As the rise of artificial intelligence continues, so are concerns about its many dangers. Yet when it comes to fashion, AI is also providing avenues into one of the world’s most exclusive industries for those who would otherwise have been barred entrance.

By Maddy Brown

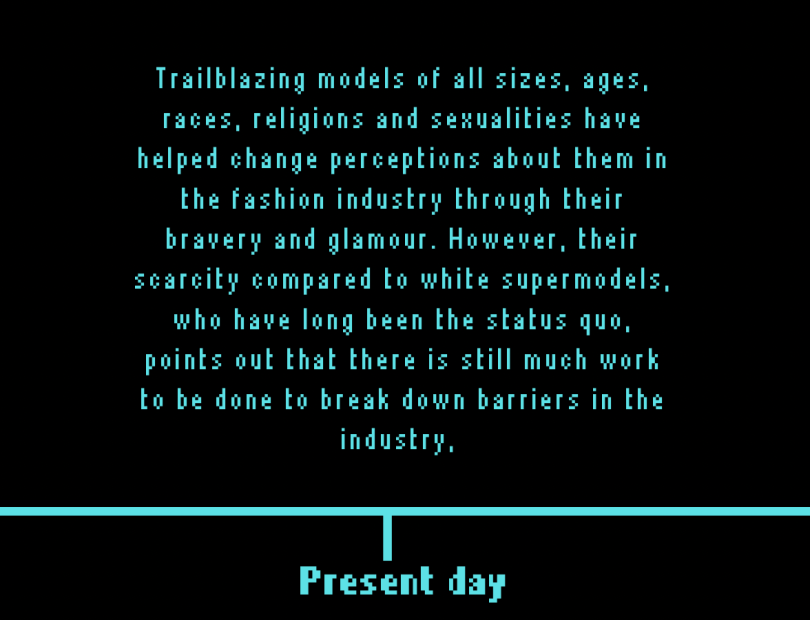

The model has luminous mocha skin. Beneath a full mane of coily hair sit wide, alluring eyes. Her face, composed of dainty features, glows with a youthful flush. She strides confidently forward, long legs and small waist accentuated by the fantastical denim outfit she is garbed in. She’s perfect—because Esther Souto Prego has programmed her to be that way.

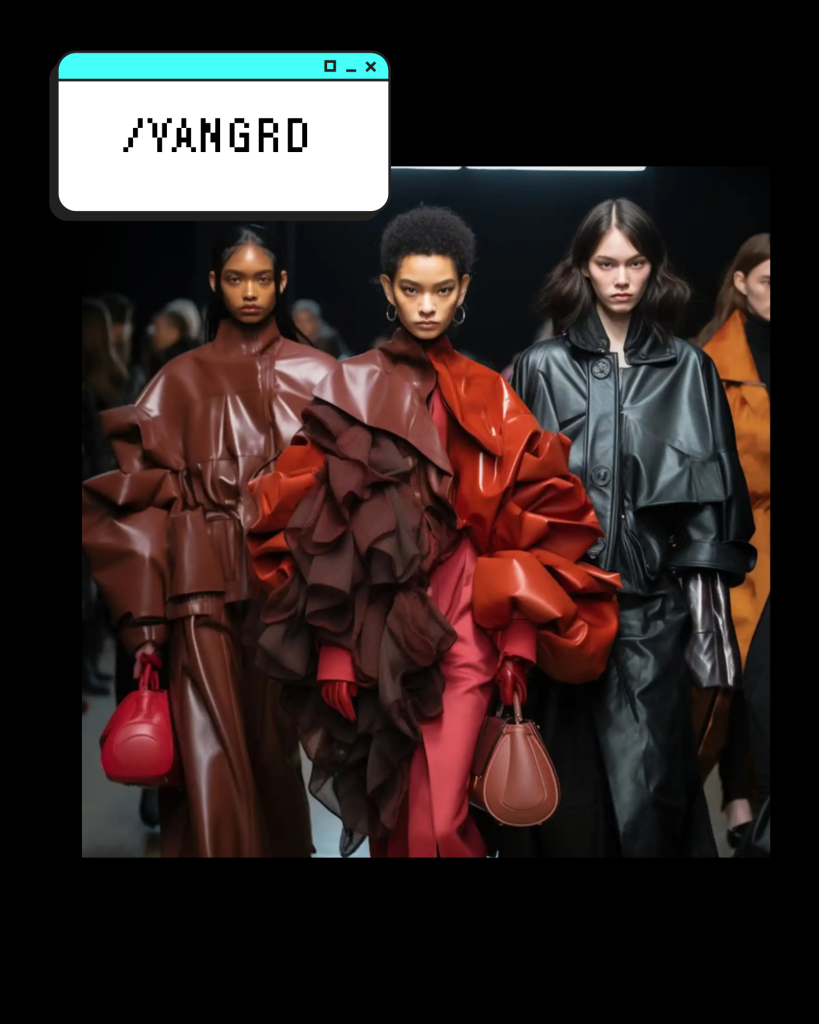

This particular model was one of many the Spanish designer digitally created for the second season of Artificial Intelligence Fashion Week, an entirely digital competition hosted by Maison Meta, a generative artificial intelligence agency. The second season of AIFW, which was held in late 2023, was presided over by fashion industry legends such as Pat McGrath, Tiffany Godoy and Michael Mento.

It was Souto Prego’s exquisitely formed denim collection, accentented with white piping to imitate the Galician ceramics of her home country and named 41 Returns to Sun, that earned her one of the four coveted winning slots in AIFW. The win meant that Souto Prego’s designs—along with fellow winners Tanushri Roy, Magno Montero, and Metamorphix—were turned into physical pieces of clothing that were produced and sold by Revolve.

Her collection wasn’t just inspired by her desire to merge Galicia’s ceramic culture with the future of fashion; it was also a triumphant statement of transformation and renewal that reflected her experience with turning 40 years old in an industry that is not kind to women who dare to age.

“Being a woman and mother in an industry that sees women as “expired” is a challenge,” said Souto Prego. “Even when we have talent and experience, patriarchal biases and ageism still limit opportunities. 41 Returns to Sun is my response to this reality—a statement that knowledge and creativity do not have an expiration date.”

In the 20-plus years she spent in the fashion industry, Souto Prego specialized in production, sustainability, design and styling for the textile and audiovisual industries. Then, like many of her peers in the merged realms of fashion and artificial intelligence, she discovered that AI could be used as a tool “with the potential to transform the sector, reducing waste and accelerating creative processes without compromising quality or essence.”

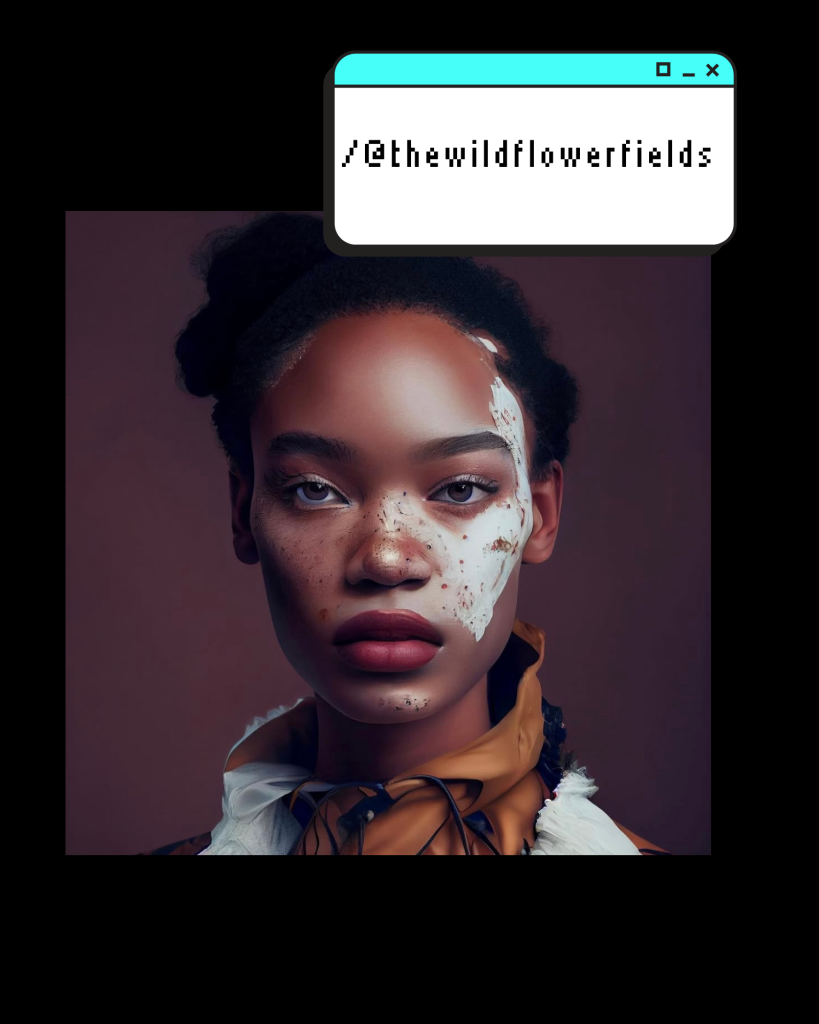

Artificial intelligence might just be the surprise superpower the fashion world needs to truly commit to backing diversity and inclusion on an industry wide scale. As the marketing power of influencers and other online figures with committed fanbases continues to grow, brands are increasingly turning towards them—including fashion designer and crypto artist Wildy Martinez. After a burst of global recognition for an NFT featuring a model with vitiligo—a condition that she shares—that landed her a devoted following, Martinez now works with different brands using artificial intelligence, including collaboration with Dior and L’Oreal last year.

“It’s no longer this high society. It’s not like they’re hiring actors anymore. They’re hiring people who have their own community to launch their products. So I can see why brands are also wanting to use artists to collaborate with different artists,” said Martinez. “I’m a small independent artist, but I think that there’s different companies that want to highlight diversity. They want to highlight creativity, and especially with AI now, they really are looking for these smaller artists.”

As the power of the Hollywood star begins to dim and the appeal of the relatable microcelebrity begins to trend, it’s becoming clearer that a more diverse and inclusive industry is more likely to be shepherded in by individual designers and models or small organizations rather than the large companies and fashion houses who have ruled the fashion industry for decades—and who have so far mostly failed to showcase the kind of diversity that consumers desire and demand.

Others, like creative director and AI artist Carrie Crigler, have had similar revelations. Crigler only started experimenting with AI within the last few years after spending two decades working for a bridal house in New York. With a degree in clothing and textiles from Appalachian State University, a JD from Seton Hall Law School, and two decades of working for a bridal house in New York under her belt, Crigler had only ever really existed in the physical fashion world.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, when Crigler’s job was impacted to the point that she felt creatively “starved,” the AI program MidJourney began to rise in popularity. Crigler was immediately fascinated. After playing around with the new tool, she found that MidJourney, along with other programs that she now uses regularly like ComfyUi, was the perfect solution for her creative slump.

These early fumblings on emerging programs led her to co-found Optikka, an AI-powered design automation company, in 2023. Since its inception, Crigler has worked on everything from optimizing clients’ workflows to computer generated modeling campaigns. Like Souto Prego, she participated in Season 2 of AIFW, which earned her a spot among the top twenty finalists.

“At least in my experience at AI Fashion Week, it was so cool to see participants from literally all over the world enter and just to show off their collections, a lot of which really represented either their culture or their story, or just something that’s not bound by a geographical location and or a budget to produce those garments and to produce that whole story,” said Crigler.

“At least in my experience at AI Fashion Week, it was so cool to see participants from literally all over the world enter and just to show off their collections, a lot of which really represented either their culture or their story, or just something that’s not bound by a geographical location and or a budget to produce those garments and to produce that whole story,” said Crigler.

Artificial intelligence has the potential to make the fashion industry more diverse. Click to hear Carrie Crigler and Wildy Martinez explain how.

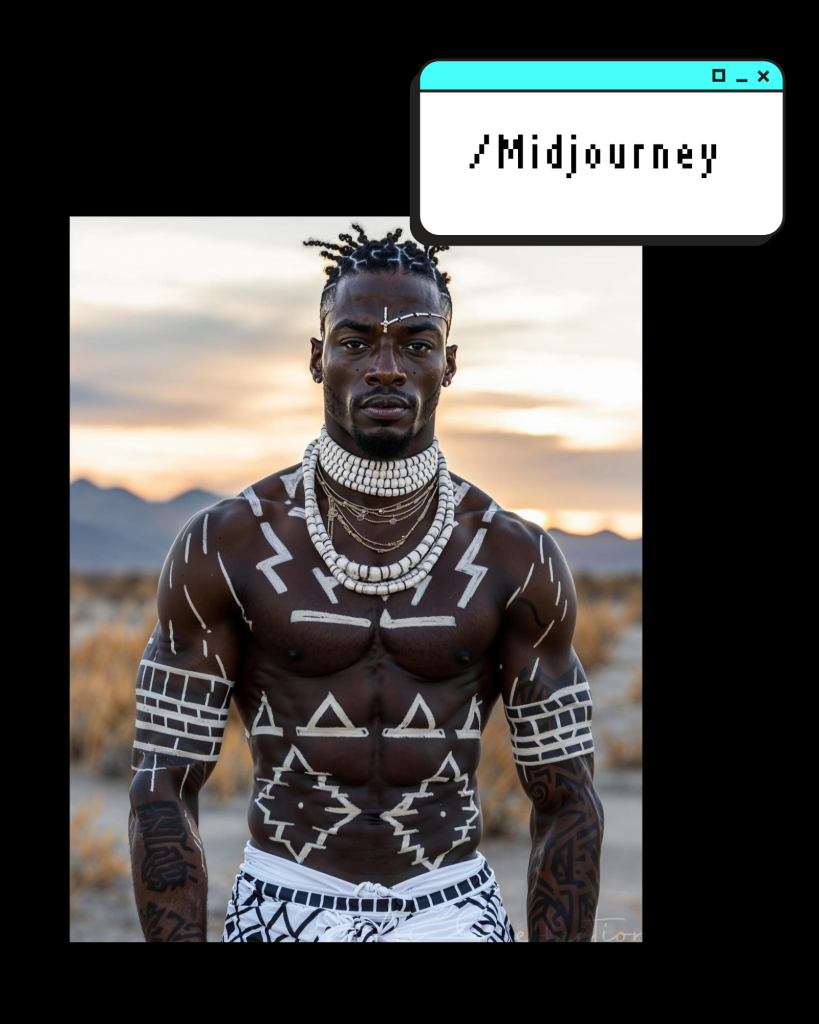

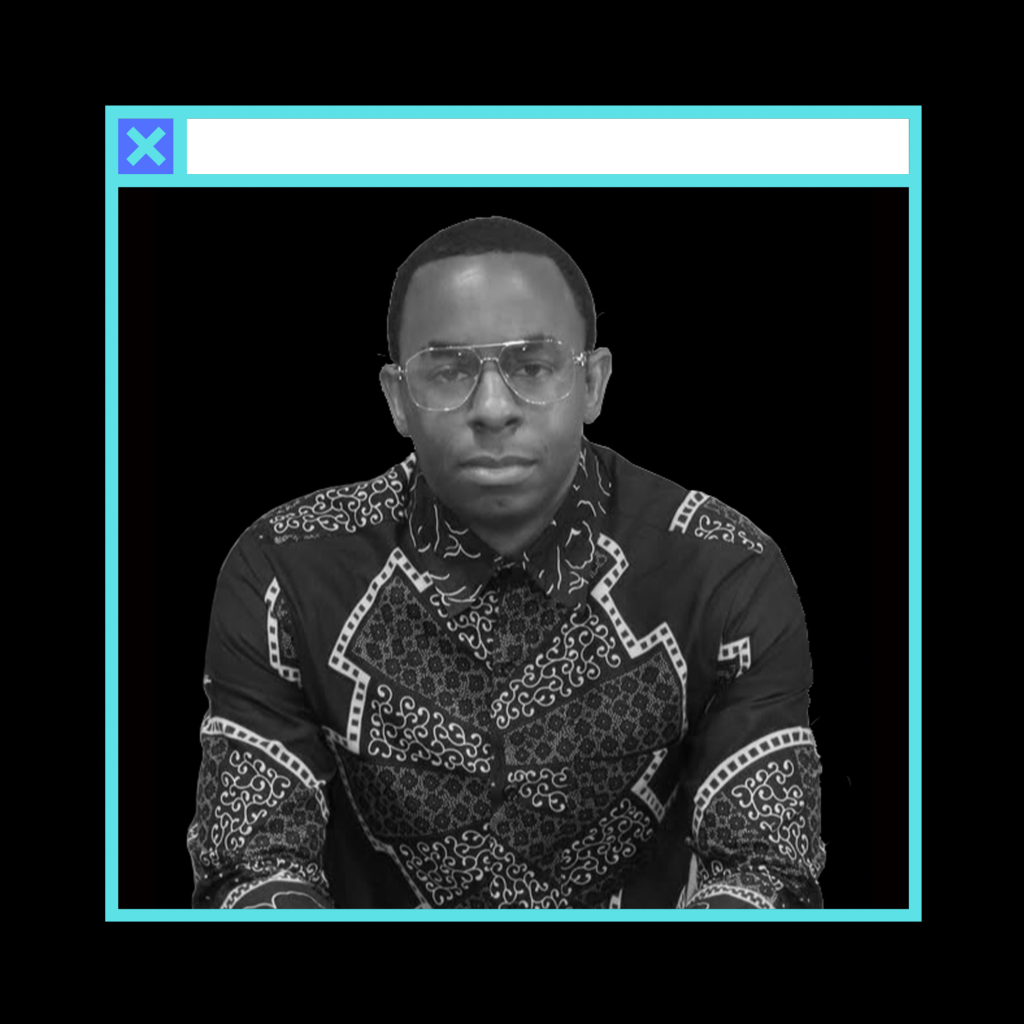

For poeple like Marzuwq Muhammad, who also placed among the 20 finalists from season 2 of AIFW, the ability to create his own designs on models that represent himself is essential. The 36-year-old American software engineer began experimenting with AI as the advent of that technology came about a few years ago.

He describes it as “the latest thing that’s affecting [his] industry in relation to fashion and creativity and using technology in general,” but maintains that his use of AI programs to create models and designs stays in his personal life. Despite his insistence that he has a “career in technology” rather than AI, Muhammad earned himself a spot among the top 20 finalists of the second season of AIFW.

While the garments he dreams up are inspired by his love of geometric designs, Muhammad describes his models as “very Afrocentric.”

“I have people say all the time, ‘Hey, how come all your characters are Black?’” said Muhammad. “Well, grow up as a Black man in this country and not see very many positive images [of yourself] and you’ll understand why I have a desire to create positive images of my own people.”

Wildy Martinez knows firsthand just how badly the masses are clamoring for representation in the fashion industry. Since graduating from the Fashion Institute of Technology in 2006 and continuing to work as a designer, Martinez has been privy to an intimate view of an industry in which the standard of beauty “isn’t really diverse at all.” After being diagnosed with vitiligo right after college, Martinez spent the next decade trying to cover up her skin condition with everything from scarves to makeup.

Then, a few years ago, when Martinez turned 38, she decided that she was tired of hiding and created a fashion NFT titled Wallflower 38, a piece that portrayed a woman with vitiligo. When Wallflower 38 was purchased by a woman with global reach, Martinez’s personal story quickly reached the corners of the world. She started to get messages from people with vitiligo relating to her struggle and from parents of children with vitiligo looking for advice.

“I became one of the first AI fashion designers to represent the vitiligo community, which is something that I have and I advocate for, and my art has it too. And then I just kept on going,” said Martinez.

As a female Afro Latina artist as well, Martinez says she is someone who is “already fighting for diversity the moment [she] wakes up,” simply because of who she is. It’s an especially uphill battle when it comes to depicting vitiligo, which was so underrepresented in AI programs when Martinez first started that they couldn’t even really recognize the condition and would instead generate splotches of white paint. She was forced to train her own AI models—using her own illustrations and pictures and images of model Winnie Harlow—to get accurate depictions of the condition. But, Martinez says, it’s been a “very healing process.”

As a female Afro Latina artist as well, Martinez says she is someone who is “already fighting for diversity the moment [she] wakes up,” simply because of who she is. It’s an especially uphill battle when it comes to depicting vitiligo, which was so underrepresented in AI programs when Martinez first started that they couldn’t even really recognize the condition and would instead generate splotches of white paint. She was forced to train her own AI models—using her own illustrations and pictures and images of model Winnie Harlow—to get accurate depictions of the condition. But, Martinez says, it’s been a “very healing process.”

“Embracing whatever it is that you’ve been insecure about is literally your superpower,” said Martinez. “In the industry, sometimes we’ll see a model that has a gap and that’s the thing that becomes the beauty. It’s just the art of self embrace.”

As it stands, the fashion industry itself would benefit from more diversity, both from an ethical and a financial standpoint. In an article released by the management consulting firm McKinsey & Company, they found “a strong connection between diversity in company leadership and the likelihood of financial outperformance.” According to the studies conducted by the firm, companies in the top quartile for gender diversity are 25 percent more likely to outperform those in the bottom quartile, while companies in the top quartile for ethnic diversity are 36 percent more likely to outperform their less diverse peers.

The Fashion Spot reported that the Spring 2022 Fashion Month boasted the most racially diverse runways of all time—48% of models who walked were people of color—and additional bumps in size, age and gender inclusion. But despite increasingly diverse runways slowly dragging the industry towards a modicum of true representation, the fashion industry is woefully behind when it comes to meaningful inclusion away from the public eye. An inaugural report published by the British Fashion Council in 2024 revealed several key findings regarding the gender and race of those in “Power Roles”—defined as CEO, CFO, Chair and Creative director—in the fashion industry.

The report, which was also produced by The Outsiders Perspective and the Fashion Minority Report in partnership with McKinsey & Company, found that only 9% of executives and boards in the fashion industry in the United Kingdom are held by people of color; and only 39% by women. Additionally, people of color hold 11% of executive team and board “Power Roles,” while 24% are held by women.

The report, which was also produced by The Outsiders Perspective and the Fashion Minority Report in partnership with Mckinsey & Company, found that only 9% of executives and boards in the fashion industry in the United Kingdom are held by people of color; and only 39% by women. Additionally, people of color hold 11% of executive team and board “Power Roles,” while 24% are held by women.

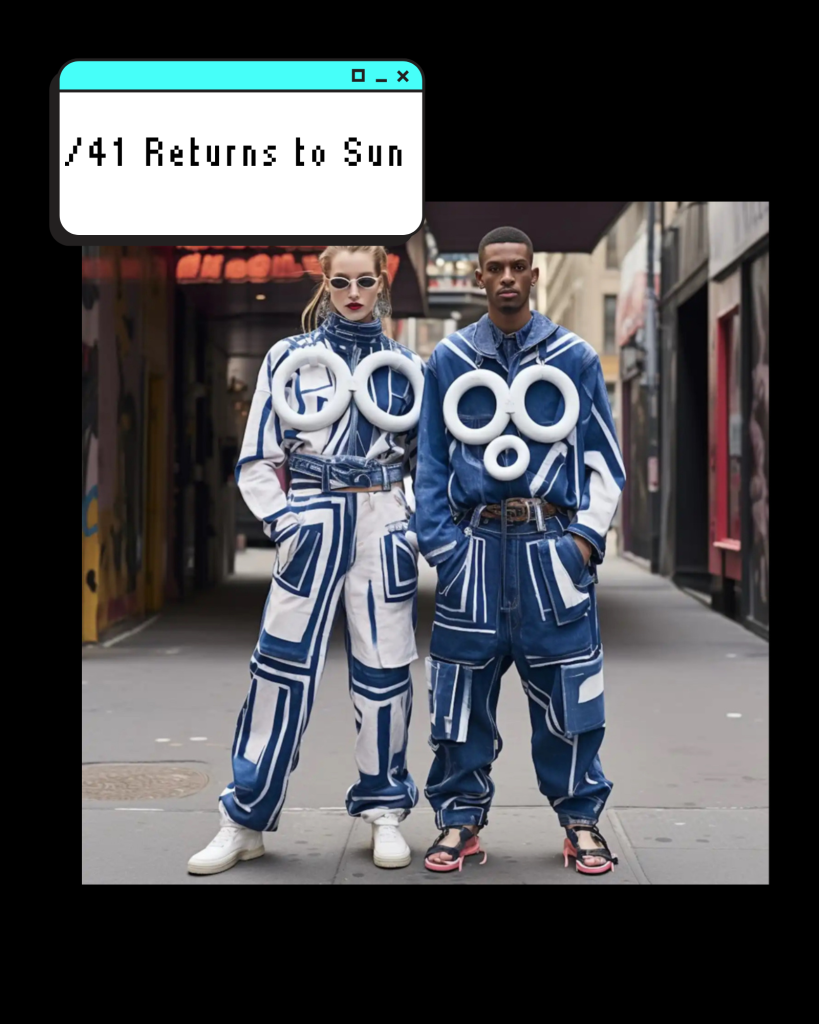

AI modeling is one of the ways in which artificial intelligence has the ability to open doors in the industry that have long been tightly shut, with the lords and ladies of the maisons de couture clutching the keys.

Since launching Optikka, Crigler has licensed real fashion models for a digital campaign her company developed for the Parisian eco luxury brand Thalie. With the models’ permission, her team merged the real facial likenesses of the physical models onto synthetic bodies, which were garbed, accessorized, and posed to the brand’s satisfaction.

At the time Optikka was generating this AI campaign, one of their models was pregnant, which prevented her from being able to book the same type and level of modeling work that she had before. But because the company was only using an image of her face and generating it onto an AI likeness of herself, her pregnancy wasn’t an obstacle to her paycheck.

Crigler is of the opinion that allowing models to sell the right for their likeness to be used in AI campaigns will largely benefit them, despite the danger of deep fakes and other predatory practices. While models in the fashion industry have traditionally had to be represented by a respected agency to get any traction—with the exception of the occasional influencer—now they can take charge of their image and license themselves out.

“I feel like this is a way for true diversity to actually happen, because now you’re empowering people anywhere in the world to license their likeness. They don’t have to actually be living in New York City,” said Crigler. “And, you know, they can also license their likeness in a way that suits them.”

Add in the simple fact that anyone with a computer strong enough to handle AI programs can now create and share designs and models that represent themselves and their communities—or, as Souto Prego calls it, their “unique cultural visions”—and a clearer picture of the potential benefits artificial intelligence can bring to the fashion industry starts to form.

Even individual AI users like Marzuwq Muhammad are dreaming up ways to make generated modeling as fair and inclusive as it can be. Click to hear his plan.

“AI democratises access to design, enabling people from different cultural and social backgrounds to express their creativity without the traditional barriers of the industry,” said Souto Prego. “This is generating an explosion of aesthetic and conceptual diversity in fashion, which is positive because it broadens the visual narrative and challenges established standards.”

However, this new democracy isn’t perfect. According to Souto Prego and other AI designers, not only can AI tools be costly, but some communities lack access to the training or basic digital infrastructure necessary to even begin to use these tools.

There’s more to AI programs than one may think. Click to listen to Jeremy Walder-Willows break it down.

Jeremy Walder-Willows, a London-based photographer and AI strategist, says that some programs cost around $20 to $30 a month, which “adds up” for those seriously interested in producing quality AI images.

Artificial intelligence is a hotly debated topic in most arenas, and the fashion industry is no exception. There are various concerns that stretch beyond the potentially exclusive price tag attached to many AI programs, including questions of ethics and sustainability.

Walder-Willows uses AI programs and watches them impact the world around them every day. From his vantage point as an AI strategist—of which he laments the scarcity—he’s perfectly positioned to see the pros and cons of using artificial intelligence in the fashion industry, most of which exist on a double edged sword. One of his major concerns is that the widespread use of AI to perform simple tasks previously carried out by human workers is already causing—and will continue to cause—mass layoffs on a global scale.

“Your budget is going to get crushed because you don’t need 20 people to do this anymore to meet your deadline. You only need two,” said Walder-Willows. “Now you’ve got half your budget and you’ve got to fire half your team. So that’s one of the big, big issues that’s happening right now, is all these layoffs everywhere.”

Like Walder-Willows and the rest of Crigler’s peers in the realm of AI, which she compares to the Wild West, she understands the paranoia surrounding her industry better than most. For her, that open space can be as exciting as it is suffocating.

“I mean, a lot of people ask me, should I be scared of AI? And yes, we should be in the sense that this is uncharted territory. Where is this headed? How are we going to harness this?” said Crigler. “But I really do believe that…AI is a tool, it’s not talent. Not just anybody can get out there and just come up with something that’s going to then just completely disrupt the entire fashion industry without them having that talent behind it.

Despite the myriad of issues and anxieties that accompany the integration of AI in the fashion industry—and everywhere else—it’s not going anywhere. In response, AI users and designers all have the same thing to say: learn to use it.

“If you’ve lost your job, it’s because you haven’t implemented AI into your toolkit,” said Walder-Willows. “It’s kind of almost your own fault for not doing that.”

Crigler, who like most of her peers is self taught in the art of artificial intelligence, hopes to inspire more people to look at these programs through more than a black and white lens.

“I would encourage any creative to dive in there, to just try to figure some stuff out, see how they can harness this for their own good and to help them,” said Crigler. “Because that’s what AI is for, is to help humans. It’s not to take the place of humans.”

Artificial intelligence is still ultimately an unknown variable, which makes it an object of suspicion for many—but that’s to be expected when one is faced with something wholly unfamiliar and far more vast than oneself. But although it’s littered with its own unique set of flaws and potentially society-altering dangers, when AI is in the right hands, it also has the capability to make meaningful and lasting strides towards true representation in one of the biggest and most exclusive industries in the world.