Weight Loss Drugs in Teens: What’s the Real Cost?

Wegovy, Ozempic and other GLP-1 medications are more than just a fad diet for many. These drugs can be life-changing, even for those less than two decades into their own.

By Tess Patton

I cried at my gynecologist’s office. I am sure I wasn’t the first and won’t be the last. She started to ask about my birth control prescription and tears welled up in my eyes. She tossed over the tissues.

Snot dripping down my face – a certified ugly crier – I started to tell her that I just didn’t love my body at that moment and that I didn’t know what the root of my problem was. She interrupted my rambling: “Well, is it the weight you’re worried about?” she asked. ”Because we could fix that.”

Fix that?

I didn’t think that was for people like me, a mid-sized girl who was upset she gained the freshman 15, okay maybe 20, and it wasn’t coming off. The sobbing continued and the splotches on my face got splotchier.

Is Ozempic made for me? I didn’t think I was some fitness queen or supermodel, but I never thought I was fat. And just because she thought my parents could afford it meant that I deserved it more than someone with clinical obesity or type 2 diabetes? I didn’t understand.

She had provided me with a clear, simple solution for my crippling body image issues and unrelenting negative self-talk, but at what cost?

Well, at the very least a $1,375 monthly check to my parents and a knock at my ego.

Making of a ‘miracle’?

Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro, Zepound, you may have heard of them?

These drugs are some of the name brand GLP-1 agonists, a class of medications used to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity. But how do these drugs that have taken over social media, celebrity culture and the weight loss industry really work?

The biggest problem that these drugs target is insulin resistance, a defining trait of type 2 diabetes. In much of the ultra processed foods available in the United States, the combination of refined sugars, carbohydrates, trans fats and salt is referred to as the addictive trifecta. These processed foods drive up the addictive pathways in the brain, causing individuals to eat more, get less full and as a result produce less insulin.

GLP-1 medications can revive this insulin production and lower blood sugar levels.

“It’s almost like changing the locks so not as many glucose molecules get into the cell,” Dr. Karla Lester, a board certified pediatrician and now telehealth life and weight coach, said on how the medications lead to weight loss.

According to a 2023 study from the National Library of Medicine, individuals taking these drugs have seen increased weight loss in addition to lowering blood pressure and total cholesterol.

By design these medications are meant to assist those with diabetes; however, the weight loss side effects have attracted consumers, causing these drugs to fly off the pharmaceutical shelves, placing those who really need them in a tricky spot.

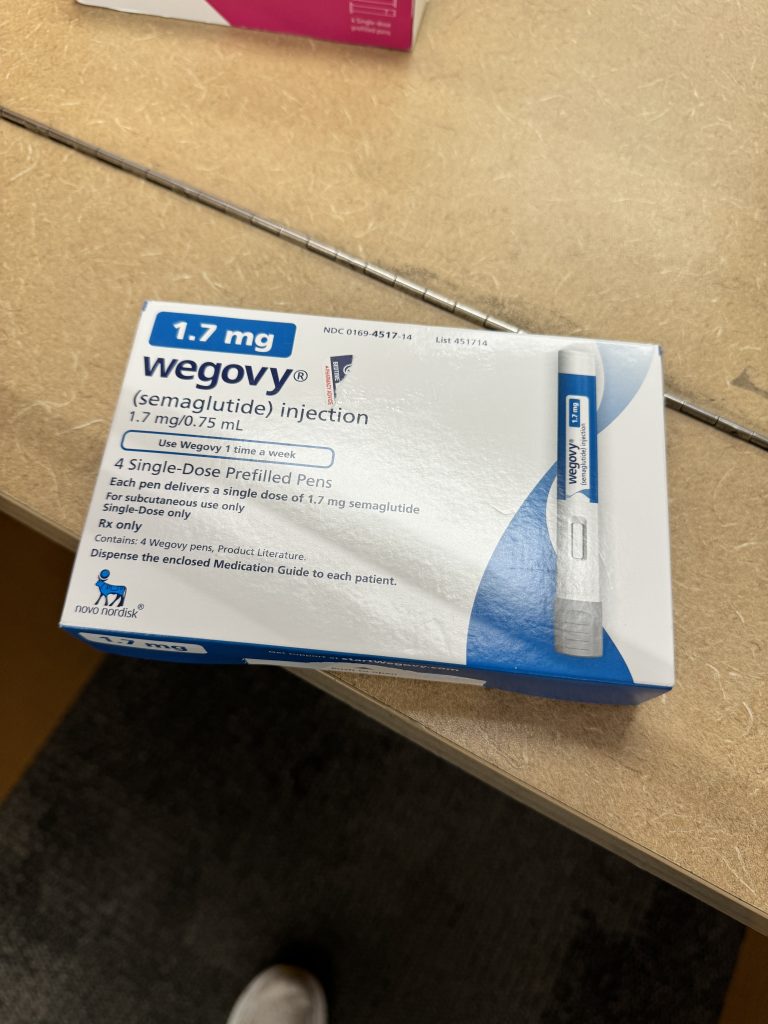

The FDA approved Wegovy, a GLP-1 injectable medication produced by Novo Nordisk, for weight loss for children 12 and up in December of 2022. Shortly thereafter the American Academy of Pediatrics changed their recommendation on how to treat childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity (Photo by Tess Patton).

Rather than their previous “watch and wait” method, the AAP pushed for aggressive intervention, citing childhood obesity as a leading pediatric chronic disease.

For teenagers defeated after countless failed diets and strenuous workout routines, these drugs felt like an answered prayer. The medications quieted the obnoxious, unrelenting “food noise.”

“When a child’s washing their hands, but they can’t reach it. They get a stepstool. The medicine for me is like the stepstool. It’s that little push,” Demi Buckley, a 16-year-old one year into her Wegovy journey, said.

“I didn’t change anything. I’m still eating the same healthy foods and working out and doing sports, and all I added was the medicine, and I finally lost the weight.”

Demi buckley

Eating isn’t easy

For as long as she can remember, Demi’s life revolved around food. Where it would come from next. What snack was going to accompany any activity. Always fueled by the constant need for fullness.

“It was a constant battle because I didn’t like always eating, but I always felt like I had to, especially when I was bored and not doing anything,” she said.

When she was 15 years old, she was almost 200 pounds, entering a zone that doctors deemed “morbidly obese” for her age group, according to her body mass index (BMI).

“The BMI scale is so messed up,” she said jokingly.

This wasn’t for lack of trying. Demi and her mother Deana Buckley both struggled with being overweight, a trait they attribute to genetics. They went on this journey together – everything from keto diets and calorie deficits to motivating each other in the gym. Nothing seemed to work. Demi’s full plate of after school activities, including volleyball, cheer and school band, still didn’t quiet the food noise in her head.

In October of 2022 Deana started the GLP-1 medication Mounjaro weighing in at 366 pounds. The following December the FDA approved Wegovy as a weight loss medication for children ages 12 and up. The weight started to come off quickly for Deana – she lost 100 pounds in the first year. Deana was eager at the opportunity to give her daughter this “miracle drug,” but Demi had her doubts.

“I didn’t think it was gonna work,” she said. “I wasn’t really interested in giving myself shots if it wasn’t going to work.”

Demi would be the first teen patient her family doctor had ever put on the medication, and she had her reservations. The doctor gave Demi the same disheartening eat healthy and work out speech she had heard countless times before. Advice that simply wasn’t making any great changes in Demi’s body.

Demi had reservations of her own. Her eating disorder.

Demi has battled her eating disorder since late elementary school. In sixth grade she had a friend that struggled with her own disordered eating and projected those feelings onto a young Demi.

“She would make me weigh myself when I went to her house, and she would compare jean sizes. I remember one time we went up north to a cabin, and she put on my jeans, but she put both her legs into one [of mine] and was like making jokes about that,” Demi said.

This same friend would tell Demi she couldn’t eat at her house and that she should go on a diet at 12 years old. That’s when she stopped eating. Or tried to.

She would think about food and binge to the point where she needed to purge, leaving her still unhappy with her body and feeling more guilt than before.

“Even with an eating disorder, I still didn’t lose weight. And that’s when I realized that there was an issue with why I couldn’t lose weight, and it was more than just eating,” she said.

She was nervous that starting the drug would perpetuate these thoughts, but with the encouragement from her mom and doctors she took the risk.

Now almost a year since starting the medication in March of 2023, Demi has lost about 60 pounds. The medication has silenced the food noise and shame that she once had around food. Demi did say that the medication has quieted her hunger cues to such an extent that sometimes she doesn’t think about food at all. She credits her mom for supporting her and making sure she gets the nutrients she needs.

“My grades have gotten better, like my mental health is like so much better now that I’m on this medicine,” she said. “I’m confident in my body, which helps me be confident in my mind.”

The kind of progress that both Demi and Deana had was not simply because of the medication. Many doctors have found that access to these semaglutide drugs or GLP-1 receptor agonists combined with nutritional, behavioral therapy helped their patients better manage their hunger and satiety levels.

Demi and Deana pictured on the left pre-Wegovy and on the right one year in for Demi and two years in for Deana (Photos courtesy of Deana Buckley).

Both Demi and her mother have found that people look down upon their use of the drug as an easy way out. She said the most common misconception of people using this medication for weight loss is that they’re just lazy and eating junk food at home. Demi noted that in order for her to see serious changes she prioritized protein intake, behavioral changes and water intake.

“If I really was like eating like crap, like I would have a lot of stomach issues, because this medicine doesn’t mix well with greasy foods and that, and if I wasn’t drinking water working out, then I wouldn’t be losing the weight like I am.”

However, not all patients take to these lifestyle changes easily. Dr. Karla Lester, a self-proclaimed “TikTokdoc” and weight loss specialist, has noticed in her work with children and adolescents that parents’ often well-intended nutritional intervention can give their teens heightened levels of anxiety and body shaming.

Some patients felt like an outcast at their own dinner table, receiving smaller portions than their siblings. Others felt the pressures of diet culture placed on them by their parents.

The TikTok “almond mom” trope came up often in meetings with Dr. Lester and her teens. She said there is a discrepancy between parents wanting to support their kid and how that love and intervention is received. The root of it, she says, comes from self-hatred, body judging and food shaming. Many of her clients are stuck in their own heads so much that the nagging from a parent can be frustrating.

“The parents think they’re helping, but they get in their teen’s lane when they’re eating. They’ll say ‘Are you sure you wanna have seconds? You just ate,’” she said. “It’s just these huge shame triggers.”

Almost all of Dr. Lester’s patients struggle with body image issues before coming into her Zoom room, she said. Her approach to managing her patients’ weight and health is about meeting them where they are and finding a manageable dietary and lifestyle plan.

Not everyone is on board with teenagers using this kind of medication. Deana has been open about her and her daughter’s story on TikTok, opening the two of themselves up to the public. While many express support for the open dialogue, the internet has no lack of haters coming their way – some even threatening to send Deana to Child Protective Services for “killing her daughter”.

“Some of these teens have tried everything. And it hasn’t worked for them. They’ve been so bullied that some of them would rather commit suicide than continuing to try to live their life like this. So you would rather than be dead from suicide than taking a medication that has helped them gain control of their life?” Deana responded.

“Some of them would rather commit suicide than continuing to try to live their life like this. So you would rather than be dead from suicide than taking a medication that has helped them gain control of their life?”

Deana buckley

As Demi enters her junior year of high school, she looks forward to staying involved in cheer volleyball and basketball at school. She also plans to go to community college and get a degree in early education. She credits her newfound confidence and stable mental health to her experience on Wegovy.

“When I was heavier people said something. Now that I’ve lost weight people say something, but I’ve just realized people are gonna say stuff, no matter what I look like. I just have to deal with it,” Demi said. “So I’m happy with where I’m at. I don’t care what they have to say.”

Demi Buckley

Demi is involved in cheer, volleyball and basketball at school. She is also a member of the Business Leaders of America club. She is a rising junior and has been on Wegovy for the past year. She is down almost 60 pounds. (Photo courtesy of Deana Buckley).

Brian Bush

Brian wants to be a professional boxer one day. Ever since starting Wegovy, he has started new hobbies of going to the gym and has reignited his love for the sport he had competed in since fifth grade. Hear more above. (Photo courtesy of Rasheeda Bush).

Kim Carlos

Kim Carlos has been on Mounjaro and calls it a game changer for her life. She just wished she had it earlier. It has affected her relationship to motherhood. Listen for more.

Stopped by a shortage

Brian Bush, an aspiring boxer, actor and real estate agent, is one year into his Wegovy journey. Unfortunately that journey may be coming to an end sooner than he and his mother hoped.

Brian was 370 pounds at age 13.

Like Demi, Brian was encouraged by his mother Rasheeda Bush to take the medication after her positive experience with GLP-1s. Rasheeda started on Ozempic after a recommendation from her doctor in March of 2022. A year into her weight loss goals and 100 pounds lighter, Rasheeda felt comfortable putting her 15-year-old son on the medication.

“If I had experienced severe side effects, he would have never gone on it,” Rasheeda said.

Her only side effects were occasional constipation and dehydration, but nothing severe enough that would prevent her from giving her son an opportunity to change his life.

Brian struggled with weight his entire life. He said the transition from middle to high school, filled with new bullies and mean kids, was not easy. Since he started Wegovy in April 2023, he has lost 45 pounds but has gone down from a 5XL to a XXL.

“I don’t get bullied in school anymore so that’s something new can go into kind of boosting my confidence,” he said.

It hasn’t been the road he imagined. It has been hard to see the numbers on the scale stay relatively the same, but he values little victories — feeling strong in the gym, eating healthier and feeling confident in his clothes.

Brian and Rasheeda have been on this weight loss journey together. After milestones large and small, they are now being forced off of the medication because their insurance does not cover it (Photos courtesy of Rasheeda Bush).

After a full year of growth and progress, Brian is no longer covered by his insurance plan. He will be trying Qsymia, a compounded version of the GLP-1 weight loss medications.

Due to the overwhelming popularity of Wegovy for its use in young adults and its focus on weight loss, its pharmaceutical backing Novo Nordisk has experienced shortages of the drug, meaning people who really need it for aiding in mortality cannot access it. The Danish pharmaceutical powerhouse has invested nearly $11 billion to expand global production capacity, according to Novo Nordisk’s 2023 Annual Report.

Dr. Lester said that many of her clients are waitlisted for the drug by their insurance companies and feel like they are in limbo. Brian falls into this category as well.

His compounded medication Qsymia is a combination of phentermine and topiramate. These two drugs work as appetite suppressants often followed by weight loss results. Rather than an injectable shot like Wegovy, these medications are administered orally.

Brian’s mother, a licensed professional counselor, always has her son’s mental health at top of mind. That is her primary concern as her switches medications..

“One of the major side effects is like, one of the side effects that is a potential is like suicidal ideation,” Rasheeda, a mental health professional, worried. “Brian has reassured me that like, if any of that comes up, he’s going to tell me immediately, but he at least wanted to try it out. Because he wants to keep his progress going.”

“One of the major side effects is like, one of the side effects that is a potential is like suicidal ideation,” Rasheeda, a mental health professional, worried. “Brian has reassured me that like, if any of that comes up, he’s going to tell me immediately, but he at least wanted to try it out. Because he wants to keep his progress going.”

Social media frenzy: information overload?

Social media has changed the way consumers walk into the doctor’s office. The cable television commercials with the sped-up disclaimers are a distant memory for Gen-Z, but influencer culture has changed the game.

Marketing pushes for many of these weight loss drugs have targeted plus-size influencers to give them free access to these drugs in exchange for an endorsement to their following. Companies like Novo Norsdick producing Wegovy and Ozempic and Eli Lilly with a competing drug Mounjaro, testimonies from influencers are invaluable; however, many plus-size creators are hesitant to hop on a trend that is the antithesis of their own brand.

The virality of social media testimony has undoubtedly increased hype around the drugs. NBC reported in July 2023 a surge of more than 4,000 active advertisements on Meta’s platforms. At least three telehealth companies Found Health, MD Exam, and Goglia Nutrition have paid upwards of $6.2 million for deceptive advertisements promoting generic versions of popular weight loss drugs on Meta sites, according to Media Matters – a direct violation of Meta’s unacceptable business practices.

“I’m opposed to all the slick, fresh advertising because consumers think you know more than a physician when they go into a physician’s office or PA’s office. And I go, ‘you don’t know,’” Dr. Clemens said. “All they hear is slick trash. And they have no idea about the consequences, metabolic consequences for you, for that particular person. That’s where the medical professional really has to step in.”

Dr. Roger Clemens, a professor of pharmacy at USC, said that medical professionals and pharmacists have a responsibility to give their clients a fuller picture of life on this kind of medication.

“People expect that they can jump into something really quick and lose that 20 or 30 pounds – and in a very short time – and it doesn’t work. And part of why it doesn’t work is that recidivism is so prominent,” Dr. Clemens said.

For Kim Carlos, a GLP-1 user and content creator, TikTok has built a community that is unbeatable by any. She has garnered over 50 thousand followers on the platform for her candid commentary on life on Mounjaro. Her growth on TikTok has funded her podcast PlusSidez, which dives into similar topics of GLP-1, obesity and more.

However, after recent community guidelines published by TikTok on April 17, Carlos’ following and social media career may be in jeopardy. Weight loss content on TikTok, like suicide, eating disorders and abortion, has been kept under a microscope with some users having to use code names in order to talk about each respective topic.

Carlos has noticed a decline in her views and engagement since the new community guidelines, which crack down on discussions around weight loss supplements and medications.

This form of censorship worries Carlos who has built a living on the platform. She also calls for transparency and community building.

The costs to the mental and physical health of young adults caused by these drugs are under-researched. Many medical professionals, and the FDA panel that approved them, found that the benefits outweighed the risks.

When asked about the long term effects of these drugs on development for adolescents, Dr. Clemens said it’s definitely a risk.

“Those kids, I’m sorry, but they are children in all due respect, right? They’re undergoing tremendous biological changes,” he said. “We have to be very, very careful.”