That’s Judah Maples, an automotive technician and trade school student in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Like many mechanics, Maples’ initial love of turning wrenches on the weekend as a teenager rotated professionally after high school graduation. In the last half decade he’s spent thousands of dollars on tools and parts, hundreds of hours on his 1973 Pontiac LeMans Sport and 1970 Ford Maverick and works part time at a local Chrysler dealership outside of school – all at 19-years-old.

He’s also thought about switching careers.

By the numbers – the importance of automobiles (and mechanics) in America

Maples’ isn’t alone. Statistically, he’s one of the 49% of all American technicians considering leaving the industry according to a 2023 survey by WrenchWay. Current employees and employers point to four primary factors gutting the industry’s backbone: lackluster education, steeper learning curves, lackluster pay and greater health concerns.

Through the next decade, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects an average of 67,700 openings annually for automotive technicians. As of 2023, approximately 676,570 Americans were employed in the field — suggesting a high turnover rate, with many technicians leaving the industry within a decade of starting.

An additional study by nonprofit TechForce found that while the overall workforce grew by 4.3% from 2020 through 2023, the industry will still need another 795,000 technicians by 2027.

Occupational Outlook: 2022-2032

Data provided by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Across the United States, personal vehicles dominate daily commutes. According to Statista Consumer Insights, 73% of Americans use a personal car on a daily basis as a necessity.

Despite being just 4.22% of the global population, the United States buys roughly 18% of all new vehicles with 92% of all households owning at least one and 22.1% owning three or more.

A little under 286 million vehicles were legally registered to drive American streets in 2024, injecting $13.5 billion in direct repair related wages into the economy during the first quarter of last year according to the BLS.

Pumping the Brakes: Trade School.

Like any profession, many aspiring mechanics seek trade school to learn the basics of their industry. But similar to most academic institutions, rapidly evolving developments to the industry means most schools are often years behind the curve.

The options for automotive trade schools are often slim and generally fall in one of two categories:

- Community College: Generally the most accredited option, over 1,000 domestic community colleges offer automotive programs. The vast majority of active automotive technicians were formerly or actively enrolled in one of these programs. Community colleges often strike deals with OEM manufacturers to provide students with newer vehicles and manufacturer training programs, but face other similar vices to other programs the school may offer holistically.

- Private: Private trade schools vary wildly regarding the quality of education and price per semester. Schools like WyoTech and Universal Technical Institute often cost upwards of $45,000 per program, but offer limited credibility.

Both options often suffer from inadequate funding, making it difficult — without subsidies or OEM donation programs — to keep students up to date with the latest technology.

Maples attends De Anza College, a top northern California school benefiting from its close proximity to dozens of Bay Area technological powerhouses. Offered degrees include a hybrid systems program, electric vehicle program and autonomous vehicles program (made possible in partnership with local automotive robotics company Nuro).

But De Anza is an exception, not the norm – a trend current employers are privy to. While many schools may offer hybrid and EV programs, coursework is frequently dated.

“I think that a lot of these trade schools are behind when it comes to teaching the theory to these students,” service advisor Roberto Davila said. “You’re only getting a portion of the theory from the schools, you have to learn the second part of it in the field.”

Modern Demands – Vintage Structure.

Davila has worked in the automotive industry since 2001. Unlike many advisors, Davila began his career as a technician before going to automotive trade school in 2004. He returned to the shop floor until 2011 before taking his first job behind the desk. As the face of the shop, Davila has often been at the forefront of the hiring process for new technicians.

Davila generally attributes the growing labor shortage not to growing lack of manpower, but to a growing lack of talent unable to keep up with modern demands.

“It was either seasoned technicians that wanted to move on to greener pastures, or they were fresh out of school,” Davila said. “The problem with [the kids] was that they didn’t have any real life experience, only had school experience. With the seasoned veterans, their training was so behind the times they were gonna struggle.”

“The technology is changing so fast on these cars,” Davila added. “A lot of it has to do with the electrical systems and the software that’s involved.”

Behind those bundles of wiring and dozens of computers are a slew of now expected features including infotainment systems, blind spot monitors, automatic headlights and stop/start technology.

Those features are also difficult to fix.

“I think about electric vehicles, hybrids, plug-in hybrids, vehicles with cylinder deactivation, vehicles that are turbocharged now,” said Paul Ronney, a Professor of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering at USC. “All these things require not just the mechanical parts that we used to have on traditional vehicles, but also all kinds of sensors and actuators and control systems…[they] now become so tightly coupled that even diagnosing the problems becomes an issue.”

An anecdote Ronney detailed summarized the relationship best.

“I’ve had cheap Jeep Grand Cherokees for a long time, and they had some problem where somehow the parking gear could disengage on the transmission… and it was because some circuit boards could crack. So they came up with a software [patch] rather than replacing that board. Then I read some online stuff – it actually disabled the low range. And if you have a lower set of gears, that if you’re going to go off-road, you need that. So talk about unintended consequences.”

While Ronney believes intricate software work and the day-to-day mechanics have a long way before they cross daily paths substantially, he did affirm “it will do nothing but increase over time.”

“Oh, man, when I started in this industry to now, it’s a night-and-day difference,” said two-decade industry veteran Cody Gabbi.

Gabbi, like Maples, began as a technician straight out of high school. Before starting his own private practice, Gabbi spent 14 years in a standard shop environment.

“When you think you know something about a car, and it may be a 2023 car, just wait till the 2026 comes out. It’s going to be completely different,” he said. “A simple brake job requires scan tools… even for suspension, now they have air shocks where now they have to fill them with nitrogen and go through a whole relearn procedure.”

(Not) Pay Day.

Rapidly evolving technology isn’t the sole driver of the diminishing industry – it’s lousy pay with exuberant out-of-pocket costs.

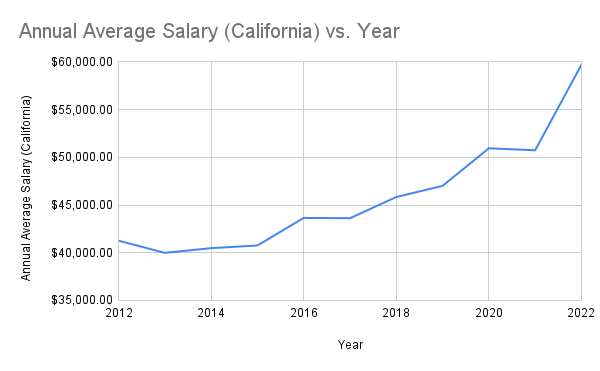

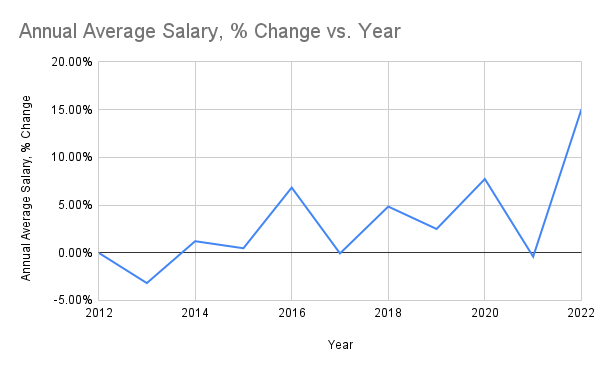

According to ZipRecruiter the average technician in California is paid approximately $27 an hour with a low of minimum wage and a high of mid-40s. Salaries for highly experienced workers can reach well into the six-figure range with overtime and bonus, but that does come with a slew of caveats.

Unlike standard hourly or salaried pay, most technicians are paid a flat-rate salary, or a set price for a job regardless of how long it may take to complete. Intended in incentive mechanics to work harder and save shops money during down periods, increasingly complex repairs have made reaching benchmarked times impossible without years of experience.

“A typical cylinder head job pays I think 17 hours. So you get timed. I have to finish this job in 17 hours, right? And I have to put this car back together to make it look like I never touched it,” Davila said.

It’s a sentiment Gabbi resonates with well – a major driver in his change of work.

“When you’re tearing a dash apart and you’re trying to find a single broken wire, and you may have six hours into it, and they pay you six hours while the guy in the stall next to you could have been doing shocks, brakes and struts and made six hours in two hours worth of work because of flat-rate,” Gabbi said. “I feel that flat-rate needs to go away just because it rewards you for cutting corners.”

Also unlike other lines of work, mechanics are on the hook to provide their own tools. While California shops that don’t provide tools are required to pay double minimum wage, many provide inadequate sockets sets and toolboxes to fulfill the obligation.

Shops, especially dealers, do often provide highly specialized tools including make-and-model-specific scan tools, but employees are often left to fend for themselves for the rest.

Maples, who needs to split his tools between home, work, and school has already spent upwards of five figures in his young career.

During his shop career, Gabbi spent that amount yearly.

“I didn’t like turning any work down, so I probably wasn’t average,” he said.

After founding ‘Cody’s Auto Diagnostics & Programming’, Gabbi now spends upwards of six figures annually to keep up with the latest software.

“There’s always a new special tool coming out to do a special job,” Gabbi said.

“This is one of those industries where you have to invest a massive amount of money in yourself first, and then you’re gonna have to work really hard to start making that money back.” Davila said.

*Wages are measured in the thousands*

Breaking Down.

Snapping bolts isn’t the only thing mechanics need to worry about breaking – it’s themselves.

Leaning over an engine bay, crawling beneath a transmission tunnel, or being wedged under a dashboard for extended periods of time takes its toll on the body.

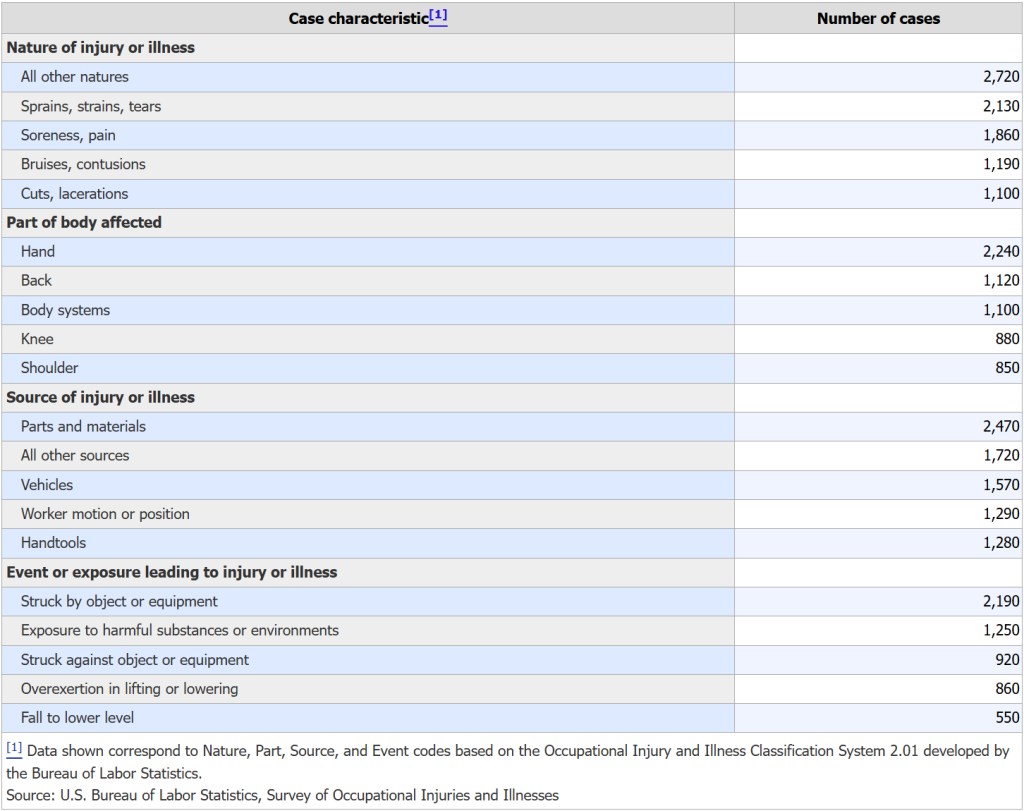

“A lot of the older tech[nicians] at my shop have back issues, knee issues, and I’ve taken their advice,” Maples said. “I’ve gotten a knee pad for doing brakes…I move the rack up with my body…if it’s not a major injury, you just have to push through it.”

Across 2020, 9,940 nonfatal injury and illness cases involving days away were reported to the BLS, producing an incidence rate per 10,000 full-time workers of 185.9. Similar to Maples’ remarks, hand, back and knee issues were noted as being some of the most pervasive in official reporting statistics.

Gabbi also emphasized a lapse in pay as older workers are unable to maintain production as their bodies begins to age.

“It’s one of the only industries that, as you get older, your efficiency slows down because you’re not going to be able to crank out that 20 hours a day of flat-rate work.”

Changing Gears.

Gabbi says the industry is beginning to change with the times as technicians begin to specialize, pointing to himself as proof.

“Shops that try to do anything and everything, they may advertise that, but [customers] may not realize that there are guys behind the scenes, like myself, that actually come in there and help them on those from the programming or those really difficult cars,” Gabbi said.

“It’s not a mechanic anymore,” Gabbi added. “There’s still the shocks and struts and tires, but everything’s going in a whole different direction.”

Others, like Maples, are thinking about new opportunities.

“I’ve been looking into the CHP (California Highway Patrol)”, Maples said. “I love working on cars, but there’s certainly a lot to think about long-term.”

While the industry isn’t going anywhere, it is unclear how soon it will reasonably change. Electric and autonomous vehicles still require the same regular maintenance as any other car in any other driveway regardless of the drivetrain. In the same way the automatic transmission or fuel injection didn’t kill the industry, neither will newer developments.

“The future is software,” Gabbi said. “Anyone denying that should consider looking elsewhere, or start learning.”