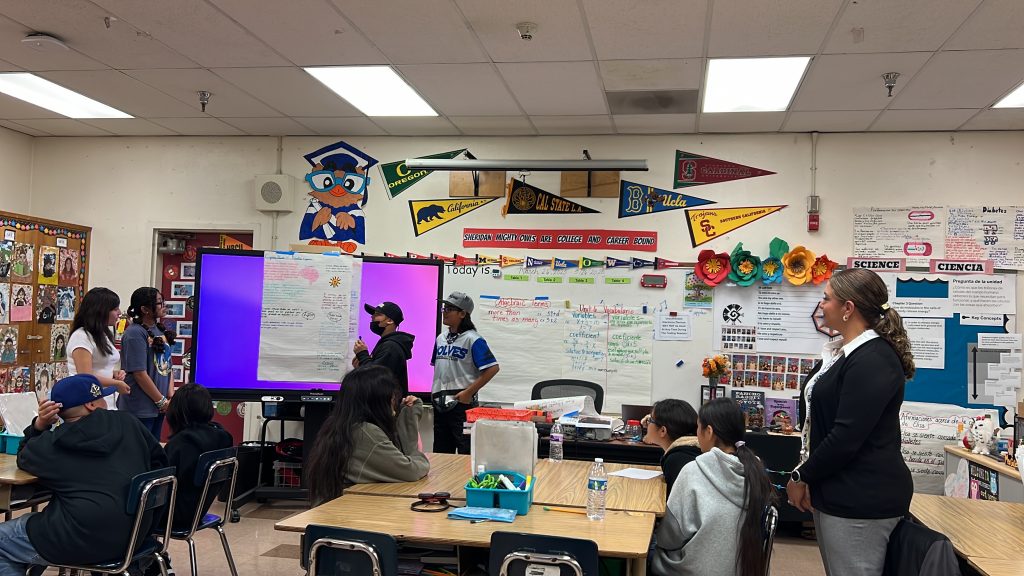

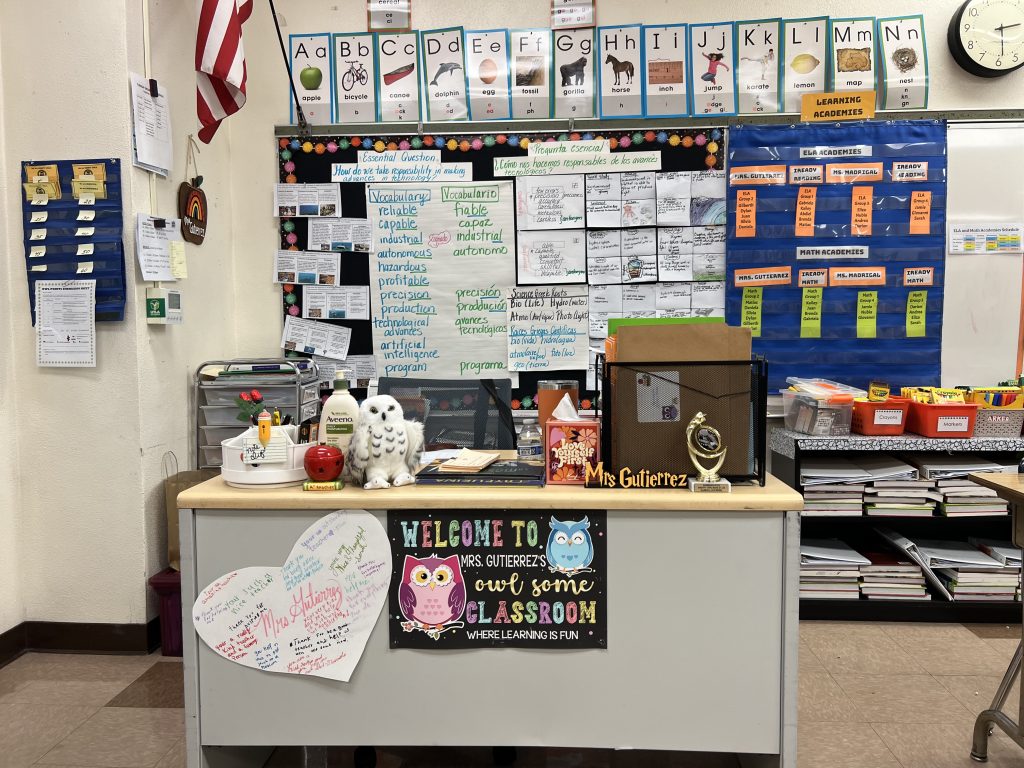

The school bell rings, indicating that it is 2:30 p.m., or the end of the day. Students excitedly gather their belongings and prepare to head home after hours of learning. The classroom is filled with chit-chat as small groups of sixth-graders shuffle out into the hallway. With a big smile on her face, their teacher waves goodbye to her students for the afternoon in both English and Spanish, ready to do it all over again the next day. Gabriela Gutierrez, an LAUSD dual language-certified teacher in Boyle Heights, works tirelessly to give back to new generations in the community that raised her.

“I went into this profession because I grew up in this community,” Gutierrez said. “I feel grounded and I feel that I have to advocate for my community.”

For Gutierrez, ingraining the significance of being bilingual in her students is equal to giving them a superpower.

“Being bilingual is a privilege. It is the way that they can connect with their family, community and culture. And it is their right,” Gutierrez said.

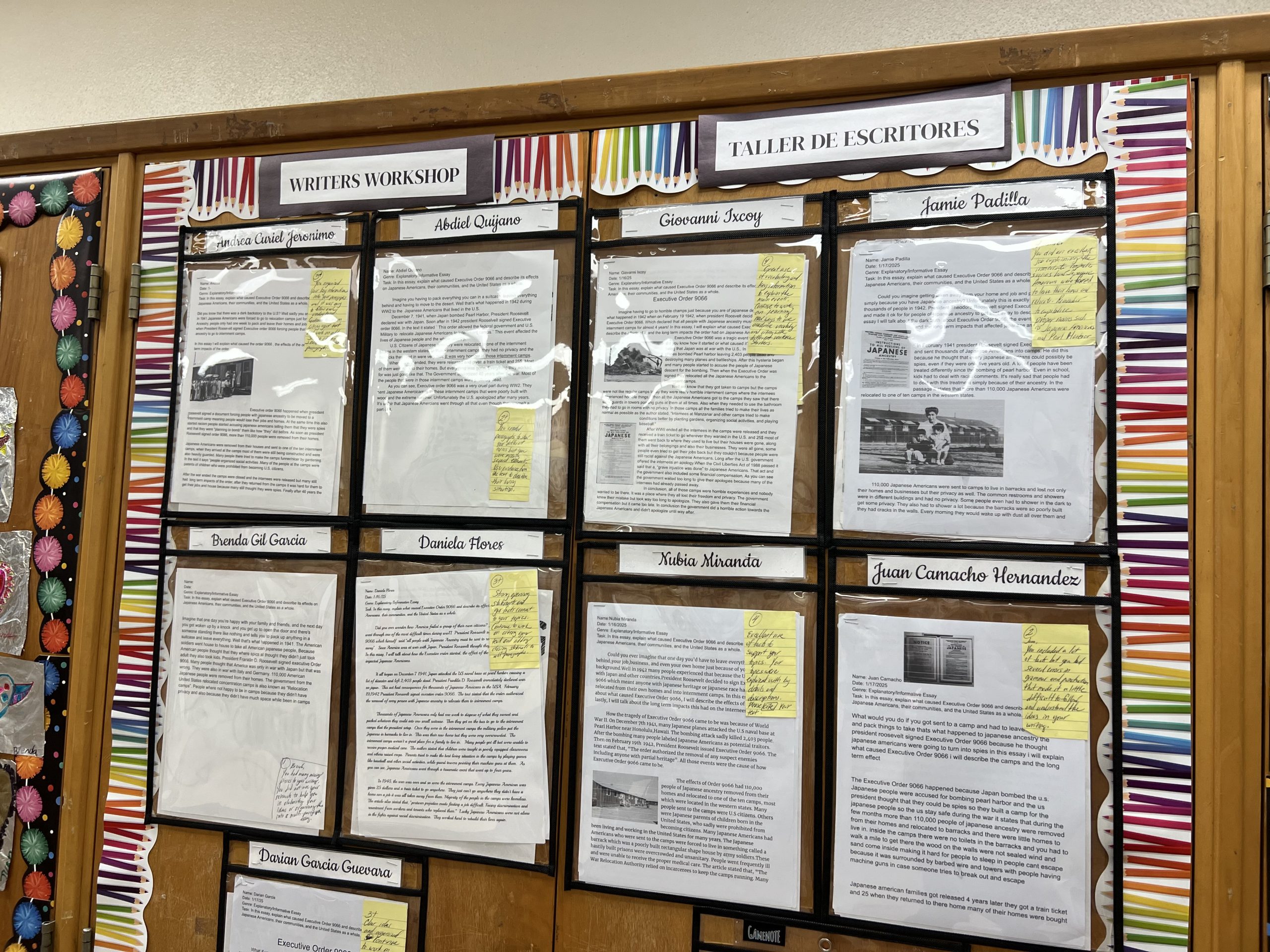

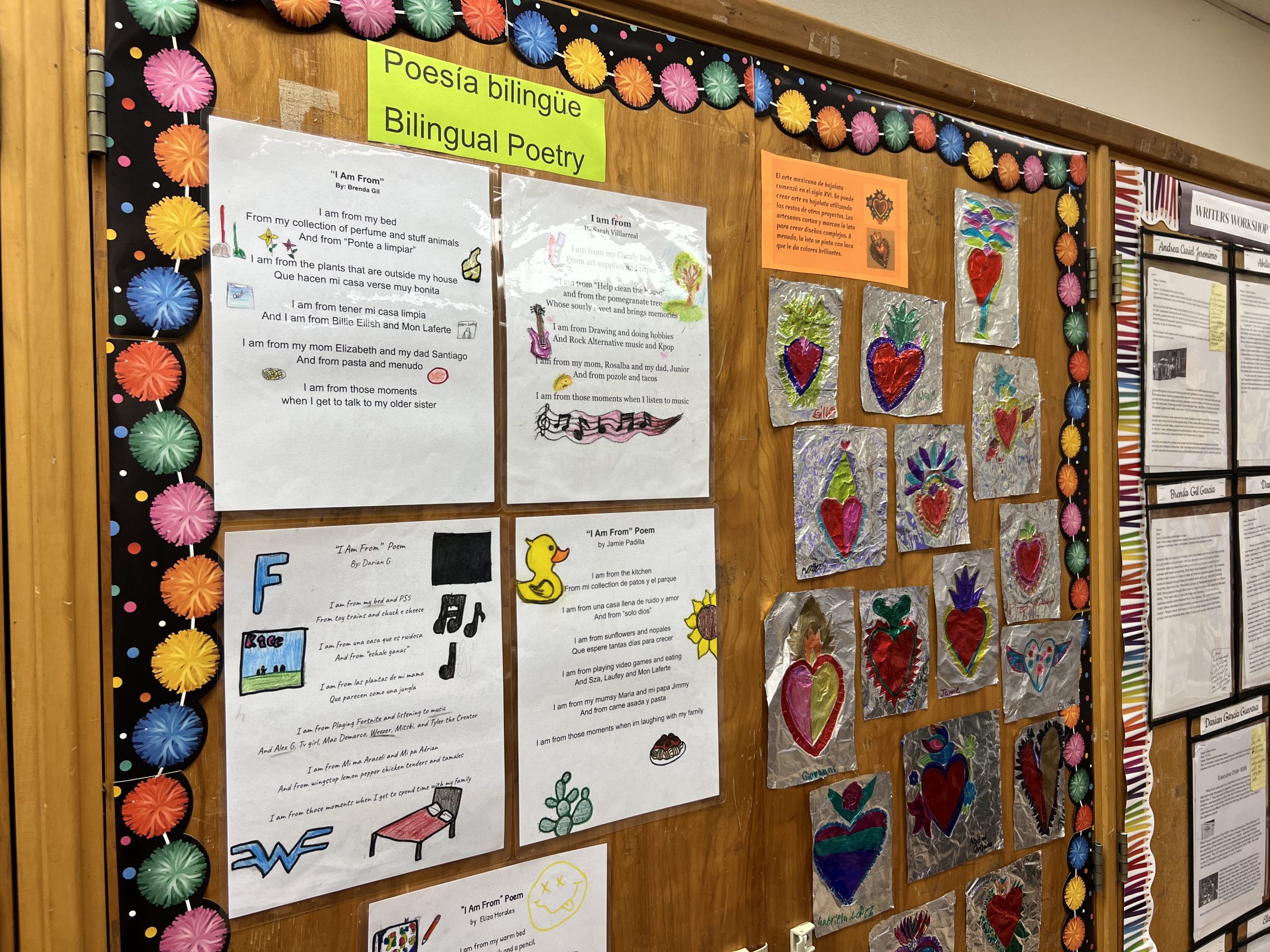

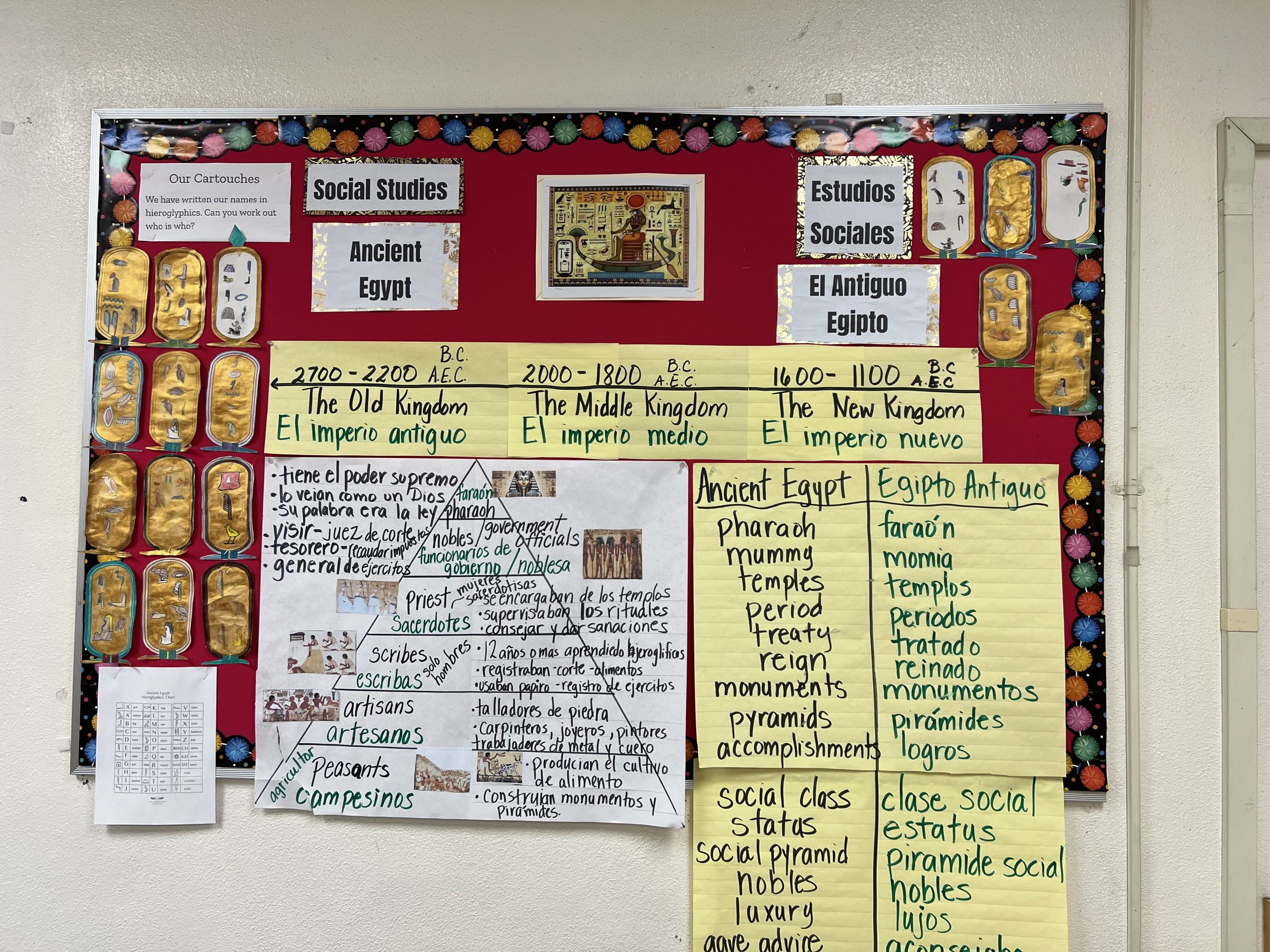

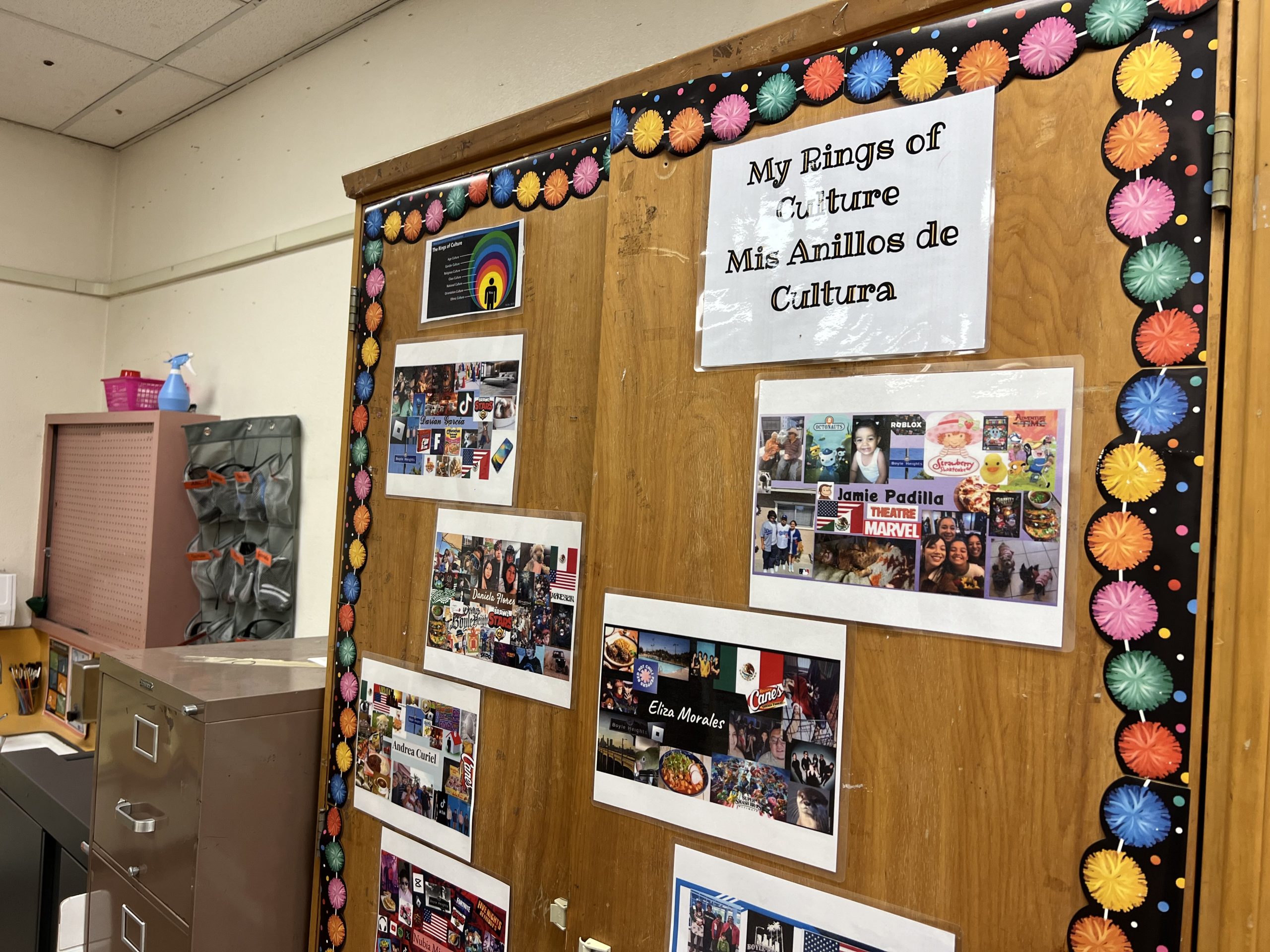

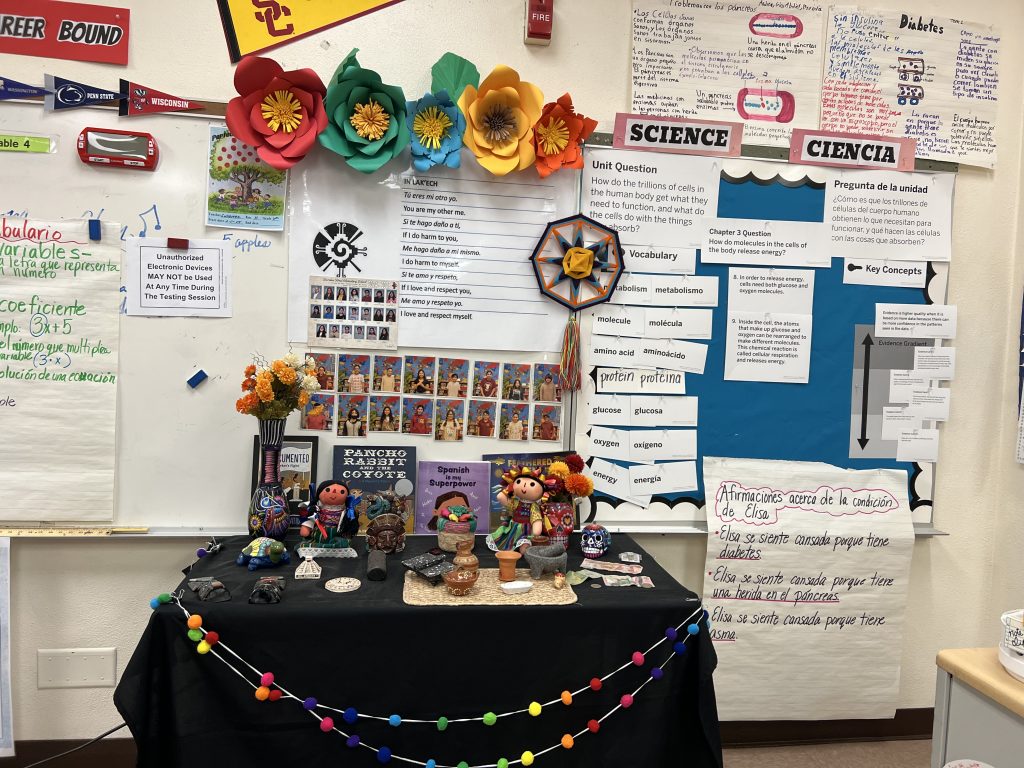

Two years ago, Gutierrez went back to school at Cal State LA to obtain her dual language teacher certification. Now, her English and Spanish classroom is home to Sheridan St. Elementary’s sixth-grade class, the school’s inaugural bilingual class. Gutierrez emphasized that she wants her students to not only be bilingual but also biliterate. Furthermore, she encourages her students to understand the historical, cultural and social factors that come with being bilingual and bicultural.

“The dual language program is based on three pillars: Bilingualism and biliteracy, high academic achievement, and social and cultural competence.”

– Gabriela Gutierrez

Meet Gabriela Gutierrez and step into her classroom

Yet in a school where about 98 percent of kids are Latinx and many come from bilingual households, her class only has 17 students. This causes one to wonder, in a predominantly Latinx community, why is there low enrollment in dual language programs? Why do many immigrant parents hesitate to help their children learn both English and Spanish when it could greatly benefit their kids and families?

“There’s a few different beliefs that are packed in there. One is that a normal person cannot be equally fluent in two languages. That’s one belief. One could see how that would come about. I think partly because there’s so much pressure for immigrants to lose their language here in the U.S. that it’s very rare to meet people who really have maintained both,” UCLA Professor of Linguistic Anthropology Dr. Norma Mendoza-Denton, said.

Real photo courtesy of Norma Mendoza-Denton, image quality enhanced by AI.

Here, factors such as immigration and assimilation become more apparent in bilingual education spaces. This points to a multi-layered, complex picture that goes beyond simply having programs in schools that simultaneously teach two languages. To better understand the causes behind parents’ hesitation that remains today, one must look back into history to uncover the root of the issue. Today, California is one of the country’s leading states in dual language education initiatives, paving the way for other states to expand their education offerings to align with our increasingly globalized society. However, bilingual education has not always been this widely accepted by residents of the Golden State.

Only 30 years ago, California banned bilingual education

First came California’s bilingual education ban in 1998 brought by Proposition 227, a law that made it harder for public schools to provide bilingual education. Essentially, support and resources for dual language programs were removed for 18 years to prioritize English-only initiatives. It wasn’t until 2016––yes, you read that right––just nine years ago when the Proposition 227 ban was repealed after Latinx educators pushed for reinstating dual language education. As a result, a new proposal, Proposition 58, appeared on the ballot stating that schools would no longer be limited to teaching English learners in English-only programs. Parents no longer had to sign a waiver for their child to enroll in dual language classes. Alternatively, schools could implement a variety of programs, including bilingual ones. This reopened an entirely new set of opportunities for educators, students and their families.

Now, as new research shows that multilingual education is more beneficial than confusing to child development, support and acceptance for these programs are growing. However, with a limited bilingual student-to-teacher pipeline, California schools, educators and policymakers are still recovering from the ban nearly 30 years later. Coming up on the 10-year anniversary of the ban’s repeal, how are dual language programs actually doing today and what challenges do educators continue to face?

In California, 59 percent of children ages zero to five––about 1,689,000 children––are dual language learners, according to a study conducted by the Migration Policy Institute. Dual Language Learners (DLLs) are known as young children with at least one parent who speaks a language aside from English at home. Out of that number, 66 percent of DLL families speak Spanish at home.

“Proposition 227, had the greatest impact on policy on statewide systems that underlie effective bilingual programs,” Dr. Julie Sugarman, Associate Director for Education Policy Research at the Migration Policy Institute, said.

Real photo courtesy of Julie Sugarman, image quality enhanced by AI.

It is important to note that with the 1998 ban, California’s bilingual education programs did not completely disappear. However, it all came down to equal access and support. Although some strong dual language programs remained, many throughout the state suffered––leaving only certain students with access and many without.

“What the state has been trying to do since the repeal of Proposition 227 is to build up that policy level, that capacity, so that it’s not just having bilingual education in a few districts that just happen to be interested in it, but that it’s available to all students,” Dr. Sugarman said.

“The other hesitation is that you can clearly see that the people who control English, or are monolingual in English, have the relative lion’s share of powerful positions in our society. So, who wouldn’t want their kid to have an easier time, a more successful career, a more successful future? We all want that for our children and for each other’s children,” Dr. Mendoza-Denton said.

A small but mighty group, Gutierrez’s students have been learning together since kindergarten as Sheridan St. Elementary’s inaugural dual language class.

Gutierrez explained how schools are constantly adjusting and improving dual language programs as new research emerges.

“Before they used to tell teachers that when it was time for English, the children only spoke English. And when it was time for Spanish, the teachers put up a sign and the kids only could speak Spanish. Everything was very divided,” Gutierrez said. “Studies show that our brains are not split in half… When you think, you’re using all your language repertoire. We’re using English and Spanish at the same time.”

This new movement is known as translanguaging, defined as “the practice of bilinguals accessing different linguistic features or modes of various languages to enhance communication, focusing on speakers’ practices and identities rather than on language structures.” While this idea might sound complex, it dismantles the belief that a monolingual individual is “normal” or “ideal.” Essentially, translanguaging opens up new possibilities for both students and educators. Gutierrez strives to instill this concept in her students and encourages them to use their full language repertoire. For example, the kids might read a scientific text in English and then take that knowledge to complete an assignment in Spanish.

This recent study on California’s Dual Language Learners found that from 2015 to 2019, many dual language students were more likely than non-dual language children––48 percent compared to 29 percent––to live in low-income households. These homes’ annual income is 200 percent below the federal poverty level.

“There’s plenty of immigrants that come and have college degrees, but there is a really large number of parents who are very low educated, eighth grade or fourth grade or lower. So not having literate parents means that those children are not maybe being read to, the parents may not understand exactly how to support their kids through school,” Dr. Sugarman said.

Due to this, many bilingual students and parents face a lack of access to the internet and digital skills. Especially after the pandemic, technological tools are heavily ingrained in learning, putting some students at a great disadvantage if they or their parents are not able to use them.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, from 2015 to 2019, Dual Language Learners represented 77 percent of all California children ages zero to five living in households with no internet access, despite comprising 59 percent of the state’s children in this age group.

“Something that I heard when Proposition 227 was passed. One of the kids said to me, and this kid was mixed, so her mom was white and her dad was Latino. She said, ‘does this mean that one half of me hates the other half of me?’ So devastating for a little kid to have to process that kind of message, right?,” Dr. Mendoza-Denton said.

With a variety of barriers and challenges that advocates in the bilingual education space are still working to navigate and overcome, why are dual language programs so important for LA County and the country as a whole? It comes down to community and recognizing each human being’s value.

Lydia Acosta Stephens, Executive Director of Multilingual & Multicultural Education at Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), points to a recent rise in demand from students and parents for multilingual education.

“They’re saying, I want to take those courses and I want to earn seals of biliteracy in more than two languages. And our teachers do a great job all the way through in honoring that pathway.”

– Lydia Acosta Stephens

Acosta Stephens is proud of LAUSD’s reformed dual language programs aiming to better serve children and their families in holistic ways. The educator understands the hesitation and added challenges that many families face in dual language learner households and both she and her team are committed to supporting them however necessary.

“The kids are their tesoros, right? These are their treasures and they’re trying to make sure they provide them with the best program for them to be the best humans and the most success in life. But sometimes people go, ‘well, does this mean they won’t have the English proficiency that they need to have?’,” Acosta Stephens said. “And what we’ve been able to show is they will have proficiency in that target language, that third language or second language and English. They are all on par and equal. Once they start seeing that, once they start seeing the recognition, then teachers and families’ commitment to that work, it grows.”

Real photo courtesy of Lydia Acosta Stephens, image quality enhanced by AI.

“The kids are their tesoros, right? These are their treasures and they’re trying to make sure they provide them with the best program for them to be the best humans and the most success in life. But sometimes people go, ‘well, does this mean they won’t have the English proficiency that they need to have?’,” Acosta Stephens said. “And what we’ve been able to show is they will have proficiency in that target language, that third language or second language and English. They are all on par and equal. Once they start seeing that, once they start seeing the recognition, then teachers and families’ commitment to that work, it grows.”

The LAUSD Executive Director is already seeing a growth in parents’ support for these programs. Acosta Stephens stated that the key is to start instilling these values as early as four or five years old. This year, LAUSD gave out 32,000 bilingual pathway awards to local kids from kindergarten to eighth grade. This shows remarkable progress as in 2017-2018, the district gave out less than a thousand awards. Acosta Stephens explained that this builds momentum and motivation for both students and their families, marking a clear path toward the seal of biliteracy, which students can apply for once they graduate high school.

In 2012, California implemented the country’s first State Seal of Biliteracy Program. Since then, thirty additional states have implemented their Seal of Biliteracies modeled after California’s. According to Californians Together, 60 percent of the U.S. honors high school seniors for their proficiency in English and one or multiple other languages with a seal of biliteracy.

LAUSD offers over 230 dual language education (DLE) programs ranging from kindergarten to 12th grade. Check out this digital interactive map containing all of the dual language schools located in LA County under LAUSD.

As you explore the map below, notice that each color represents a different district in LAUSD’s school system.

Map legend:

- Northwest District (purple)

- Northeast District (blue)

- West District (yellow)

- Central District (green)

- South District (pink)

- East District (brown)

- Click on the red stars to dive deeper into LA County’s history with bilingual education

“One thing that we have found is that when educational institutions acknowledge and recognize the funds of knowledge of the families, the kids do better. The kids do better in school when you recognize that. So I think that that’s one of the keys of multicultural education and bilingual education, is that you’re trying to recognize the funds of knowledge that families themselves are bringing,” Dr. Mendoza-Denton said.

This June, Ms. Gutierrez’s sixth-grade class will graduate from Sheridan St. Elementary as the school’s inaugural dual language class. In a couple of months, the kids who throughout the years have become like brothers and sisters to one another, will spread their wings and head to different middle schools. Yet they will always carry Ms. Gutierrez’s legacy in their hearts and minds as they continue to work toward their seal of biliteracy.

“I know that if I can support my students in being able to speak in both languages and stay connected to their families, I’m already doing a big service to my community,” Gutierrez said. “I am honored to be part of this program and that I get that opportunity to support my students and also help the families.”