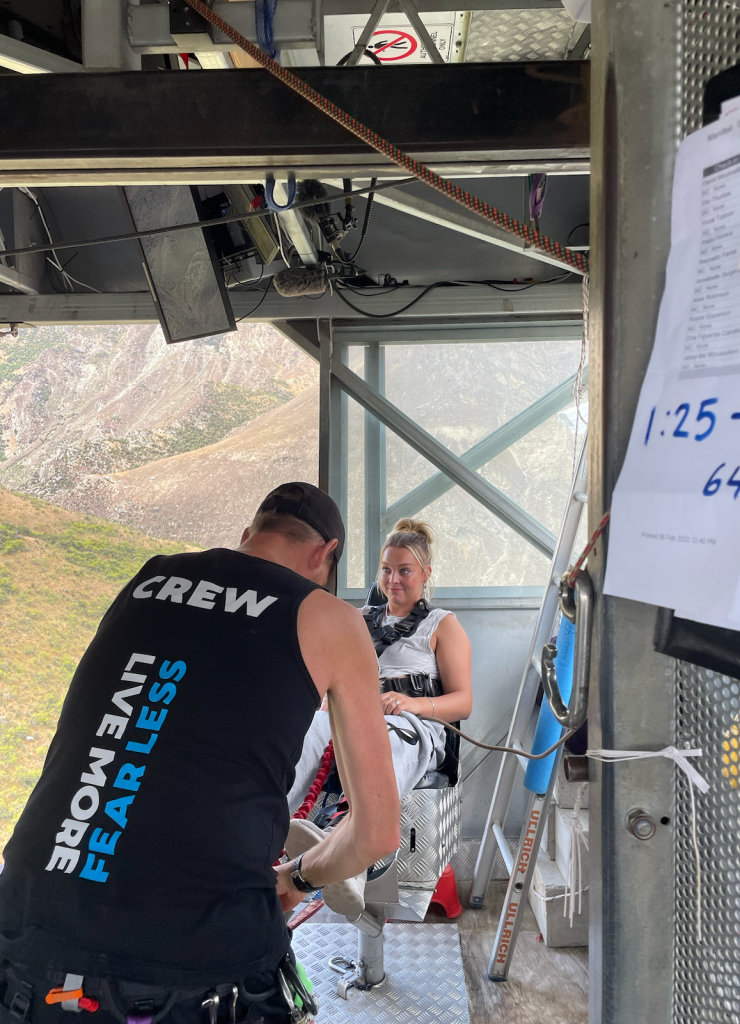

Plunging at your own will is not something that many people voluntarily do. As Bella Durgin-Johnson says, “there’s a time and a place for everything.”

Her choice to bungee jump at the Nevis Jump in Queenstown, New Zealand was a spur-of-the-moment decision – yet one that was well worth it.

Despite her fear of heights, Durgin-Johnson put her faith in an elastic bungee cord as she leaped 134m (roughly 439.6ft) south. Aside from her shrieks while falling, she explained the smooth experience between harnessing up and putting two feet back on the floating surface.

“In retrospect, it wasn’t bad at all. I think the most terrifying thing is that you are the one in control of that jump. So, I had to convince myself to put myself in a ‘life-threatening situation’ and jump because they can’t just push you.”

Like many others, Durgin-Johnson was enrobed with the attraction of shock tourism, a term about the tourism industry that dedicates itself to participating in dangerous activities and traveling to dangerous places.

Although bungee jumping was a spur-of-the-moment decision, she explained her satisfaction and security with jumping once.

“I think it was a cool experience – it made me feel like I can do anything, really; But, I don’t know if I see myself doing it again. I’d recommend it to anyone though. It’s nothing like I expected.”

Adrenaline also played a role in her jump. She described the fast fall and stomach drop as ‘thrilling tied with terrifying.”

Her motives, though slim, have proved that despite a fear of heights, an acceptance of danger, and an impulsive decision, the experience was well worth it.

Downhill Skateboarding

At age 12, Nick Broms started to downhill skateboard. The San Diego native grew up surfing but became fascinated with the sport thanks to his older brother and the inconsistent waves.

“The reliability of being able to go [skateboarding] is so much higher than surfing because there is always a street to skateboard on, and a lot of times there’s not good waves to surf.”

In the last ten years, his passion has driven him towards an exceptional career in downhill skateboarding. Soon after he learned, Broms began competing in San Diego amateur league races from 2014-2017. Although it took him nearly two years to place, his resilience paid off, and his career in skateboarding had a turning point.

Around 2016-2017, Broms competed in an outlaw race [illegally blocking a road] in Mount Shasta. The course was extremely technical, with many tactical corners that required skill and speed. The hill was super reliant on cornering ability (enterting or exiting a corner while maintaining as much speed possible), something Broms excelled in. His success in the race rapidly increased his passion into much more than a 14-year-old could imagine.

In the following week, Broms received four emails about competing again and gathered four sponsors. From there, he was granted a travel budget and spent the summer in Europe competing to get on the World Tour, and even more so, win the the Junior World Title.

He accomplished that and did it once more to title himself as the back-to-back 2018 and 2019 Jr. World Champion.

With a sport like downhill skating where speeds casually range from 50-80mph, a reward like a 2x title holder comes with the acceptance of risk.

However, Broms explains that although he acknowledges the treachery he may face – it rarely comes to mind.

“From my personal side, I don’t really see it. I understand that it’s really dangerous – but it’s not like I’m going out and trying to get hurt. Once you kind of get to the point where you understand risks, and you know how to stop effectively it becomes like riding a bike.”

He does put forth protective measures to ensure his well-being, though. A downhill skater like Nick wears a helmet, gloves with polyurethane pucks attached to the palms [to serve as a third point of contact], and on race days a full leather suit.

There’s no question that the majority of people cannot downhill skateboard – but for those who wonder what that feeling of racing at fast speeds may feel like, Broms explained it in two ways:

- To those who surf – “ It feels like when you’re riding alongside the face of the wave and really pumping down the line”

- Otherwise, “it isn’t anything crazy. We don’t have stomach drops unless you’re going over a hump in the road, but you definitely get some adrenaline because you’re not used to it.”

For Nick though, the repetitive nature of skating has eased his adrenaline highs to a natural flow state of mind. The adaption to the speed and environment has ‘rewired’ his brain to not react to any situation that isn’t life-threatening and keep a level head.

“[Downhill skating] is definitely meditative. My mind’s always going a million miles a minute and the only things that effectively calm me down are downhill skateboarding and surfing. The cognitive mental benefits and the community surrounding is why I still love it to this day.”

At only 21, there is a lot of life ahead for the already successful Broms. As he studies at the University of Santa Barbara and nears the end of his college path, it is only fair to ask if downhill skateboarding will remain in its same glory in the coming years.

Level-headed and future-oriented, the answer was mature and quite simple. With his new documentary, Nick Broms: What’s the Rush under his belt, staggering achievements and a unique journey that few can relate to, Nick acknowledges his path and respects his future. He plans to earn his degree and gravitate towards a “real job” for a few years. Then, he will take a year to prepare, compete, and travel the world to hopefully earn the Open World Title.

“I want to get that world title so that my mind can truly be at peace.”

-Nick Broms, 2024

Surfing

Family has played a significant role in Lorenzo Villela’s surfing career. As a toddler, he became obsessed with the VHS surf movies his family would play and soon got to experience his infatuation firsthand. Lorenzo recalls that he experienced his first surf session with his dad when he was still in diapers.

His obsession with the sport only grew. By middle school, surfing had become his main sport. Soon after that decision, a trip to the North Shore in Oahu, Hawaii, changed his perspective even further – inspiring him to explore the world of big wave surfing. It was there he discovered the mesmerizing 40-foot sets his uncles and other guys were charging. The sets were nothing like he had ever seen, requiring specialized boards and patrol to ensure safety.

“I found it really fascinating, and just wanted to chase that experience and see what it feels like.”

As life progressed, Villela spent much of it surfing. He participated in numerous competitions, learned tricky maneuvers, and ultimately chased the feeling he so desired. Lorenzo emphasizes that his consistency and practice led him to be successful in big-wave surfing.

“The biggest thing is skill; it’s all experience-based to get better in big waves. It’s not like small waves where it’s trick progression…the better you get, not only physically better but the safety techniques, breath holding, all help.”

Big wave surfing is no joke. From far away, it may seem potentially attainable; however, the repercussions of a wipeout can cause serious injury. To avoid this, Lorenzo has accomplished and advised that people know the measures of what to do when someone gets injured or knocked out from these types of waves. His suggestions include taking lifeguard courses, training with others, practicing reviving people, learning CPR and AED, wound packing, and first aid. While traveling, he also had the opportunity to learn and assist a docotr in sewing a foot together after a surfing injury.

Daunting but thrilling, Lorenzo emphasized that “it’s your safety level that brings you to progress in the water, not so much the skill level.”

The ocean evidently plays a significant role in his life. Aside from surfing, Lorenzo participates in free diving classes and dedicates his career to the environment. He studied marine science at the University of Hawaii and is currently a research technician who does coral reef ecology work and environmental consulting. The influence of surfing has noticeably coincided with his career.

“You’re always in a learning phase, so whether its university work, learning a new wave, how the ocean works, or it’s equally learning about a new species of coral that you didn’t know previously, figuring out new techniques and methodology with science, I think it’s very interconnected.”

To learn is to grow, and although Lorenzo is uncertain about pursuing a big wave surfing career – partially due to his belief that the industry is, unfortunately, oversaturated – surfing is something that he will always do for the love and not for the notice.

“I’m always going to do a passion, a lifestyle, and honestly for my mental health, because there’s no better rush than making the wave of your life. It takes you back to that feeling of what it was like when you got your first wave ever. Most people, most surfers will cap it at six feet or so, but they always forget to progress after.

Skydiving

Nick Prestine made a PowerPoint presentation to convince his parents that he wouldn’t die while skydiving. As a self-proclaimed “bucket list guy,” he had always wanted to skydive. The summer of his freshman year of college, he finally had his opportunity. Upon landing, his instructor asked him if he would ever jump again. The simple question brushed past him, but little did he know his answer would evolve into so much more.

After almost a year, Prestine found his way back to skydiving. His second jump alongside friends catalyzed his newfound hobby. Just two weeks later he began his first jump course.

“I got really addicted, really fast.”

One week led to the next, as Prestine spent weekends and eventually school days to acquire his first license.

“It’s a surreal feeling to fly through the air when you’re attached to someone, but I was like, what would this be like if I was just doing it by myself? And it turned out to be way sicker than I could have thought. It feels like a zero-gravity environment.”

His addiction has helped him climb the ladder of skydiving accolades and experiences over the last two years. Some of his accomplishments include:

A license: The first license you receive when you jump. Requirements include six hours of ground training and 25 jumps. Jumps 1-4 have two instructors assisting the trainee while solo jumping. They are there to pull the parachute or fix any malfunctions if the trainee forgets. Jumps 4-8 allow the trainee to jump with only one instructor. Jumps 8-16 are solo jumps. Jump 16 is graded.

B license: Attainable once 25 jumps have been completed. Includes a water-landing training class, at least 10 accuracy jumps, skills in advanced canopy control, and a quiz. This license allows skydivers to do night jumps, helicopter jumps, and hot-air balloon jumps.

Night-skydiving: Prestine insinuated a one-and-done mindset after his plummet in the pitch black. Unlike other dives, night dives require a flashlight.

“I don’t know if I’ll be doing that one again because it’s literally pitch black, you cannot see anything and you can’t see the other people that are in the air. But it was definitely a crazy experience, and I did it. I got another bucket list item.”

Hot-air balloon jumps: Unlike jumping from airplanes, divers can anticipate a classic stomach drop upon freefalling off a steady hot-air balloon. Its lack of relative wind allows for a weightless drop and initially quiet fall.

The eclectic skydive opportunities have exposed Prestine to just the brim of what professionals and those before him experience. Although everyone has a different reason for their purpose, Nick has described his love for soaring out of the sky as twofold.

“I think one, it’s a super cool experience with nature and great views. You can fly around like a superhero or be like a fighter jet, and do all these fun adrenaline activities. But then there’s the fact that it’s dangerous. You have to lock in when you’re doing it. My mind is chattering all the time. When I jump out of the plane it goes completely silent – you cannot have any side thoughts; That peace brings a level of relaxation that I do not get anywhere else in life.”

The unusual sense of peace provides Prestine with his why. While balancing college with his hobby, he credits the stressful life with his unique form of meditation: skydiving. Though as that ship sails and he moves towards adulthood, Prestine must consider how much that escape matters – and how skydiving will live in his future.

Prestine all smiles post jump

“I do have dreams. I think the coolest summer job would be being a tandem instructor, but you need three years in the sport and a lot of experience and money. It’s not realistic for me to do anytime soon, so it will definitely end up being a hobby. I would like to compete on a casual level and I’ve already got to compete in a few competitions too.”

Skydiving and meditation seem like an unexpected combination. However, many extreme sports athletes can attest to what people know as the flow state – a psychological mental state when a person is fully immersed in the task at hand. While in flow, time and self-consciousness are generally lost and replaced with an energized focus.

With risk comes reward

All of the prior stories have conveyed different reasons for participating in the extremities of their sports. However, is there a general reason for what draws people to extreme adventure?

Behavioral psychologist, Eric Brymer, has studied the psychology of adventure experiences and performance in extreme environments. As a guest on Episode 254 of the American Psychological Association podcast, Brymer explains the contrast in people’s notions.

“The traditional notion is the no fear, risk-taking, death wish notion – They’ve got the personality that drives them to look at these activities. Actually, the reason people start is as varied as there are people.”

Brymer continues this concept by explaining that some of his subjects got into their sport because of their families. Others explained that they ‘didn’t think they had any interest in any of this.

His research coincides with the purpose of these profiles – People do what they do because they can; They do it because they were influenced; They continue to do it because they are dedicated.

Extreme sports take a lot of commitment and hard work – which is also why people quickly discover that it’s not as easy as it may seem from the screen. It requires training, discipline, and accepting the possibility of severe accidents and sometimes even death.

However, people continously go back to these extreme sports. What is remarkable about the action-fueled activities is the different drives they bring to people. It often is not about winning, but rather gaining an experience, or feeling good about oneself. It’s evidently influenced careers, futures and helped people discover traits about theirselves they may not of known.

So, why do people do what they do? That truly is up to you.

- Photo & Video Credits:

- Skydiving – Photos/videos provided by Nick Prestine, @nprestine/Instagram

- Surfing – Photos/ @wsc_lorenzo/Instagram, Videos: SlawTV/Youtube

- Scuba Diving – Photos/videos provided by Emerson Damiano

- Bungee Jumping – Photos/videos provided by Bella Durgin-Johnson

- Downhill Skating – Photos/Videos @nick_broms/Instagram, Nick Broms/Youtube